Millionaires' Hunt Club

A quick note: this episode previously appeared in our podcast feed back in the spring of 2016, as an individual segment in one of our hour-long episodes we produced to air on New Hampshire Public Radio. So you might have already heard it, but…you might not have!

Sam is going to take us all hunting this week. Not hunting for animals, but instead, hunting for the secret of what’s behind that 26-mile fence cutting through the woods of New Hampshire, and why some people want it to stay a secret.

From my very first days as a reporter in New Hampshire, I started to hear about a place hidden up in the woods of New Hampshire. A place full of unfamiliar animals from other places, but fenced off from the rest of the state, and kept quiet. I never heard about it directly — it was always through a guy who knew a guy, who had been inside — but the more I heard about the place, the more unbelievable it seemed.

This massive, private park was called a “millionaires hunt club” and “the most exclusive game preserve in the United States” and yet there were many people I know who had lived their entire lives in this state, but had never heard of it. So what is the secret of what’s behind that 26-mile fence cutting through the woods of New Hampshire, and why do some people work so hard to keep it a mystery?

Helen M. Derry at corbin park central station, courtesy brian meyette.

Officially it’s called the Blue Mountain Forest Association, but everybody who knows about it calls it Corbin Park. (Seemingly shortened from Corbin’s Park… we’ll get to the origin of the name.) It’s near the border with Vermont and it’s huge, though its exact size seems to be something of a mystery. Regardless, at somewhere between 24,000 and 26,000 acres this park is actually bigger than something like 60 percent of New Hampshire towns.

You can find the chain-link fence that encircles the entirety of the park at the end of any number of long rough dirt roads that lead to locked gates. It feels almost like like stumbling across a military base full of UFOs or some similar secret. The fence itself looks sturdy, if slightly weather-worn, and at regular intervals features small signs reprinted hundreds of times, “the enclosed park fence and signs are protected by a special law of this state and any person trespassing herein or in any way violating that law will be prosecuted.”

I got my introduction to the park from a man named Brian Meyette, a retired database administrator, who lives in an off-the-grid home, right next to the fence. “In the fall it’s cool, because you get elk bugling in here,” he said as we walked down his icy driveway, “I actually even came down here once because I could hear one and it sounded like he was bugling just inside the fence.”

Elk, in case you didn’t know, are a Western thing. We don’t have them in New Hampshire. Except on the other side of this fence. And that’s not the only thing that’s over there.

“Any time people come up here to work or anything, they always say, ‘oh did you see the pigs?’ said Brian, laughing. When he says pigs, he’s referring to Eurasian wild boar, imported from Germany into New Hampshire. “And no,” Brian continued, “normally you come down here and it’s just you see a bunch of trees, that’s all you ever see.”

But while you might not see them, there are elk bugling and Eurasian wild boars hustling around behind those fences.

But why?

The trouble with finding the answer to that question is that no one inside of Corbin's Park wants to talk about it. Corbin’s Park is a member’s only club. If you are a reporter, and identify yourself as such, not only do the employees of the park not want to talk to you, but the members don't want to talk to you, the people they have invited as guests don't want to talk to you, even some regular folks in town don't want to talk to you.

Meet Austin Corbin

Basically the only way to talk about Corbin's park today is to start by talking about Corbin's park 100 years ago. The farther back in time I went, the easier it was for me to find people who wanted to talk about this place, which is what brought me to Larry Cote. Cote is a retiree, and chair of the Newport Historical Society, which is where all the historical documents about Corbin’s Park have come to be kept.

“This is our 4th year and you’re the first person who’s asked about it, so I’d say it’s pretty rare that somebody’s got a lot of inquisitive-ism,” Cote told me as we dug through binders full of photos and letters.

Here are the outlines of the history of the park. It starts with a guy named Austin Corbin born in 1827, grandson of the town doctor in Newport, New Hampshire, who left home to go to Harvard as a young man. He then he went to Davenport, Iowa where he fell into real-estate and banking, and became one of the founders of the American banking industry alongside giants like J.P. Morgan.

After making a lot of money in the midwest, he then headed out to New York, where he invested in some swampy property out in an underdeveloped borough: Brooklyn. “He drained the swamp, he tore down the shacks, he built two hotels — the Oriental and the Manhattan — and that’s how Coney Island got started,” said Cote.

But as he was amassing his fortune, part of him just wanted to go back to New Hampshire. So he hired an agent to start buying up farms in the towns around his childhood home. In so doing, he didn’t exactly endear himself to the locals. “There’s people that say he was a robber and all that stuff,” said Cote, who was quick to defend Corbin, saying the farmers got fair prices for their land. Even so, there was even a rhyme that people in Croydon — one of the towns bordering the park — started saying about this time:

“Austin Corbin, grasping soul,

Wants this land from pole to pole.

