Of lab mice and men

At any given time, millions of lab mice are being used in research facilities nationwide. And yet nearly all of them can be connected back to a single source: The Jackson Laboratory in Bar Harbor, Maine, where the modern lab mouse was invented.

What started as a research project aimed at understanding heredity is now a global business. Research on lab mice has led to more than two dozen Nobel prizes, helped save countless human lives, and has pushed science and medicine to new heights. But behind it all is a cost that’s rarely discussed outside of the ethics boards that determine how lab mice are used.

In this episode, we hear the story of how a leading eugenicist turned the humble mouse from a household pest into science’s number one guinea pig. Plus, we get a rare peek inside the Jackson Laboratory — or JAX for short — where over 10,000 strains of lab mice DNA are kept cryogenically frozen.

Featuring Bethany Brookshire, Kristin Blanchette, Lon Cardon, Rachael Pelletier, Karen Rader, Nadia Rosenthal and Mark Wanner.

The Birth of the Lab Mouse

The origin of the modern-day lab mouse traces back to the 1920s. A scientist — and leading eugenicist —named Clarence Cook Little wanted to use in-bred mice to better understand human heredity. He developed a strain of mouse called C57BL6, more commonly known by researchers as “Black 6”, by breeding mice bought from Abbie Lathrop, a prominent mouse fancier in the early 1900s.

As founder of the Jackson Laboratory in Bar Harbor, Maine, C.C. Little advocated for the wider science community to adopt lab mice as the gold standard in model organisms. The lab won major grants in the 1930s to use mice for researching causes and treatments for cancer, and by the mid-20th century, the Jackson Lab became one of the most reputable facilities for research on and the distribution of lab mice, in addition to their own research on conditions like Alzheimer’s and diabetes.

Photos courtesy of Jackson Laboratory.

