Always Wear Earth Tones

Tony Bosco hid in plain sight for more than two decades in the most densely populated state in the nation. How did he do it? And what makes someone exchange all of the comforts of their home for the simplicity of a shed in the woods?

Back toward the end of the summer, I teamed up with a local New Hampshire filmmaker, named Nick Czerula, who was headed down to New Jersey to do a profile of a guy named Tony Bosco.

Tony Bosco hid in plain sight for more than two decades in the most densely populated state in the nation. Exchanging the comforts of his home for the simplicity of a camp in the woods. I heard Tony's story over dinner over three years ago. A story of a woodsman chasing herds deer, on foot, as if he was living hundreds of years ago. I was told he had an intimate knowledge of the woods and area he lived. The punch line or what grabbed me was how moments before the hunt would begin, he would just appear before sunrise, out of the woods, ready. Turned out it was because these were his woods, his camp, his home. After three years of searching I found Tony, this video is his story and why he chose the path less traveled. Film by Nick Czerula | First AC - Ryan Mcbride | Boom operator - Sam Evans Brown | Music: Icelanders - Shimmer | Dustin Lau - We'll Leave Our Names Behind | Dustin Lau - A Love Language | Shot on Canon cameras. C300ii S120 powershot

Tony had lived in the woods in central New Jersey for more than twenty years, building secret shelters on private property, and camping just out of view of society.

Tony grew up in Piscataway, New Jersey. And he grew up in a pretty standard New Jersey way. He played football on the state champion team, chased girls, raised hell and got kind of lousy grades. But he also fished and camped and read books, like My Side of the Mountain.

He graduated high school, worked odd-jobs for a number of years and eventually moved to Florida where he drove a limo and worked for AT&T. But after around a decade in the rat-race Tony got fed up.

“You gotta work all the time,” he told us, “Too much work and no play.”

