Powerline, Part III: The Peace of the Braves

Through the '80s and '90s the fight against Hydro-Quebec brought one First Nation rights and prosperity unrivaled in Canada.

Now, on a very different field, another First Nation is looking to adopt their playbook.

The Crees

When they signed the James Bay Northern and Quebec Agreement in 1975, the Crees expected certain provisions from the Quebec government and rights over their traditional territory.

The implementation of the deal, however, fell short of those expectations. Sanitation systems, for example, were lacking enough in some Cree communities to lead to a deadly gastroenteritis outbreak. Education was not up to provincial standards; housing and electricity needed upgrading; emergency response lagged behind the standards of other Quebec municipalities.

Quebec and Canadian governments, the Crees argued, took on responsibility for these issues when they signed the agreement.

A generating station on La Grande in Chisasibi (Jim Deyell Collection, Chisasibi Heritage and Cultural Centre)

So, when Hydro-Quebec announced plans to add another dam to the James Bay complex, the Crees were primed for a fight.

Robert Bourassa, Premier of Quebec, champion of the James Bay mega-project and hydro-power visionary, set his sights on Great Whale. This river is north of the La Grande river, and for thousands of years was used as a highway to Hudson Bay for Crees and Inuit communities. At the mouth of the river are the communities of Kuujjuarapik and Whapmagoostui.

Click and drag to explore the communities around the Great Whale River

While the Crees had ostensibly agreed to the completion of all of the phases of the La Grande complex—including the Great Whale—by the mid-eighties, the indigenous people now had first-hand experience with the after effects of damming.

In the years since the damming of the La Grande, methyl mercury levels had risen in the water, and so risen in the fish and the people who ate them. Hydro-Quebec suggested limiting fish consumption.

The waters of the La Grande, once frozen in winter, now moved too fast for safe crossing by dogsled or snowmobile. On two other Northern rivers where Hydro-Quebec managed the flow, thousands of migrating caribou drowned in the rapids; the Cree blamed Hydro-Quebec.

Drag the arrows to see the James Back watershed and La Grande before and after Hydro-Quebec dammed and flooded the area

Lead by Grand Chief Matthew Coon Come, and partnering with environmental groups across North American, the Crees and Inuit launched a public relations battle against the Great Whale Project. On Earth Day in 1990, they rallied huge crowds and posed with their Odeyak, a canoe-kayak hybrid that they paddled from Northern Quebec to Manhattan.

New York state already purchased some of their electricity from Hydro-Quebec, and signed a contract to purchase even more from the Great Whale. But with everyone from Greenpeace to the Pope in support of the Cree fight, New York Governor Mario Cuomo backed out of the energy deal with Quebec.

The Great Whale project lost footing, and when political control of the province flipped in the next election, it was shelved. The Crees found themselves victors.

This loss would lead to a massive shift in strategy at Hydro-Quebec. The next time the company proposed a project—the Rupert River diversion—they worked with the Crees. And after the whole Cree nation voted in favor of the deal, Hydro-Quebec was permitted to proceed.

But not without another landmark agreement.

They called it "La Paix des Braves." The Peace of the Braves.

Hydro-Quebec would compensate the Cree communities, to the tune of $3.5 billion dollars over a span of 50 years. And the Crees of James Bay would have joint jurisdiction over mining, forestry and hydro-projects on Cree land and territory.

With just nine communities receiving around $70 million a year, some say the Crees of Quebec are now the most prosperous First Nation in Canada.

The Innus

The Peace of the Braves was signed in 2002. Years later, Cree leaders say these deals with Hydro-Quebec were, in many ways, good for their people.

But there are other indigenous people who interact with Hydro-Quebec, and they haven't seen the same results. Decades ago the Pessamit were given a raw deal by the utility, and are now—decades later—giving the Cree playbook a shot.

Click and drag this 360-degree video to explore the Betsiamites

The Pessamit are reaching out to international journalists, trying to tell their story beyond the borders of Quebec. And at the center of that story is the the Betsiamites River, which forms the Southern border of the Pessamit Reservation.

It was dammed by Hydro-Quebec in the late 1950s, and in the '70s the community received a small one-time payout, intended to cover all damages, past and future.

But there are things happening now, the Pessamit say, that Hydro-Quebec is not within their rights to do.