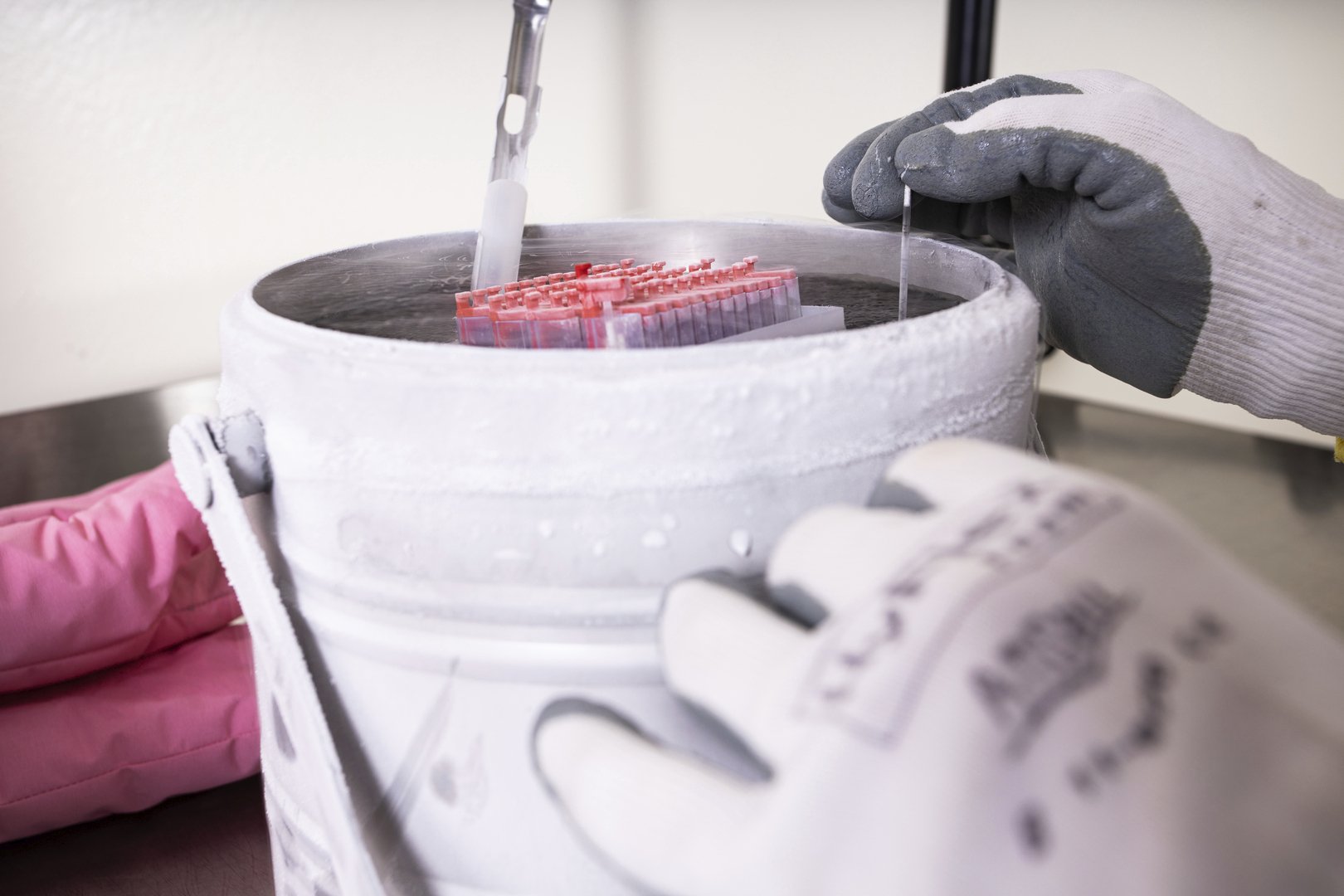

Jackson Laboratory currently has more than 12,000 different strains of lab mice. The lab saves strains through a process called cyro-preservation, in which mice embryo and sperm are kept at temperatures as low as -320 degrees Fahrenheit.

Rachael Pelletier, who work in the in vitro fertilization department of JAX, says the process is a measure for posterity.

“That allows us to not have to take care of mice on the shelf and then we can go ahead and pull those samples out of liquid nitrogen once we have research that we want to use those models for again,” she said.

Our free newsletter is just as fun to read as this podcast is to listen to. Sign-up here.

SUPPORT

Outside/In is made possible with listener support. Click here to become a sustaining member of Outside/In.

Talk to us! Follow Outside/In on Instagram and Twitter, or discuss episodes in our private listener group on Facebook.

Submit a question to our Outside/Inbox. We answer queries about the natural world, climate change, sustainability, and human evolution. You can send a voice memo to outsidein@nhpr.org or leave a message on our hotline, 1-844-GO-OTTER (844-466-8837).

LINKS

Karen Rader’s book, Making Mice: Standardizing Animals for American Biomedical Research, 1900-1955, is a definitive source on the birth of the lab mouse.

Curious to learn more about pests? Take a look at Bethany Brookshire’s book, Pests: How Humans Create Villains.

This piece from the New Yorker questions the assumptions and ethical choices scientists have made by using lab mice in sterilized lab environments.

In this New York Times essay, Brandon Keim explores how some ethicists want to reduce harm to animals used for research through a new model: repaying them.

CREDITS

Host: Nate Hegyi

Produced by Jeongyoon Han

Mixed by Taylor Quimby

Edited by Taylor Quimby, with help from Nate Hegyi, Rebecca Lavoie, Justine Paradis, and Felix Poon

Executive producer: Rebecca Lavoie

Special thanks to Cara McDonough and Sarah Laskowski

Music by Blue Dot Sessions, Spring Gang, and El Flaco Collective.

Our theme music is by Breakmaster Cylinder.

Outside/In is a production of New Hampshire Public Radio.

If you’ve got a question for the Outside/Inbox hotline, give us a call! We’re always looking for rabbit holes to dive down into. Leave us a voicemail at: 1-844-GO-OTTER (844-466-8837). Don’t forget to leave a number so we can call you back.

Audio Transcript

Bethany Brookshire: Do you want to make a mouse happy? Because nothing makes a mouse happier than a Fruit Loop. You give a mouse a Fruit Loop — oh, man. It’s like watching a human eat a car tire.

Nate Hegyi: Bethany Brookshire is an author and journalist. And while plenty of people see mice as pests, she has a special place for them in her heart.

Bethany Brookshire: They eat it all in one sitting. They end and they're like, measurably larger than when they began. That's amazing. And then they just flop off in the cage to sleep it off.

Nate Hegyi: And wait! That’s just a single Froot Loop, right?

Bethany: It’s so cute. Yes, yes.

Bethany doesn’t know about the Fruit Loop thing because she keeps mice as pets. She knows about this stuff because, in a previous life, she used to work as a biomedical pharmacologist studying treatments for things like chronic depression and ADHD.

Bethany Brookshire: And so I would give them their little injection. And most of the injections are given in their little bellies. So you just pick them up in one hand and you tuck the tail with your pinky, because otherwise they'll get in the way and you move their feet and you just give them a little quick shot and then you put them back in. And I would do this at the beginning and at the end of every day, and when I was doing experiments, it would depend on the experiments. So sometimes I would have animals that had been receiving treatment and then I would have behavioral experiments that I would do. I, I put mice in mazes. That is a thing that real scientists do. That is a thing that we do.