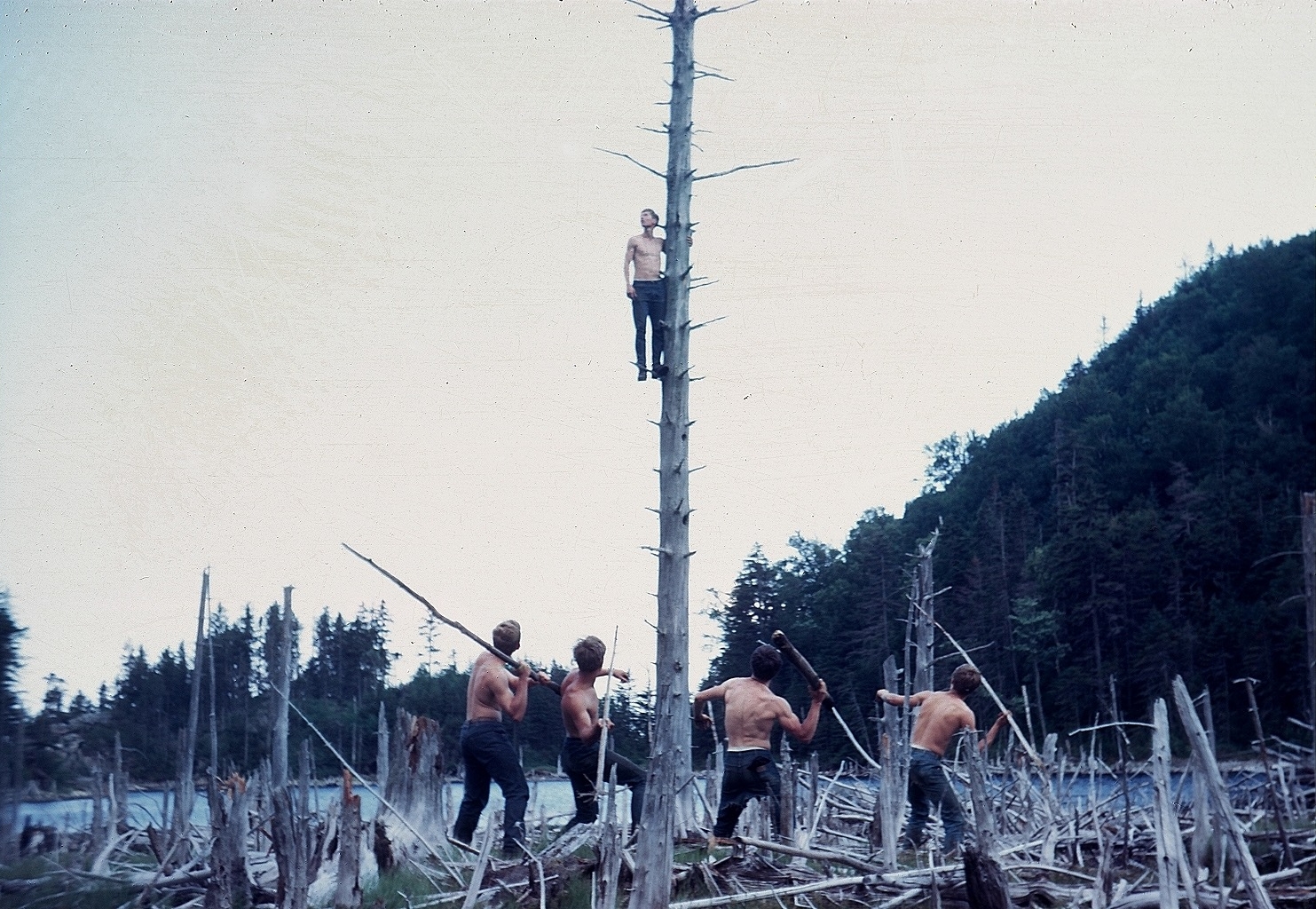

So, Tony moved back home, and just decided to walk away from it all. He walked into the woods. He had many different shelters, scattered about in a lot of spaces on the margins of towns in Middlesex and Somerset counties in New Jersey, but the patch of forest that Tony spent most of his years camping in was a piece of land owned by Rutgers University called Kilmer Woods.

Kilmer woods is about 370 acres. To put that in perspective, if you set up camp in the deepest part of this forest, you’re never more than a quarter mile from a paved road. Tony’s shelter was maybe a couple hundred yards from the nearest apartment building, and just a few hundred feet from the nearest trail.

Maybe you read about the hermit who lived in the woods of central Maine for 27 years, stealing food and supplies from second homes and summer camps that whole time, until he was finally caught. That was a crazy story, but it was also Maine, where there are huge tracts of forest that you can hide out in. This is a tiny island of second growth forest in the middle of a sprawling suburban center.

So, how does someone live un-noticed, on university property for years? Here’s how Tony said he pulled it off.