Croydon people bless your stars,

You’ll find plenty of land on MARS.”

Corbin bought sixty some-odd farms, (again, in New Hampshire, this is the size of an entire town) and he set about building his very own dream game reserve.

“The elk cost him $5,000 dollars. The Moose $1,500, the buffalo $6,000, deer and antelope $1,000, wild boar pigs $1,000 dollars, and then additional other animals were another $5,500,” said Cote as he read from a ledger from the park’s archives. Caribou, reindeer, big-horned sheep, pheasants, Himalayan Mountain goats. The park contained animals from all over the world, like an exotic, cold-weather safari.

But just when the park was really starting to shape up, Austin Corbin and his son decided to take some new horses for a day of fishing and picnics by a nearby lake. His driver hitched some new horses to the buggy, but didn’t give them blinders and when Corbin opened a parasol the horses spooked. The carriage was overturned, and both Corbin and his coachman were killed.

For a few decades, the park was operated by Austin Corbin’s son (charmingly but confusingly also named Austin Corbin) and these are what you might call the ‘Golden Years’ of the park. Famous people like Teddy Roosevelt came to hunt, and a world renowned naturalist takes up residence in the park to make observations and take notes. The park’s buffalo were — at least according to some — instrumental in restoring Bison to the American West.

In the early days, the park was open to the public. Every Wednesday, they were invited in to explore and there was even a winter carnival held there when the townsfolk came in for a deer hunt, ski jumping, a ball, and a banquet.

But after Austin Corbin the senior died, his fortune slowly began to ebb away. Austin Corbin the son can’t quite replicate whatever business magic his dad had, and Cote said that the when Corbin the son died in 1938, he was more or less penniless. That same year, a massive hurricane blew down huge amounts of the fence that kept the park enclosed, and boar and elk escaped in large numbers. The park fell into disrepair, until eventually in 1944 his family gave it up and a group of wealthy hunters took it over.

As time went by, the park dropped further and further from the public eye. Today, most people I talk to who are from New Hampshire have never heard of the place.

These days, whatever’s going on in Corbin’s park, stays in Corbin’s park.

Except for when not everything stays inside.

Hunting around the edges

“Back in 1987 we believe,” Sonny Martin began explaining to me over the phone, before his wife shouted from the background (“Eighty-six!”), “Oh now, my wife corrected me, ‘86.” Martin is the now retired former owner of a hardware store in Lancaster, New Hampshire — some 70 miles north of Corbin’s Park.

“So, somewhere, 1st of November, I was sitting in my tree-stand. It was getting dusky, I always call it next to dark,” said Sonny, falling into the rythms of a story he’s obviously told more than a few times, “Well, the next thing I knew, out comes this wild boar, and he just moves out into the middle of the clearing. He reminded me like a train, the way his legs moving, you know, I’ve always said that. And he just stood there, and does this ‘take your best shot.’”

Martin did take his best shot, and he mounted the head of the boar that he killed that day and for years it hung on the wall behind the register at his hardware store.