More than two dozen Nobel prizes have been awarded for discoveries that relied on mouse studies. Countless drugs, saving countless human lives, were tested first on mice.

Different studies and statements have pegged the total number of U.S. lab rodents at somewhere between 10… and 110 million animals.

And maybe none of this is very surprising, but have you ever wondered… where they all come from?

Like, where does the lab… get a lab mouse?

Bethany Brookshire: There's a catalog and you can just go and say, I would like a mouse with this particular receptor knocked out and they might have it.

Nate Hegyi: How do they ship them to you, by the way?

Bethany Brookshire: They kind of look like KFC containers. You know those round chicken buckets?

[music begins]

Nate Hegyi: Yeah.

Bethany Brookshire: They look exactly like that.

Nate Hegyi: Do you just get it in the mail? Like, is it just like UPS pulls up with a KFC container full of mice?

Bethany Brookshire: Usually it's a pallet. Like, it's a big pallet, but yeah.

[music continues]

I’m Nate Hegyi. Today on Outside/In, we are talking all about mice. Specifically, the careful invention of the world’s most popular model organism: the lab mouse.

We’ll talk about what they are, and why they’re so important in the world of science, AND get a peek inside one of the places where the world’s most relied-upon lab mice are bred and sold every year.

Mark Wanner: We’re at about thirteen thousand strains we’re distributing right now, with different genetic mutations, different genetic backgrounds, all of that. So it’s quite a big operation.

Nate Hegyi: Did you ever wrestle with the ethical questions about using mice? Did it ever make you feel uneasy?

Bethany Brookshire: Constantly.

Stay with us.

[music builds]

Today, there are few different species of rodent used in labs: brown rats and deer mice for example.

But most of them belong to what is arguably the most successful species of them all: Mus musculus.

The house mouse.

Bethany Brookshire From the instant we had houses, we had house mice.

That’s Bethany again, now speaking in her role as a science journalist and author of the book “Pests: How humans create animal villains.”

Bethany Brookshire So this was in the Levant, an area that's now Israel, Palestine, Jordan, etcetera. And this area was the place where kind of humans first tried out housekeeping, just trying it on building these permanent structures…And yet they had mice.

Since that fateful introduction, people have had a complicated relationship with mice. Mostly, we see them as pests — to be caught, and killed, or at least shooed away.But throughout history, they’ve also been worshipped, revered, or kept as pets. And in the 1800s, people in Britain and the U.S. started breeding mice — just like we do with cats and dogs.

Nate Hegyi: Can you actually explain what a mouse fancy is?

Bethany Brookshire: So the mouse fancy is breeding mice for show. There's one called, like, a Russian blue, and it has long blue gray fur. There’s, like, nice little names for the different colors of and like different fur types. There's definitely a mouse that has curly fur. It's like a tiny, incredibly stupid looking poodle.

One of the biggest breeders in the biz was named Abbie Lathrop. Around the turn of the 20th century, she was breeding more than 10,000 fancy mice out of her farm in Massachusetts. She was meticulous in her work. She kept extensive records of what each mouse breed looked like, and how they behaved. This became handy… when some of her mice developed skin lesions.

It was cancer.

[music begins]

Before I go on - I should explain that before the invention of the lab mouse, a lot of scientific experiments were conducted… on dogs. You remember that study about Pavlov’s response? The experiment we were told about in middle school, where scientists conditioned doggos to drool for food when they rang a bell? Well, it wasn’t as cute as you might have imagined. Because those studies involved operating on live canines.

Karen Rader: They basically were opening up dog stomachs in order to see whether or not they were salivating and whether or not acid was being produced in their stomachs.

This, by the way, is Karen Rader.

Karen Rader: And I'm a professor of history at Virginia Commonwealth University.

Back in the early 1900s, operating on animals for research was called vivisection. And the animal activists in those days — the PETA if you will — were called anti-vivisectionists. This was a time of rapid scientific growth — we were just discovering the principles of genetics, evolution, and medicine. But the public didn’t love the idea that gaining knowledge required the dissection of puppies and bunnies.

Mice, on the other hand? To most people, they were just pests.

Bethany Brookshire: When you label something a pest? You say that animal has no value. You say it's okay to do whatever you need to do to get rid of that. And now they have all of this research to people in the research that we do with them. But that value would not be possible without us hating them in the first place.

[music builds and fades]

All right. Back to those mice with skin lesions. So Abbie Lathrop showed her mice to scientists, and they found that some breeds were getting cancer more or less than others. That meant that — like different-colored coats or curly hair — predisposition to cancer was something that was being passed down from generation to generation. And that’s where the father of the lab mouse finally comes into the story.