Seclusion

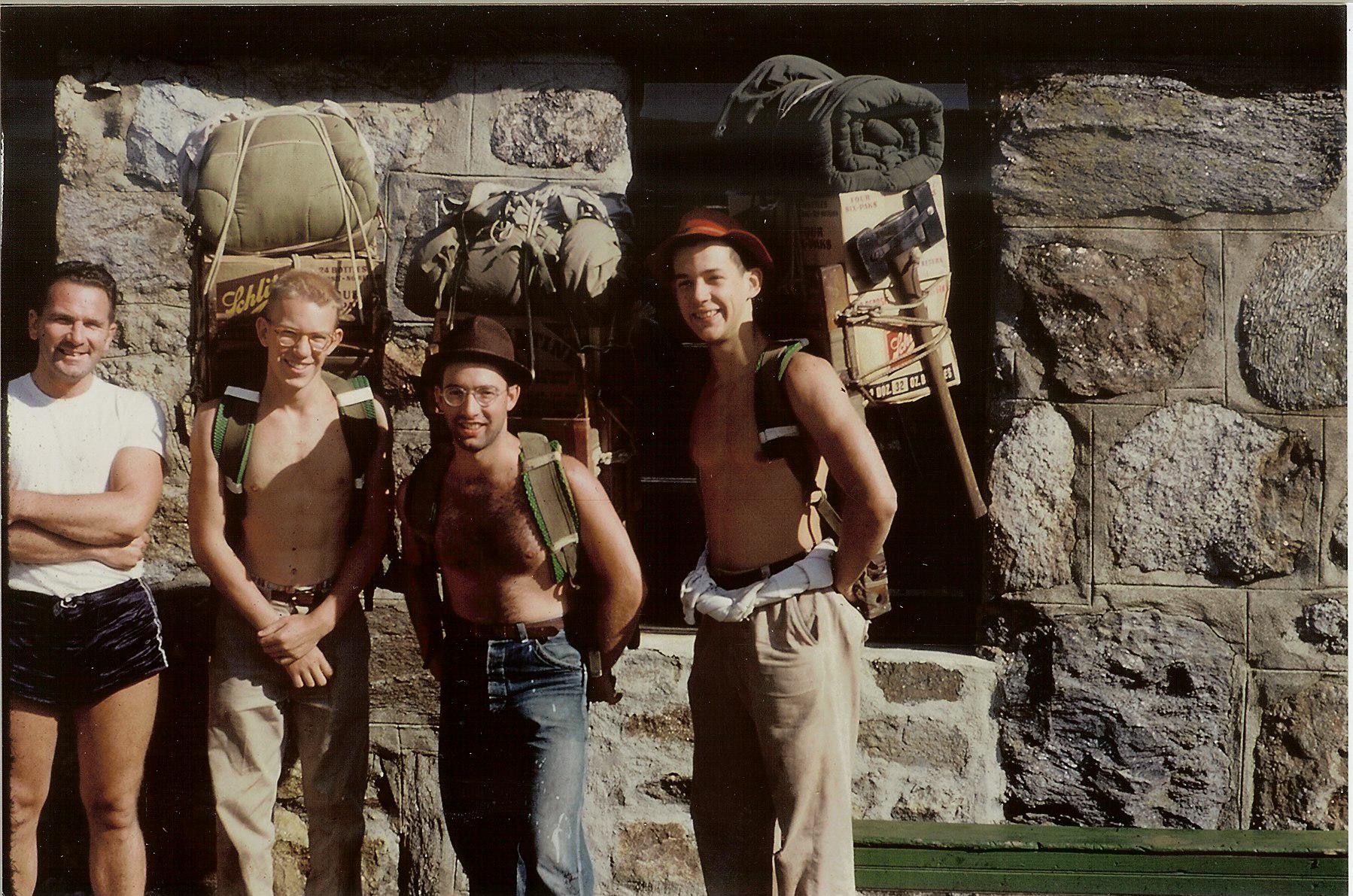

“Don’t put down foot-paths, don’t disturb the foliage, you got to be able to blend, and always wear earth tones,” Tony explains, “Not black, black stands out like white in the woods, you got to wear the earth tones, the browns, the greys, greens.”

