Powerline, Part IV: Down the Line

When a disenfranchised indigenous community stands up to a corporation, what is righteous and what is wrong seems clear.

But when that fight takes place over decades, the lines start to blur.

Hydro-Quebec is damming another river.

This time it's the Romaine, in the Cote-Nord region of the province. When the project is completed, slated for sometime in 2020, there will be four dams. The company expects to create nearly 1,000 new jobs and generate billions of dollars for the provincial and regional economy.

And this project, like every other Hydro-Quebec has undertaken, will effect access to traditional lands for the indigenous communities who live in the region. In this case, the Innus.

But Hydro-Quebec is not the same company it was in the early days of First Nations conflict.

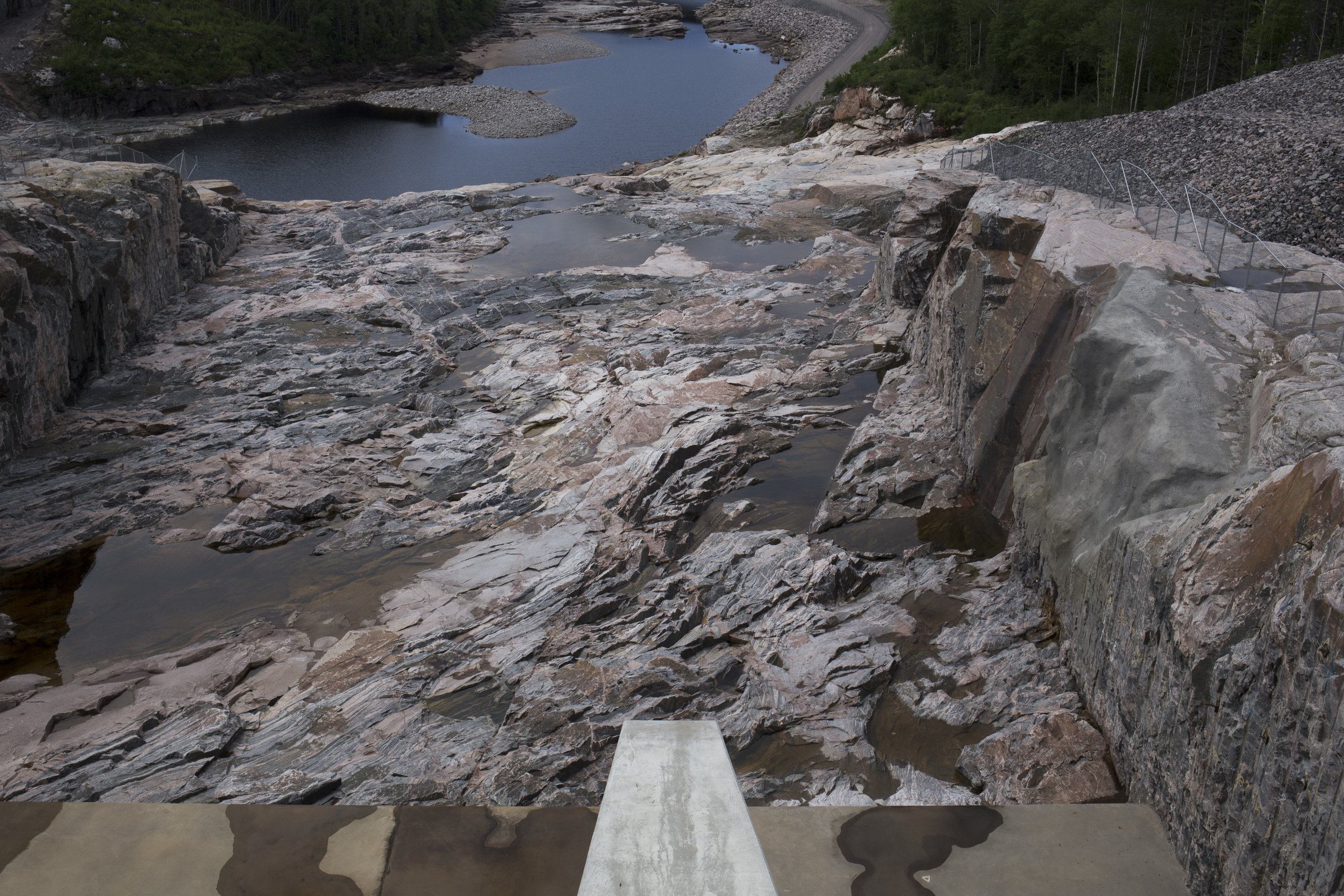

Hydro-Quebec scientist Anne-Marie Prud'homme describes the environmental remediation efforts on the company's latest project

Decades ago, when the Manic-Outardes complex was constructed, the indigenous people of the region were not asked how they felt about the development. Land was flooded and territories transformed without warning. This was problematic, but many would argue not illegal.

Decades of lawsuits, protests and conversation, though, have changed Hydro-Quebec. The company has evolved at the insistence of the province's indigenous people. And law changed, too.

In a 2004 Supreme Court ruling, Canada established the "duty to consult and accommodate." This decision followed a lawsuit filed by an indigenous group in British Columbia who claimed title to forested land. On an appeal, the Canadian court ruled that all Aboriginal peoples must be consulted and their rights maintained should government action have the potential to affect those rights.

So, when Hydro-Quebec looked to dam the Romaine, where indigenous people had hunted, fished and trapped for thousands of years, they approached the Innus first.