Karen Rader: That story begins with Clarence Cook. Little…

Karen Rader wrote a whole book about how lab mice came to be. And she spends most of it talking about this guy: C.C. Little.

Karen Rader: Some would say he was outgoing, and visionary, and entrepreneurial. Others would say he was stubborn and he had an administrative style that was very brash and clashed with many people. So he was, like most of us, a mixed bag.

In the 1910s, C.C. Little was a track runner and aspiring zoologist at Harvard. He thought mice were the future of animal research. And what he wanted to do was study the genetics of mammals.

Karen Rader: So within that framework, what he decided he was going to do was try to use mice to understand human heredity.

He did this the same way the mouse fanciers did: through in-breeding. By mating each round of mice with close relatives, they could isolate traits and learn more about how they were passed down. It’s basically the analog form of genetic modification. You don’t need Crispr, or any special equipment of any kind really. All you need to do is pick who mates with who. So, Little got to work. And by the 1920s, he bred his first strain from Abbie Lathrop’s fancy mice. And he named it the C57BL6.

[music builds]

A couple things about the C57BL6… or Black 6, as it’s often called. It’s got a dark brown coat. It displays a trait called “barbering” - where dominant males will pluck fur or whiskers off of other mice. Also, it likes alcohol and is more susceptible to morphine addiction than other strains of mice. But probably the most important thing you should know about the Black Six is that it is one of the most popular, most widely used strains of lab mice in the world. And that’s in part, thanks to the automotive industry.

[parlor music begins]

Man from archival clip: Here are some most happy fellows. The four lads for Ford!

Men singing from archival clip: Standing on the corner…

[parlor music fades]

After college, C.C. Little went on to become president of The University of Maine. And while he was there, he rubbed shoulders with some of the folks vacationing in the famous town of Bar Harbor. Among them was Roscoe B. Jackson, president of the Hudson Motor Company. He introduced Little to other bigshots, like Edsel Ford,

Karen Rader: who was the son of Henry Ford and the head of Ford Motor Works,

And Richard Webber,

Karen Rader: who was the head of the now defunct J.L. Hudson Department stores.

They all were guys who specialized in mass production, and they saw potential in C.C. Little’s mice. Just like how cars were being churned out in uber-efficient assembly lines, they envisioned a lab where you could bring the principles of mass production… to science — by pumping out genetically modified mice. So the automakers helped C.C. Little fund a brand new lab: The Jackson Laboratory.

[music]

Now if pumping out mice via assembly line - which is just a metaphor by the way, that’s not how they actually do it - if that sounds a little dystopian to you, you’re not alone. Because behind the invention of the lab mouse is an undeniable fact: C.C. Little was a leading eugenicist. He believed that the selective breeding programs he used for mice - could also improve the quality of human beings, as a species.

Karen Rader: And in 1928, he delivered an address at the Third Race Betterment Conference in Battle Creek, Michigan, sponsored by Kellogg.

That’s John Harvey Kellogg - the guy who patented that famous cereal. Although I should say it was his brother who went on to found the company we all know today. Anyway, this was a conference with talks like “The Menace of the Melting Pot Myth”... and, “Race Betterment - what can we do about it?”

Karen Rader: And he said, quote, “Many people are born more or less defective in one or another of their constitutional elements. And in the correction of these deficiencies, we are to make real advances.” Unquote.

Now C.C. Little didn’t just speak at this conference - he was the President of the conference. That makes him a key American leader for a global movement that promoted forced sterilization programs in the U.S. and other countries… and inspired the Nazi Holocaust during WWII. There was no scientific basis for the eugenics movement. It’s been discredited repeatedly by scientists as a thin veil for ableism, bigotry and white supremacy.

C.C. Little himself backed away from his views of eugenics during WWII, as the Holocaust showed the extent of the destruction, xenophobia and hate that eugenic values fuel.

But people haven’t forgotten his connection to the movement… Which is why a couple of buildings named after C.C. Little have been renamed over the past few years.

But where scientists would eventually turn against the eugenics movement for humans - the same principles are central to the very concept of C.C. Little’s lab mouse.

Bethany Brookshire: Yeah, and that was actually one of the selling points when C.C. Little went to sell mice to the public and most particularly to scientists. The idea that you could create these rigorously controlled experiments that kind of take the scientific method to a really, really extreme place where we can carefully control for so many variables and only change the things that we want to see.