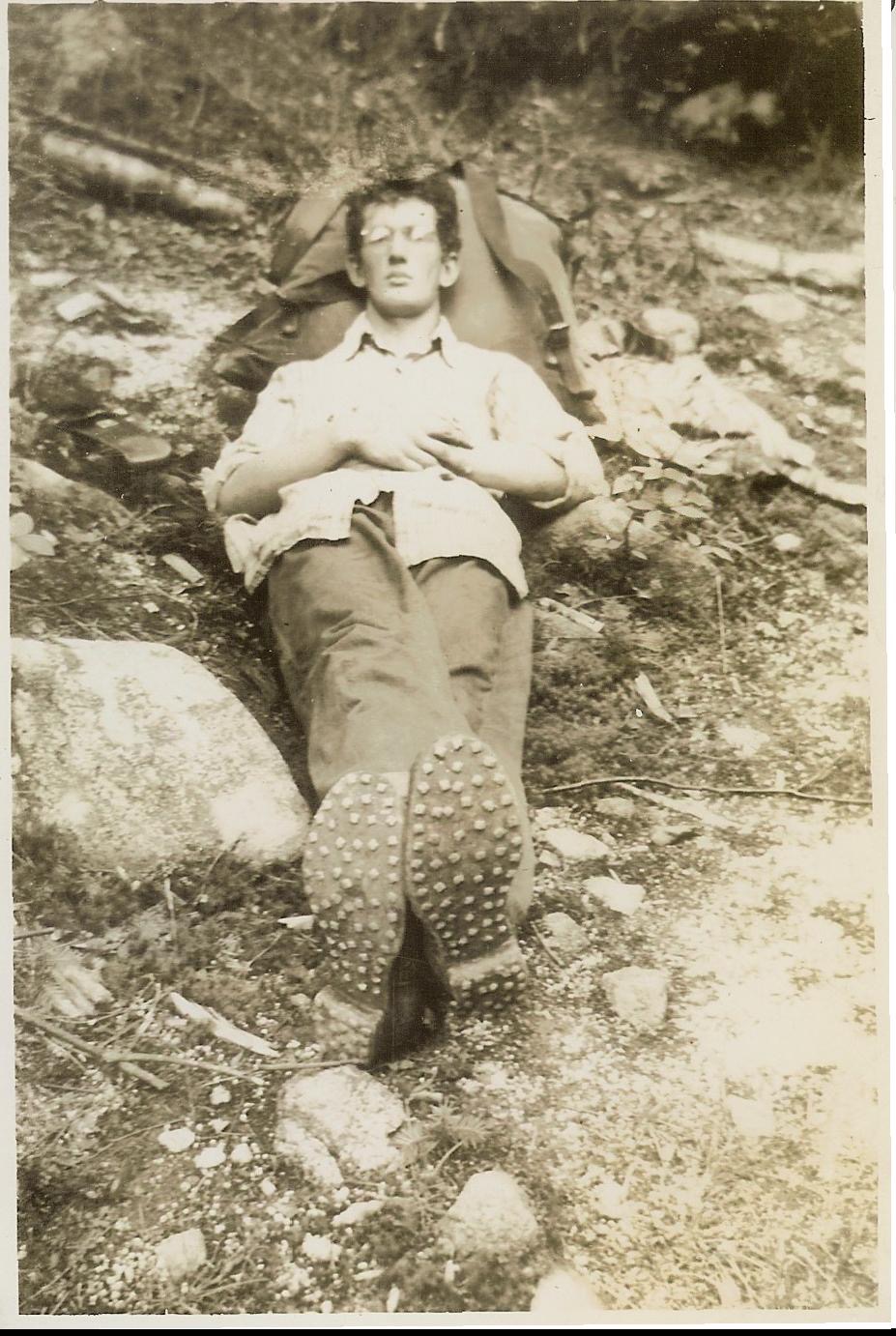

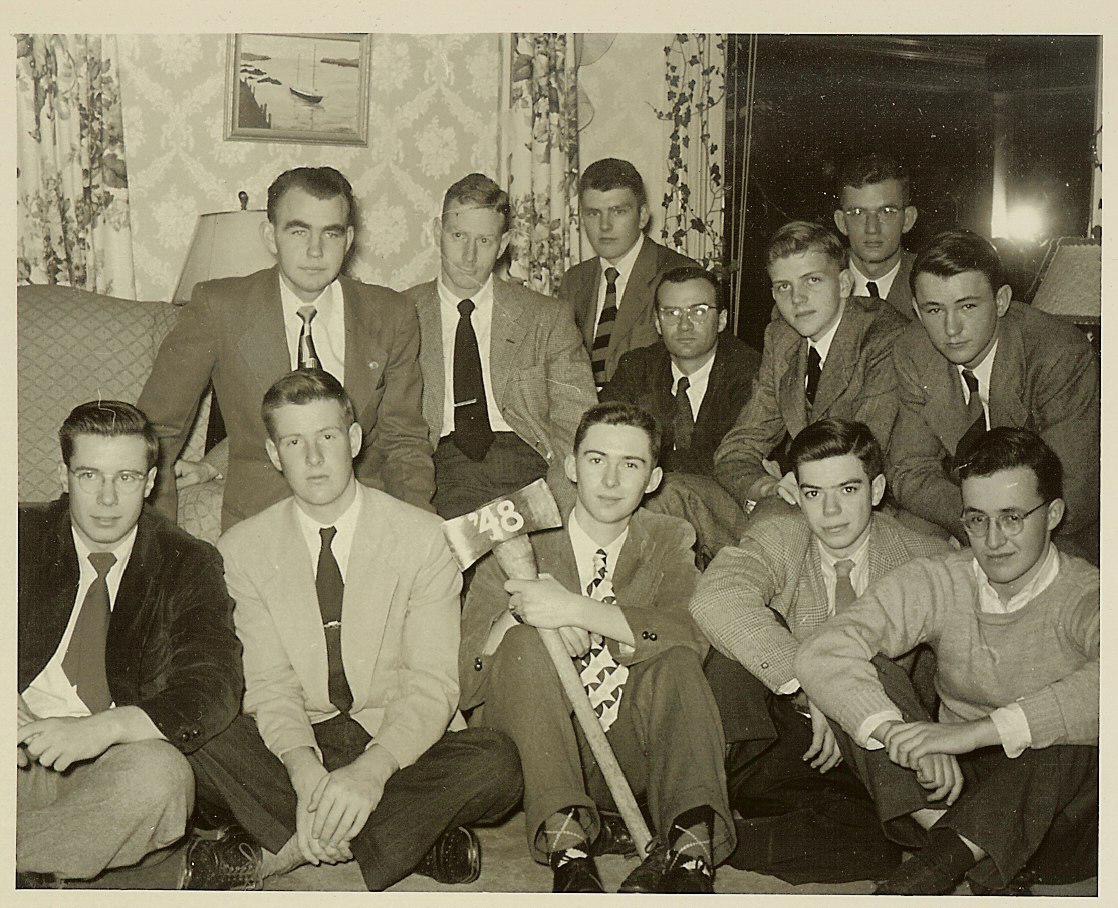

Photo courtesy of Nick Czerula - nickcz.com

Tony’s shelter was tall enough so you can sit up in it, but not stand. That made itharder to spot through the scrub. It had screens to keep the bugs out, windows and doors. It was made of leftover construction materials, and painted to blend in. There were branches and pine-boughs strewn all around it, and it was covered with branches from plastic Christmas trees. The brush in Kilmer woods is thick, and Tony would strategically weave saplings together, arrange dead fallen branches, even haul in old christmas trees that people threw out each year. He would thicken the woods up in certain places to subtly redirect anyone who had decided to leave the trail.

Nick Czerula, who grew up nearby, used to ride his bike through Kilmer woods when he was a kid. “Honestly, my mind is blown because we weren’t only riding there, we were digging there. We were building stuff maybe we shouldn’t like jump trails and stuff. And we never ran into anybody,” he says.

He says when he and Tony met the first time, they had lunch “and I said to him I thought I had almost found him once because I found a deer path or a tunnel, and he laughed, and he said ‘well where’d you end up’ and I said ‘nowhere’ and he said ‘exactly because that’s where I wanted you to end up.’”

Tony calls seclusion “A number 1” in terms of the most important priority for someone who is sleeping outdoors on property they don’t have permission to use “so you don’t have to count on people being honest.”

Keep Clean

Photo courtesy of Nick Czerula - nickcz.com

Tony’s camp was right near a little brook, which he would wash off in year round.

“I would wash every single night, icicles come off my hair, I didn’t care,” he says, “You’ve gotta sleep clean, you’ve gotta stay clean.