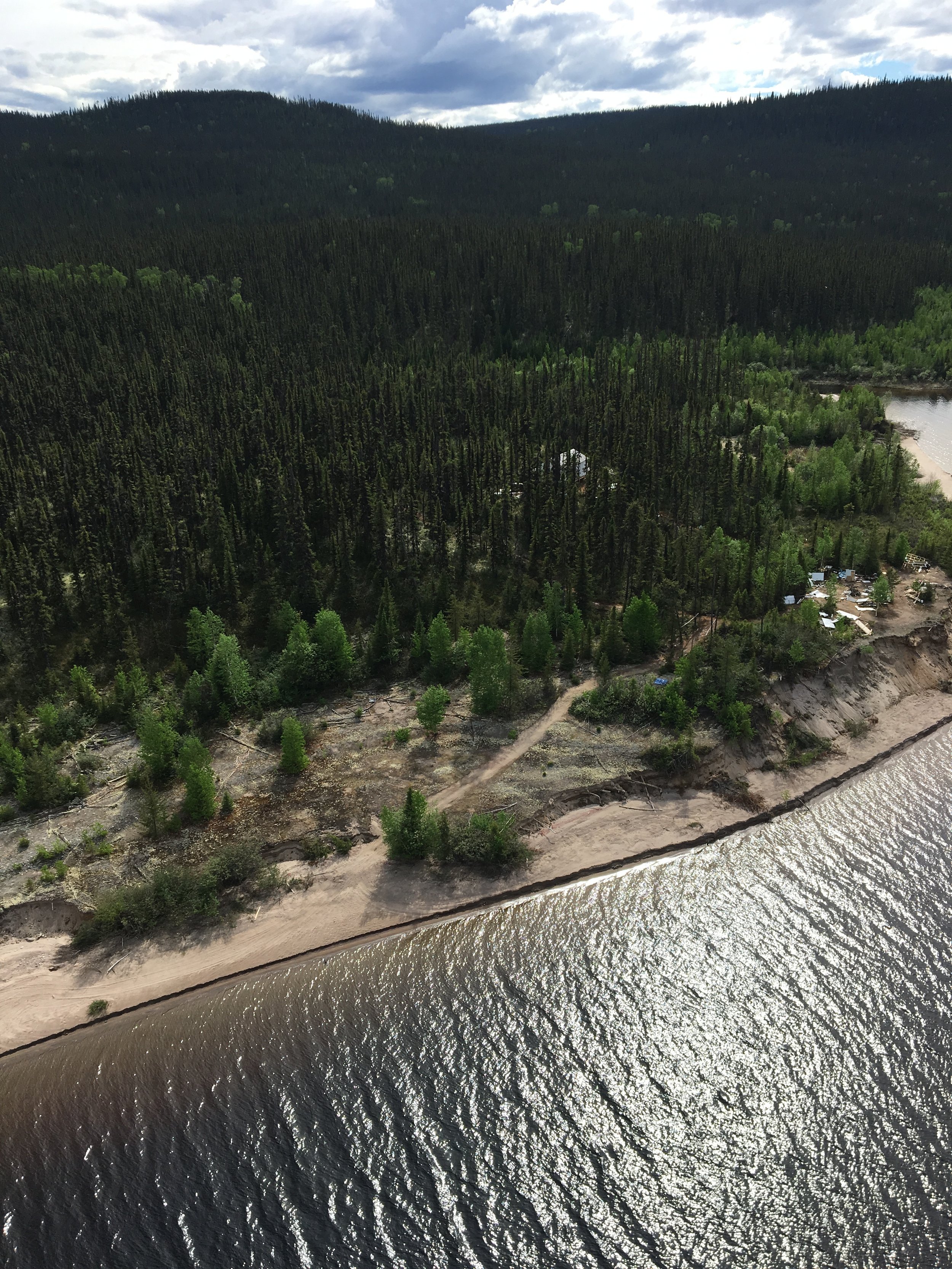

On the Betsiamites, they say, river banks are eroding. Cliffs are falling into the water; camps are threatened; the salmon are virtually gone.

In November of 2017, the Pessamit accused Hydro-Quebec of irresponsibly managing its reservoirs when they discharged large volumes of water into the Betsiamites after autumn flooding. They called the impacts "devastating," and claimed Hydro-Quebec had created "a catastrophic situation that has not occurred since the Manic-Outardes complex was built in 1978 and Bersimis was completed in 1962."

Hydro-Quebec contends the situation was regrettable but unavoidable, a natural disaster resulting from excessive rainfall.

Further north, at the Manicouagan Reservoir, above the massive Daniel-Johnson, the Pessamit have taken the company to court.

Click and drag this 360 video to explore the Manicouagan -- and say hello to Sam and Hannah in the Innu Kopter

On that water-body, a strip of bright green new growth at water's edge serves as a reminder of the height to which Hydro-Quebec once raised the reservoir. And it's the height to which they plan to raise it again -- something they have not done for decades.

In the decades since the Manicouagan was at its legal limit, Pessamit hunters have once again established camps on the bank of the water body. They have built cabins. They eat the fish that they catch. This planned flooding, the Pessamit argue, would destroy camps and introduce more methyl-mercury into the water.

The Pessamit filed an injunction against Hydro-Quebec when the water level-rise began, arguing that the company had neither authorization or right to "contaminate the waters of the Manicouagan Reservoir."

Their argument here is similar to the not-yet official complaint about the Betsiamites: environmental protections are now recognized as important by the Canadian courts. It was not this way when the Manic-Outardes project began, but it is now. And the Pessamit, "like all Quebec citizens," are entitled to a safe and quality environment.

The Manicouagan injunction was temporarily granted, as the courts consider the Pessamit complaint.

Meanwhile, the Pessamit are looking elsewhere for support. They have turned to environmental activists in Canada and the U.S., and linked their fight to that against Northern Pass in the Northeast.

Lawsuits, an international public relations campaign... this is the same playbook that was laid out by the Crees.

The question remains, though, whether this kind of a fight is still a viable one. Especially when the Pessamit's situation is so different: the dams being already built, and the environmental damage already done.

Episode transcript to come -- check back soon.

Outside/In was produced this week by:

Outside/In was produced this week by Sam Evans-Brown with help from: Hannah McCarthy, Taylor Quimby, Maureen McMurrary, Jimmy Gutierrez, and Nick Capodice.

Graphics by Sara Plourde.

Music from this week’s episode came from Blue Dot Sessions and the Aspen Symphony Orchestra.

Our theme music is by Breakmaster Cylinder.

If you’ve got a question for our Ask Sam hotline, give us a call! We’re always looking for rabbit holes to dive down into. Leave us a voicemail at: 1-844-GO-OTTER (844-466-8837). Don’t forget to leave a number so we can call you back.