[music begins]

This was the first selling point Little gave to the wider scientific community about the lab mouse. So much of science is trying to eliminate variables… And in-bred lab mice are a practically unlimited source of genetically similar test subjects. Pitch Number Two: Humans needed mice to help find cures for diseases. Diseases like cancer, which scientists at the time didn’t know much about.

Karen Rader: Throughout the teens and 20s cancer was becoming both a publicly and a scientifically interesting disease. But it was actually Roscoe B Jackson,

That was one of C.C. Little’s biggest donors —

Karen Rader: who pushed Little to understand that there were public health aspects to doing research on mice and mouse cancers. And he even promised him that might be a way to get more funds because he said, all of my friends will be interested in this because everyone has had a friend or a family member touched by the disease of cancer.

And finally, C.C. Little convinced the scientific community - and the public at large - that mice were the perfect lab animal because…. Well, because they were mice.

In 1937, he wrote a fiery piece in the Scientific American, called “A New Deal for Mice.” It goes like this:

Karen Rader: Do you like mice? Of course you don't. Useless vermin, disgusting little beasts or something worse is what you are likely to think as you physically or mentally climb a chair. So with that colorful image in place as the starting point, he said, Let me be the attorney for the defense and tell you how mice in their involvement with science have been positively transformed.

At first, all of this PR work was in service of The Jackson Laboratory’s research arm - which was studying cancer and mammalian genetics. But when the Great Depression hit, donors drastically cut their contributions. And C.C. Little had to think of something else to keep the research going.

Karen Rader: I think he really wanted to find the causes for cancer, But the raw truth of the economics at Jax at that time was they needed to sell mice if they were going to stay alive. … So in the end, it was financial hardship that prompted a kind of consumer-centered ethos and almost completely took over the labs original goal of breeding and using inbred mice to solve genetic riddles that went beyond cancer.

In other words, the Jackson Laboratory - or JAX lab, for short - became the number one source of inbred lab mice. They developed new strains with traits specifically designed for different kinds of research. And sold them to universities and private labs around the country by the KFC bucketload.

Karen Rader: Mice became a kind of scientific bandwagon. That's a term that sociologists use to talk about the ways that research areas become hot in certain times.

C.C. Little eventually moved on from the Jackson Laboratory to work with the tobacco industry. But there’s no question that his mission worked - the Jax Lab created a whole new paradigm in scientific research. In the 1990s, a JAX representative claimed their lab mice accounted for 95 percent of all lab mice worldwide.

Today, researchers from across the world can order them online. There are strains ideal for researching Alzheimer's, ALS, and Type 2 diabetes. You can buy lab mice young, or pre-aged, you can buy frozen mouse embryos or frozen mouse sperm. And without them - we would be decades behind where we are now in science and medicine. Organ transplants? Made possible because of research on JAX mice. The Covid vaccine? If it weren’t for JAX, we wouldn’t have gotten it for another 5 or 6 months.

[music fades]

But all those advances come at a cost - one that many people would prefer not to think much about. Because even if it’s worth it… it’s not a pleasant trade-off.

Nate Hegyi: Did you ever wrestle with the ethical questions about using mice? Did it ever make you feel uneasy?

Bethany Brookshire: Constantly.

That’s Bethany Brookshire again.

Bethany Brookshire: And I've never met. A scientist who does not think about that.

Nate Hegyi: And what about it made you uneasy or question it?

Bethany Brookshire: Well. You know, we work with hundreds of mice. Those mice do not live past the end of that experiment.

Nate Hegyi: So you've had to kill mice before?

Bethany Brookshire: Yes.

Nate Hegyi: How do you — how do you kill the mice?

Bethany Brookshire: So there are several ways you have to keep in mind that. Mice are not covered under the Animal Welfare Act. They're covered under a different piece of legislation. But there is, there are laws around what you can and cannot do. And every experiment that I ever did went through something called an Iacuc, which is an internal animal care and use committee. And this is a group of people that are gathered by the university. They are volunteer, and some of them are scientists, some of them are administrators. And there's always at least one member of the public. Apparently the that's really big among clergy, like almost everyone in the clergy, has served on an IACUC [Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee] is like a thing that they do. Yeah. And so every time I wanted to do an experiment with animals, I had to write up a full application for the cook. I had to submit it and say like, This is what I'm going to do if I do surgery on these animals, here is how I'm going to take away their pain. Here is how I'm going to anesthetize them for surgery. Here's what I'm going to do during recovery for surgery to make them feel better. Here is how I'm going to acceptably sacrifice my animals and for what reason? Right. And so there are a couple of approved ways in which you can sacrifice mice. The ways that I am most familiar with are chambers with CO2, which are very fast. And the one that I usually did, which is called cervical dislocation. That's breaking its neck. That is what I had to do because I needed their blood samples and I also had to extract the brain and take brain samples. So I would be racing around, you know, kind of dissecting out this brain very, very quickly. Yeah.