gate around corbin park, photo by sam evans-brown

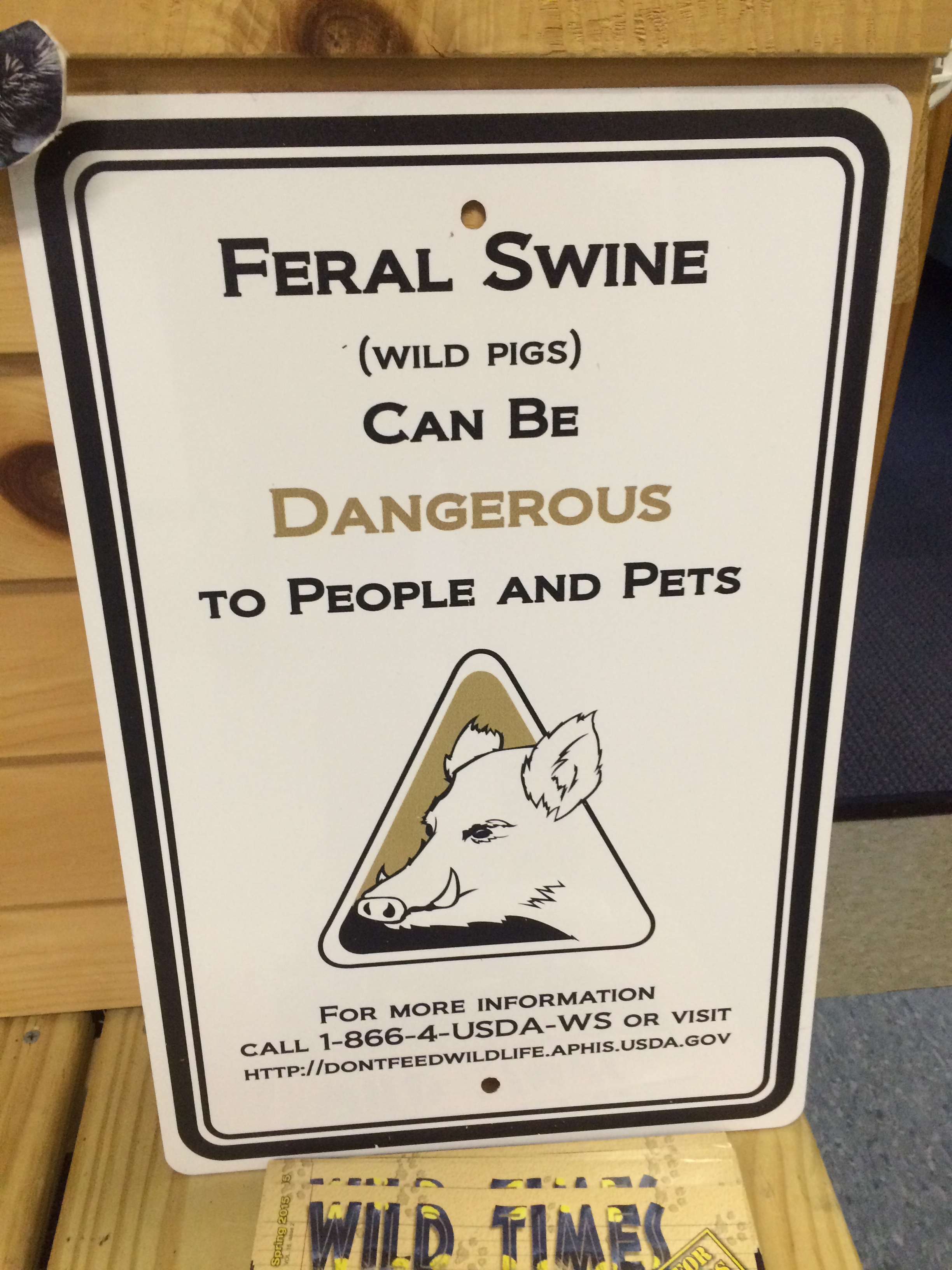

Wild boar can weigh more than 200 pounds, and need to eat more than 4,000 calories a day. They’re aggressive, a nuisance to farmers, and they reproduce like crazy. It’s not unusual for one sow to have six piglets per litter, and sometimes they have two litters per year. To top it all off, they’re smart and wiley. One federal wildlife control official I interviewed said once they design a fence that can hold water, it will be strong enough to hold a pig.

“I mean it was kind of… it was a little bit unbelievable to see something laying there,” Martin said of the animal.

Martin is not the only one to have killed one of the escaped pigs of Corbin park. Technically, the wild boar that escape Corbin’s Park are property of Corbin’s Park, and hunters outside the fence aren’t allowed to shoot them without permission. But the park is liable for any damage to crops or lawns that an escaped boar might cause, so from what I’ve gathered from talking to locals and neighbors, they’re fine with letting local hunters clean up the problem for them. State Fish and Game doesn’t want to issue permits to hunt the pigs because they don’t want to create a demand among hunters for a species that in other parts of the country has become an invasive pest. (Now that you know to look for it, you’ll start to regularly see headlines about men arrested for transporting and releasing wild boar to new places to get new populations going.)

So, with this unregulated hunt, there’s something of a symbiotic relationship going on: local hunters experience the thrill of hunting exotic game without being a part of Corbin’s exclusive club, and they take care of one of the park’s more troublesome issues. I’ve spoken with several people who say they’ve hunted pigs outside the fence, including one who said he shoots multiple ones every year, but none of them agreed to be interviewed in front of a microphone.

It’s another layer of secrets. Not only is what happening inside the fence shrouded in mystery, but some of the activities outside the fence are happening under the radar too. Secrets within secrets: a Russian matryoshka doll of secrets.

But what’s happening today, on the inside?

I tried for a very long-time to talk to someone who is a member of Corbin Park. I called the president of the park. I called the superintendent a bunch of times. I called two other members whose names I managed to find. I even eventually wrote a letter to the park’s general address.

image courtesy brian meyette

No response.

I did succeed in talking to a number of people who have been guests and hunted inside the park and even managed to talk to a current member, but none of these folks wanted to be interviewed in front of a microphone. I was also able to pull the park’s tax returns, because it’s a non-profit, and they file numbers of how many animals are shot each year with Fish and Game.

So here’s what I learned.