What resulted was a series of deals with four Innu communities, negotiated in the early aughts, that guaranteed the Innus millions in monetary compensation, jobs and consultation during construction of the hydro projects. In total, the deal is worth $75 million over sixty years. This money has helped to pay for things like an Innu-owned helicopter company and cultural centers.

An aboriginal-owned helicopter company based in Sept-Iles

And as the company proceeded with their projects, their plan included minimizing the environmental impact of the work. This means monitoring the salmon population and establishing spawning beds, creating ponds and swamps, planting native vegetation, and monitoring woodland caribou.

Hydro-Quebec now hires people who are tasked with ensuring indigenous agreements are met. People like Sonia Burgess, an Aboriginal Affairs Adviser. She's a native of Havre Saint-Pierre who attended high school with Innu children, and who has nieces and nephews on the reservation. Speaking about Hydro-Quebec's relationships with indigenous communities, Sonia teared up and insisted they had good intentions. That the company wants to work with the indigenous people.

Sonia Burgess, a Hydro-Quebec Aboriginal Affairs Adviser, speaks with Sam about her work

Despite Hydro-Quebec's good intentions, the money they provide and the programs they implement, the Innu communities around the Romaine are dissatisfied with the follow-through.

The Innus say consultation has been insufficient; flooding was premature and left behind too many trees; methyl mercury levels are unacceptable. Innus have banded together, with one another and with non-natives, to stage blockades at the entrance to dam work sites.

This continued opposition to hydro development is rooted in something more than of-the-moment concerns. When indigenous communities fight Hydro-Quebec today, it isn't as though the millions of dollars and dozens of deals have scrubbed out the past.

There is no clean slate for Hydro-Quebec and Canada's First Nations.

Chief Jean-Charles Pietacho walks the banks of an island in the Mingan archipelago

Chief Jean-Charles Pietacho of Ekuanitshit did not want to sign a deal with Hydro-Quebec. It was his community who voted to do so.

The first time they received a payout from Hydro-Quebec, the community asked for individual checks. Pietacho, again, disagreed, but followed the will of his people. The next time a hydro payment arrived, Pietacho offered his community an ultimatum: they could have a one-time payment, or they could have him as chief.

Ekuanitshit now puts their Hydro money into a fund, administered by a board of community members and two Hydro-Quebec representatives. And Chief Pietacho is a favorite. He hosts a daily radio show and takes photos of the sunrise every morning to share with his social media followers. He is a constant presence in the community, and to Hydro-Quebec.

Chief Pietacho and former Chief Real McKenzie, Pietacho's right-hand man and translator

This is a chief who plays ball with Hydro, but doesn't go easy. He has the phone numbers of company executives and uses them. He joins blockades and stalls construction. The Ekuanitshit Innu are in dialogue with this company (dialogue mandated by Canadian courts), and take action when that dialogue is dissatisfying.

But all these indigenous people can do is pick their battles as conflict arises. This June, Chief Pietacho was turned away at the gate to Romaine 2's construction site. Though he was free to proceed beyond the gate, the American journalists with him did not have clearance.

Real McKenzie and Chief Jean-Charles Pietacho wait at the gate for Romaine 2

Pietacho was incensed -- not because of a long drive wasted, or a particular desire to show us the site. It was the indignity of being turned away from his own traditional territory. The humiliation of a white guard telling him, a First Nations chief, what he could and could not do.

To Chief Pietacho, this is illustrative of discrimination against his people, not just on the part of Hydro-Quebec, but all white people of the province. Every small sting that First Nations people experience with this company is fraught with generations of land-rights battles, colonialism and personal slights.

Many First Nations people, even those who fought hydro development for most of their lives, are not diametrically opposed to hydro power itself. When weighed against other energy sources, many will tell you it sounds safer, cleaner; climate change should be taken into consideration; people need electricity and it has to come from somewhere.

Hydro-Quebec's development cannot be undone at this point. And as the company moves forward, they will do it in tandem with the First Nations' people whose land they transform. The difference between their modern-day development and that of the past is not simply new environmental or consultation practices. Indigenous communities have established a no-tolerance policy for unfairness. And they are loud and obstructive enough for that to make a difference.

If there has to be hydro power, it will not happen without a fight.

Episode transcript to come -- check back soon.

Outside/In was produced this week by:

Outside/In was produced this week by Sam Evans-Brown with help from: Hannah McCarthy, Taylor Quimby, Maureen McMurray, Jimmy Gutierrez, Nick Capodice and Ben Henry.

Graphics by Sara Plourde.

Special thanks to Lauren Chooljin, Daniel Barrick, Lynn St-Laurent, Jean-Luc Kanape, Ronald Niezen, Kirsten Anker, Frank Magilligan, Kent McNeil, Ryan Coulter, Charles Cusson, Fred Short, Brian Craik, Berchmans Boudreau, Gary Sutherland, Anen-Marie Prud'homme, Sylvain Marsan, Rene Simon, Paul Charest, Pierre-Olivier Pineau, David Massell, Richard Janda, JeanThomas Bernard, Jean-Philippe Gilbert, Carine Durocher, the Cree Trappers Association, Margaret Fireman and the Chisasibi heritage and Cultural Centre and Davey Bobbish.

Music from this week’s episode came from Blue Dot Sessions and Komiku.

Our theme music is by Breakmaster Cylinder.

If you’ve got a question for our Ask Sam hotline, give us a call! We’re always looking for rabbit holes to dive down into. Leave us a voicemail at: 1-844-GO-OTTER (844-466-8837). Don’t forget to leave a number so we can call you back.