Nate Hegyi: What was your kind of process? How would you — how would you break the neck?

Bethany Brookshire: Scissors.

Nate Hegyi: Scissors. Okay. Yeah.

Bethany Brookshire: You just put the scissors on the back of the mouse's neck behind the head, and then you pull the tail up really fast.

Bethany would do what she could to make their lives better — as all labs are required to. But the extra care, the compassion, the Fruit Loops… all of that only went so far to fight off her feelings.

Bethany Brookshire: It never goes away. And for many people, when they're first learning, when they're in graduate school or even undergrad, it can be really, really emotionally very upsetting, sometimes even traumatizing. And when I would train students about this and I would always try to prepare them and say like, you know, here's what's going to happen. You need to recognize that what we're doing is tough and it's ethically fraught. And I just, you know, want to note that, you know, scientists are not unfeeling monsters about this sort of thing.

[music swells]

After the break…we send one of our producers inside the lab that started it all - the Jackson Laboratory. We’ll be right back.

[BREAK]

NATE: This is Outside/In, I’m Nate Hegyi. Today, the Jackson Laboratory is still one of the biggest providers of lab mice in the world. But it’s not quite what it was a few decades ago - and its founder, the eugenicist C.C. Little, no longer has his name on any of the buildings. But we wanted to know… what does it actually look like inside the Jackson Lab? What does mouse breeding look like in 2023?

So we sent our producer, Jeongyoon Han to Bar Harbor, Maine to find out.

Jeongyoon Han: And I'm walking to the visitors entrance.

Jeongyoon Han: Acadia National Park is one of THE summer go-to spots in New England. But in one little corner of the park, you might notice a faint odor mixing in with the sea breeze.

Jeongyoon Han: It smells a little weird. I don't know. [SNIFFS AIR] It smells like a pet store.

This is, of course, the headquarters of Jackson Laboratory, and it’s huge. 169 acres huge.

Mark Wanner: We try to blend in so much that people won’t be like, what is that big thing doing? Or, you know, and if they do know the mice, they tend to be really excited - like oh, I used to work with them when I was in grad school, you know, whatever. And so it's pretty fun.

This is Mark Wanner - associate director of research communications at JAX.

Mark Wanner: So we have a lot of, like neuroscience in this building downstairs. But they're also aging and cancer research, um, stem cell research.

Inside, it almost looked like a really fancy university science building - with state-of-the-art lab benches, equipment and specialized research wings.

Jeongyoon Han: It looks like it. Is that a fitness? Are those. Is that a fitness center?

Mark Wanner: Yeah. It's named after Douglas Coleman, who was an early metabolism researcher. And he found leptin.

Jackson Labs is still a two-part operation. They do a lot of their own scientific work, studies on things like Alzheimer’s and rare diseases like Huntington’s.

Mark Wanner: This is the East Research building - we name things very prosaically here. This is the East Research Building and over…

They collaborate with lots of different organizations, and once, even sent mice into space to research muscle mass and bone density. On the other hand - they’re still supporting that work through the breeding and sale of different strains of lab mice.

Mark Wanner: We’re at about thirteen thousand strains we’re distributing right now? Yeah so thirteen strains of mice with different genetic mutations, different genetic backgrounds, all of that, so it’s quite a big operation.

The scale here is pretty staggering. JAX has nearly a dozen facilities in 3 different countries. In 2021, they reported over 350 million dollars in revenue from quote “genetic resources”. That money dwarfs what JAX makes every year from research grants and contributions. And whole areas of the campus are dedicated to housing, and taking care of their animals.

Jeongyoon Han: Okay, so what are we looking at?

Mark Wanner: So it's a large silo looking thing, probably a few stories high, and it's a container that holds wood pellets like pellet stoves, exactly the same thing. You can smell the wood.

Jeongyoon Han: I can smell it. Yeah.

Mark Wanner: Yeah. And so you know what people think mice smell like actually smells like the cages and the and the the the bedding. And so when they're sterilizing the bedding for the mice because it all gets sterilized in huge autoclaves, it smells like wood, too. So sometimes there's an ambiance around here, let's just put it that way.

Jeongyoon Han: An ambiance of what?

Mark Wanner: Of mice, you know, of. Of the wood shavings of the, the chow. They sterilize the chow.

Jeongyoon Han: Chow?

Mark Wanner: The mouse food. So…

Jeongyoon Han: What do mice eat?

Mark Wanner: Chow.