There are 30 members. We know who some of these folks are, because their names show up as directors of the park on the tax-forms: one is the CEO of a plastics company that makes things like spout on a can of whipped cream; there’s a self-made millionaire whose company built a stealth boat they’re trying to sell to the US military; there’s the owner of a major gun manufacturing company, who also happens to own Austin Corbin’s old mansion; and there’s even one of the descendents of the Von Trapp Family Singers, from the Sound of Music.

central station, corbin park. image via google maps.

These 30 members and their guests shoot somewhere between 200 and 600 wild boar every year, and between 40 and 120 deer and elk.

From the tax forms you can see that the park makes money off of meat-cutting (members can pay to have their meat butchered for them) but most of their income comes from membership dues, which cost something in the neighborhood of $25,000 dollars a year.

To become a member, you also have to buy the shares of a former member. No one told me how much it cost them to buy into the club initially, but I was told that calling it a millionaire’s hunt club is not an exaggeration.

So why all the secrecy? These are wealthy people who don’t want to attract the attention — and perhaps the resentment — of those who don’t approve of their habits. And believe me, there’s plenty of resentment.

“You can’t get into it. It’s the biggest secret. It’s the millionaires hunt club. The most exclusive game preserve in the United States,” said Rene Cushing in an interview, a New Hampshire state legislator who says that on the political spectrum he leans toward the socialism, “Millionaires only, and New Hampshire peasants need not apply.”

Cushing tried to get a bill passed to require the people who hunt boar inside Corbin Park to buy a New Hampshire hunting license, which is not currently required. I asked him why he felt their exclusivity was a reason to go after the club members.

“I don’t think it’s fair that the people who go surf-casting, pay their $8, pay the Fish and Game Department, should end up subsidizing the Fish and Game Department when they have to go to Corbin Park to respond to a hunter being shot, or when they have to go up to 89 and pick up a wild boar that’s escaped from this fenced in property, and the rest of us are picking up the tab,” said Cushing, “It’s just about fairness.”

I think this is why it’s so hard to talk to members of Corbin Park. The probably feel like just laying out the facts of this place — the cost, the invasive species escaping into the state, the overwhelmingly male membership and guests — will prompt a negative reaction from the Rene Cushing’s of the world.

Reporters sniffing around the fences of the park inevitably puts them into a bind, though. If they talk to reporters, it could encourage more reporters to do more stories, which means more people talking (some negatively) about this gigantic exclusive park. If they don’t talk, then the eventual stories that do come out sound like this one, where the members seem somehow shady, for exercising their right to not comment.

The members probably feel like outside the fence, they can’t win.

So what is Corbin Park?

corbin park central station, photo by sam evans-brown

It’s 26,000 acres of rocky New Hampshire land, fenced off, stocked with elk, eurasian wild boar and white-tailed deer. It’s private, but you can get in if invited by a member, or if you ask on the right day. It was built over 100 years ago, by a super-wealthy banker. Every year, hunters inside shoot somewhere between 200 and 600 wild boar, and between 40 and 120 elk and deer. The animals are fed through the winter to help keep the populations up, but you’re not allowed to hunt around the feeding sites.

Members can get the meat butchered and smoked on site. They can stay in cabins and old farmhouses - the ones that are still standing - that are sprinkled throughout the park. They can hike up Croydon and Grantham peaks, the two tallest mountains in Sullivan County, which are inside the fence.

It’s expensive to be a member, and only 30 people are allowed to be members. When someone wants to sell their shares, you’ve got to know a guy who knows a guy if you want to buy them; there’s no announcement in the papers.

And we also know that most of the people who live near this park, folks like Brian Meyette, have no problem with the place and tend to say it’s a good neighbor. The park is quiet, pays its taxes.

However you feel about all that… it’s up to you.

In the end, I don’t think Corbin Park is actually a mystery. At one point, I spoke to Heidi Murphy a lieutenant with Fish and Game, who has been inside to help the park staff with occasional issues with bears.

“It’s just you know a big huge patch of woods with some hunters that are camping out in some cabin,” she said, laughing at my insistence that it must be more interesting than that.

“It’s, you know, it’s New Hampshire woods,” she shrugged.

Outside/In was produced this week by:

Sam Evans-Brown, with help from Maureen McMurray, Taylor Quimby, Molly Donahue, Jimmy Gutierrez, and Logan Shannon.

Special thanks to David Allaben and Tony Musante from the USDA. By the way, if you see an escaped boar in New Hampshire, you should report it to those guys.

Thanks also to Ken Hoff, who volunteered his time and his skills to give us an airplane ride over Corbin’s Park

This week’s episode featured tracks from [tk tk tk]. Check out the Free Music Archive for more tracks.

Theme music by Breakmaster Cylinder