This has the obvious benefit of helping him to stay kempt, which helped him to hold jobs, but in speaking to healthcare professionals who work with populations of homeless people, it also helps ward off the dermatological infestations -- scabies, lice, crabs -- that plague people who sleep outside night after night without changing their clothes.

The mantra of keeping clean hold true for your feet as well. Often-times people who are living outdoors will come into a clinic with cases of trenchfoot.

“Rotating your shoes is important, because you want to use them, let them air out, use another pair, let them air out, use another pair… I myself have never had foot issues,” Tony says.

Keep Warm

Tony slept on futon mattresses. (“You get the nice six-inch ones because the nine-inch ones are hard to carry out into the woods.”) His shelters were just wide enough that they could accommodate the futons as long as they folded up on the edges, so when he slept he became “Tony the Hotdog.”

In the winter he found he had to up his calorie intake, because “If you don’t eat enough … 3 o’clock in the morning, your eyes pop open, and you’re freezing.” Tony kept his shelters stocked with provisions from grocery stores (which included many products from Little Debbie, judging by the detritus he showed us), and by hunting deer.

“In New Jersey, you’re allowed, per person, legally, like 100 deer!” he says.

Steer Clear of Trouble

But the truth is, when we get down to it, surviving the elements of a New Jersey winter is not incredibly hard. Even up here in Northern New England there are people who spend the whole winter outside. Generally, it’s not exposure that kills homeless people. “It’s usually a combination of addiction and ignorance,” says Tony, “And there are people who just plain give up. They get to the point of desperation, and they just just plain give up!”

A recent study in Boston found the top cause of death among its homeless population was drug overdose. After that came cancer, mostly lung cancer and liver cancer. (Think smoking and drinking combined with then not going to the doctor for years.) Violence causes some deaths, and doctors say violence is a big cause of injury among their patients.

The kinds of deaths you might associate with survival situations: freezing to death, starvation, dehydration… didn’t even make the list.

So if we ask ourselves, how did Tony survive all of those years sleeping outside… sure his secrecy, his hygiene, his systems for keeping warm and employed, they were important. But most of all he survived because he avoided the worst parts of the human condition: he never grappled with mental illness. He steered clear of addiction.

Tony Lives Inside Now

Eventually, the Rutgers police department found his campsite, and confiscated his stuff, and left him a note that he could come collect it from them. When he did, they charged him with defiant trespassing.

He moved on, found some other camping spots that he would rotate between, but not too much later, about three years ago, he got into a car accident. He was driving his van when he says another car blew through an intersection, leaving him with eleven damaged vertebrae and unable to work. So he had to come inside. These days he’s living with a high school friend, named Joe.

Being in his late fifties, Tony already outlived most people who spend decades sleeping outside.

When you ask Tony what the future holds for him, it’s hard to know what to make of his answer. “There’s absolutely nothing wrong with society. I’m kind of looking forward to growing up one day and joining. I’m getting older now, physically,” he says… but then you can see him check himself and reconsider, “I don’t feel like it’s time... but I’ll move back out to the woods, and be happy.”

Photo by Ryan McBride for Nick Czerula courtesy of Nick Czerula - nickcz.com

Outside/In was produced this week by:

Sam Evans-Brown with help from Maureen McMurray, Taylor Quimby, Molly Donahue, Jimmy Gutierrez, and Logan Shannon.

Special thanks to Nick Czerula for hooking us up with Tony Bosco. Also we'd like to thank the numerous health care professionals we talked to for this story: Marianne Savarese, Jennifer Chisholm, and Paula Mann with Healthcare for the Homeless of Manchester, and Dave Munson and Travis Bagget with Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program.

If you’ve got a question for our Ask Sam hotline, give us a call! We’re always looking for rabbit holes to dive down into. Leave us a voicemail at: 1-603-223-2448. Don’t forget to leave a number so we can call you back.

Our theme music is by Breakmaster Cylinder.

This week’s episode featured tracks from Blue Dot Sessions, Spinning Merkaba, and Broke for Free. Check out the Free Music Archive for more tracks from these artists.