[Both laugh.]

Like a lot of details about how JAX Labs operates – the folks here wouldn’t tell me exactly what that means.

Jeongyoon Han: What do you feed mice?

Kristin Blanchette: Our mice are fed on commercially available diets.

That’s Kristin Blanchette. She runs quality control programs at JAX.

Kristin Blanchette: I don’t know if you want me — We can't — we can’t disclose the, the product just because for proprietary reasons.

“Proprietary reasons” also kept me from peeking at something I REALLY wanted to see, which is the place where they keep the mice — called a vivarium.

Kristin Blanchette: Like I don't want to go into, like, super super detail for you because it's hard to explain without seeing it.

If I did have access, though, I’d have to go through a full-on air shower, put on PPE, and sanitize everything. It’s to keep the mice safe from outside germs.

Kristin Blanchette: There are housing racks with cages that have the animals plus supplies in the rooms, and then there are also environmental factors that are monitored. So we're talking about light cycles, temperature and humidity, and all of that goes into ensuring that the animals are cared for appropriately.

Jeongyoon han: I didn’t even think about light. They don’t like light?

Kristin Blanchette: Well nobody wants to have light 20, 24 hours a day.

Jeongyoon Han: That makes sense.

Kristin Blanchette: We set light cycles for them so that they can stay within, stay in their circadian rhythm.

But given all of the tight security, I was surprised when the folks at JAX suggested I visit this one room… The Biobank.

Rachael Pelletier: So welcome to the Biobank.

There aren’t any mice that live here - but there’s lots of mouse DNA. Rachael Pelletier is one of the people who work with these huge, 4 5 foot tall tanks.

Rachael Pelletier: These tanks hold liquid nitrogen, some tanks hold samples with embryos and other tanks hold sperm. There could be a combination of both.

JAX takes these samples and does something called cryo-preservation with them. Which means they keep samples at really low temperatures — as low as -320 degrees Fahrenheit.

Mark Wanner: But, yeah. JAX was the first place to figure out how to cryopreserve and then sort of regenerate sperm.

They preserve these strains so that scientists across the world can grab them when they actually need them. Lab mice only live about two years. Embryos - like diamonds - are forever.

Rachael Pelletier: To your question, a big benefit of cryopreservation is being able to freeze down mouse models. And that allows us to not have to take care of mice on the shelf and then we can go ahead and pull those samples out of liquid nitrogen once we have research that we want to use those models for again.

So if you do the math,

Rachael Pelletier: So we're going to look inside of Tank 25.

Each tank has 92 racks,

Rachael Pelletier: Each rack holds four boxes. Each box holds 48 cassettes.

And in each box, there are five straws.

Rachael Pelletier: So that's a total of 88,320 straws per tank.

And those straws each have around 4-5 samples of embryos or sperm.

Rachael Pelletier: So we have frozen 5.6 million embryos. About 10,000 of the 12,000 strains we distribute exist only as frozen material.

Jeongyoon Han: Wow, wow.

So when a lab makes a request for a specific strain of a mouse — they’ll go on JAX’s website, which lists all of the different breeds they have in a virtual catalog — and pick up the right sample. Then JAX opens up the Biobank and they’ll have the sperm fertilize the embryo and let it grow in a petri dish, and they wait until it’s doubled to a certain size.

Rachael Pelletier: Yes, they're very fragile. And you have to be really gentle through embryo handling. We do mouth pipetting. So we would put the mouthpiece in our mouth and actually breathe in, suck in to be able to pick up the embryos into the very tip of that pasture pipette.

Jeongyoon Han: And then and then you just roll it around like using, like mouth suction?

Rachael Pelletier: Yes, exactly. Yep.

Jeongyoon Han: Whoa.

Rachael Pelletier: And then through embryo transfer, we can put those into pseudo pregnant females as well.

Jeongyoon Han: Pseudo pregnant females.

Rachael Pelletier: Females that have been mated with a male that has had a vasectomy. So that kind of tricks the female's body to think that she just made it naturally with a male and that she's going to become pregnant. Mhm. Okay. And then we would go ahead and do the embryo transfer surgery and we would put those collected embryos from that have been created through IVF into the oviduct of the female.

Jeongyoon Han: Got it. Got it. It's fascinating. I was an IVF baby. Well, actually, I think my my sister was and then I came a year later, so.

Rachael Pelletier: That's amazing. I love that.

Jeongyoon Han: Yeah. [Laughs.]

[music]

Earlier in the episode we talked about all of the advantages to using mice as test subjects: that we can in-breed them, eliminate variables or engineer them to be susceptible to cancer, or diabetes.

Today, there’s another big reason to keep using mice for research.

Inertia.

Nadia Rosenthal: The reason that lab mice are so valuable now is because of the 100 plus years of research that's gone on all over the world to understand these little creatures.

This is Nadia Rosenthal. She directs JAX’s research side of the company’s work. Nadia says without those mice, it would have taken scientists WAY longer to find really crucial scientific discoveries that have directly benefited humans.

Nadia Rosenthal: You're going to be waiting a very long time to see how a particular genetic change is going to affect a primate when they're the equivalent of 30 or 40 years old, when, for instance, someone who has Huntington's disease may come down with the disease at a late onset. In a mouse you can do that in. Months. And so this shortened lifespan is extremely useful when you're looking at adult onset disease.

[music fades]

We make all of these justifications to tell ourselves, it’s necessary to use mice for research. But… is it right?

A few years ago, there were a number of negative headlines about the ‘forced swim test’, where mice are dropped into water tanks to see how long they’ll try to stay afloat. It’s a test used to study depression - but animal rights activists and some scientists say it’s unnecessary, cruel, and basically, bad science.

And there are even more scientific drawbacks. Some say that the clean, sterilized nature of labs doesn’t represent the real world - that studying lab mice gives us an incomplete picture of whatever we’re studying.

Another pitfall of the inbred mice model - really, a pitfall of the entire concept that C.C. Little championed all those years ago - is that all of these mice ARE different. Even if they have the same color or some of the same habits, every Black 6 mouse is its own unique self.

And that diversity — it’s actually a gift.

Nadia Rosenthal: So what the scientists here at the Jackson Laboratory have spent the last two decades really working on hard is to actually go backwards and look at the way in which mice are diverse within the actual species, rather than to try to make every mouse the same as every other mouse.

Jeongyoon Han: Hmm.

Nadia Rosenthal: The reason we're doing this is because we want to try to model the human diversity that we're seeing in populations around the world in our model, in our mouse model.

All that makes sense to me. But there’s something I still can’t quite square – about how we talk about lab mice. It’s like, once they were vermin… but now they’ve been redeemed as heroes… as useful to society.

There’s even this big bronze statue in Siberia, dedicated to the lab mouse. It’s wearing a lab coat and glasses, and knitting a double helix. But they didn’t sign up for this. They didn’t ask for a statue - They don’t even know what a statue is. These kinds of celebrations feel like they’re more for us, than it is for them. Our strange way of saying thank you for a choice they never made…But one that we’ve thrusted on them.

When I sat down with Jax’s CEO, Lon Cardon, I asked him if there’s a world where there is no such thing as a lab mouse.

Jeongyoon Han: Um, kind of on this line, it might be a little bit touchy, but do you think we'll ever get rid of using mice in scientific research?

Lon Cardon: It's, um, it may seem a touchy question, but it's one I get asked just about every day. I don’t. I spent the last 15 years of my life in industry trying to make drugs for diseases. And I think it would be, at this time and in the foreseeable future, hugely irresponsible to put an investigational drug into a human without having tested that in a whole organism, whether it's a mouse or something else. I think that that would assume we know so much more about human biology and how the body works than we really do. So I think what will happen is the way we use mice will change, but they're not going away.

Bethany Brookshire: Yeah, I mean, a lot of that is about us being dominant, right? And it's really interesting because I talk to a lot of ethicists for my book, and one of them said, look, it doesn't matter what ethical system you ascribe to, if you put an ethicist in a chair and you won't make them leave until they answer the question in a burning building, who are you going to save a baby or a kitten? Every single ethical system cracks and picks the baby.

Again, here’s former lab researcher and current science journalist, Bethany Brookshire.

Bethany Brookshire: In the end, we choose our own species and we do things for the benefit of our own species. And I don't know if that is biological. I don't know. Like that's not my job. But I do think that it plays into how we use animals in our lives. You know, in the end, we're here to benefit ourselves. And that sometimes means that we use other animals.

This episode was produced by Jeongyoon Han.

It was mixed by editing by Taylor Quimby, with help from me, Nate Hegyi, Justine Paradis, and Felix Poon.

Our Executive Producer is Rebecca Lavoie.

Have you ever worked with lab mice, or other model organisms? Tell us about your experience, or what you thought about this episode - our email is outside in at nhpr dot org. We always love hearing from you.

Music by Blue Dot Sessions, Spring Gang, and El Flaco Collective.

Our theme music is by Breakmaster Cylinder.

Outside/In is a production of New Hampshire Public Radio.

Note: Episodes of Outside/In are made as pieces of audio, and some context and nuance may be lost on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors.