The papyrus and the volcano

While digging a well in 1750, a group of workers accidentally discovered an ancient Roman villa containing over a thousand papyrus scrolls. This was a stunning discovery: the only library from antiquity ever found in situ. But the scrolls were blackened and fragile, turned almost to ash by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius.

Over the centuries, scholars’ many attempts to unroll the fragile scrolls have mostly been catastrophic. But now, scientists are trying again, this time with the help of Silicon Valley and some of the most advanced technology we’ve got: particle accelerators, CT scanners, and AI.

After two thousand years, will we finally be able to read the scrolls?

Featuring Federica Nicolardi, Brent Seales, Youssef Nader, Arefeh Sherafati, and Julian Schilliger.

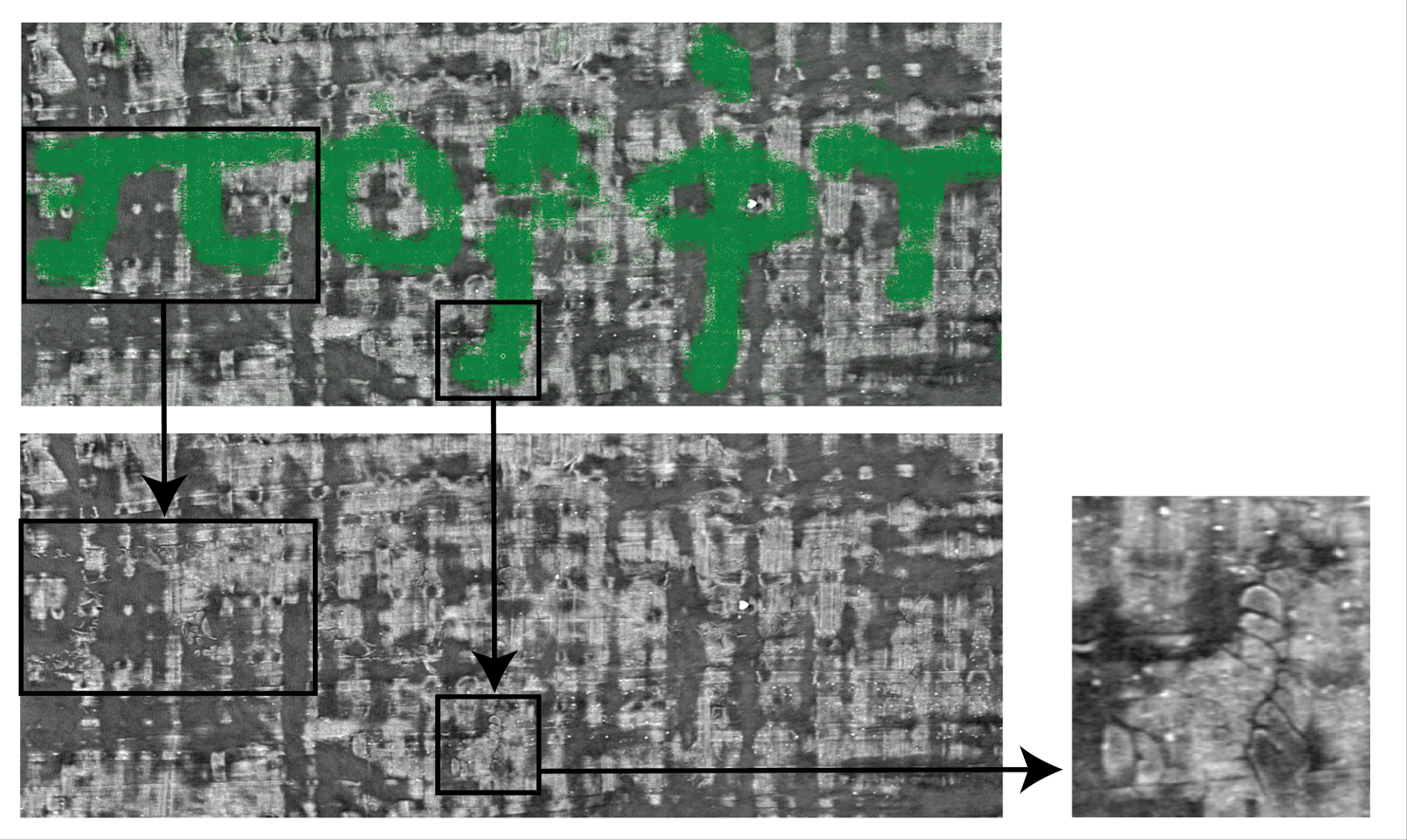

An animation depicting the process of "virtual unwrapping." Courtesy of the Vesuvius Challenge.

Click images to enlarge and for more info.

LINKS

The Vesuvius Challenge is not over. Find out more here.

Check out more pictures of the scrolls and the process of “virtual unwrapping” at the Digital Restoration Initiative website, or watch Brent Seales lecture about his technique.

A video illustrating the process of “virtual unwrapping” with a jelly roll.

A 60 Minutes story (2018) focusing on the conflict between Seales and scholars Vito Mocella and Graziano Ranocchia.

A replica of the marble floor discovered by Italian farmworkers in 1750.

Contestant Casey Handmer’s blog post detailing his identification of the “crackle signal” to the ink.

CREDITS

Outside/In host: Nate Hegyi

Reported, produced, and mixed by Justine Paradis

Edited by Taylor Quimby

Our team also includes Felix Poon.

NHPR’s Director of Podcasts is Rebecca Lavoie.

Music in this episode came from Silver Maple, Xavy Rusan, bomull, Young Community, Bio Unit, Konrad OldMoney, Chris Zabriski, and Blue Dot Sessions.

Volcano recordings came from daveincamas on Freesound.org, License Attribution 4.0 and felix.blume on freesound.org, Creative Commons 0.

Outside/In is a production of New Hampshire Public Radio.

Audio Transcript

Note: Episodes of Outside/In are made as pieces of audio, and some context and nuance may be lost on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors.

Justine Paradis: Hey Nate.

Nate Hegyi: Hey Justine!

Justine Paradis: Our journey today begins in Italy. Way back in 1750.

MUSIC: Tell Me What You Know stems, Blue Dot Sessions

On the southwestern coast, right on the Mediterranean. A group of people are busy digging a well. And while they’re digging, their shovels start to hit not soil – but this [replica].

Nate Hegyi: Whoa! They hit what looks to be… is that tile?

Justine Paradis: Yeah it’s like a mosaic. To me it’s almost fractal-y.

Nate Hegyi: It looks like marble rug. It’s beautiful.

Justine Paradis: It’s beautiful. It turned out that this was a patterned marble floor, which had been buried in volcanic ash, because this villa was once part of the ancient town of Herculaneum, just outside of Pompeii.

Nate Hegyi: Oh, that Pompeii.

Justine Paradis: The one that was completely buried by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, almost 2000 years ago.

Justine Paradis: Right? So… People eventually figured out that this villa probably belonged to Julius Caesar’s father-in-law. So, it was lavish, complete with dozens of bronze + marble statues, and an Olympic swimming pool. But the real treasure was in the library.

MUSIC: Eridanus, Blue Dot Sessions

Justine Paradis: Excavators found hundreds of papyrus scrolls, each containing invaluable writings on classical philosophy.

Federica Nicolardi: Philosophy in antiquity means a lot of different things. … ethics, rhetoric. It can mean poetic. It can mean music, in this case. It can also mean, uh, physics…

Justine Paradis: That’s Federica Nicolardi, a papyrologist at the University of Naples.

Nate Hegyi: Papyrologist!

Justine Paradis: Isn’t that such a nice word? It’s a discipline.

Nate Hegyi: “I’m a papyrologist.”

Justine Paradis: We don’t have a ton of writings from antiquity — a lot of it has been lost to time. Actually, this collection of scrolls — this is the only surviving library ever discovered from the Roman era. Hundreds of never-before-seen original texts. It’s hard to emphasize how big of a deal that is.

MUSIC FADE

Federica Nicolardi: Each of the book that we have from the library is a unique book. So these texts are all completely new. We don't have them from any other tradition. We don't have them from medieval manuscripts or any other tradition. So everything we read there is completely a new, it's a new achievement, a new result.

Justine Paradis: Or, they would be … if the scrolls hadn’t been completely carbonized by the scorching temperatures of the volcanic gasses.

Nate Hegyi: Oh no.

MUSIC: Superior, Silver Maple

Justine Paradis: So since they were discovered in the 1750s, these 800-or-so scrolls, have pretty much sat. In drawers. In a library. As people fought the American Revolution. When Abe Lincoln was shot. When the Internet was invented. When your great-grandparents were born and when they died. When the internet was invented. When you applied to college. They were sitting.

Nate Hegyi: In drawers.

Justine Paradis: Pretty much. Most of them, together at least, they likely have the power to not only enrich, but potentially transform our understanding of antiquity and ancient philosophy.

Nate Hegyi: Right. But we can’t read them.

Justine Paradis: If only we could read them.

MUSIC SWELL

Nate Hegyi: This is, of course, Outside/In. I’m Nate Hegyi, with our producer Justine Paradis. For centuries, people have tried to read these damaged scrolls. All of them have basically failed… UNTIL NOW.

Federica Nicolardi: I was like, uh, so can I, can can I be happy about it? Is this real, or is there any chance that it is a fake or something?

Arefeh Sherafati: To know I was among the first people, maybe, to set eyes on this unread text. I was almost in tears.

Nate Hegyi: What you got now, Vesuvius?! What you got now? Take it away, Justine.

MUSIC SWELL AND OUT

Justine Paradis: Let’s start with paper. Modern paper is manufactured from tree pulp. Medieval European parchment, which is the stuff of illuminated manuscripts – that’s made from animal skins. But before either, there was papyrus.

MUSIC: Let There Be Rain, Silver Maple

It’s named for the papyrus reed, which grows plentifully in Egypt along the river Nile.

To make papyrus, the stem of the reed is sliced into strips, and then arranged in a kind of grid. One layer of overlapping strips laid horizontally, and then another layer, laid vertically. So, each sheet of papyrus is actually two sheets thick.

Papyrus is flexible. You can roll it into scrolls. It’s also light, far lighter than earlier writing surfaces, like stone or clay, and thus it’s more portable.

The invention of papyrus helped enable the spread of

writing, knowledge, and culture across the ancient world.

But papyrus is also fragile.

SFX: Filtered & Amplified Mt. St. Helens eruption shared by daveincamas on Freesound.org, License Attribution 4.0 and Volcano Mount Yasur, Tanna Island shared by felix.blume on freesound.org, Creative Commons 0

When Mount Vesuvius erupted, hot volcanic gasses flooded into the villa in Herculaneum. They scorched and blackened the scrolls. But paradoxically, they also preserved them. If they had not been carbonized and buried, the humidity of the Italian coastline would have destroyed the papyrus centuries ago.

Volcano Mount Yasur, Tanna Island shared by felix.blume on freesound.org, Creative Commons 0

MUSIC OUT

Today, these scrolls don’t really look like scrolls. They look kind of like the charred wood pulled out of a campfire the next day. Back in the 1750’s when the villa was being excavated, at first people thought they were just lumps of charcoal, and threw many of them away.

Brent Seales: They looked terrible. They're completely blackened, fragile in a way that's almost scary… and it really is almost impossible to imagine that you can read anything.

That’s Brent Seales. He’s not a classical scholar or a papyrologist, but a computer scientist. For decades, he’s been on a quest to read the Herculaneum scrolls.

MUSIC: Dany PKL stems, Blue Dot Sessions

When Brent was starting his career, this thing called the Internet was just starting to get big. And he was thinking a lot about digitizing library materials.

Brent Seales: So I was coming at the digital library in the 90s with the idea that Google had, which, that we wanted to get everything online and be able to index it and find it and use it.

But he quickly realized that libraries and museums have a lot of materials which are not at all easy to digitize.

Brent Seales: And in that category were these things from the ancient world like manuscripts and, and ultimately the scrolls that we discovered from Herculaneum.

Many of the scrolls found in the Villa dei Papyri are still unopened. Rolled up, like a burrito. Unrolling them has not always gone well. There was the museum director, who cut them open. There was the Vatican scholar, who invented an “unrolling machine.” And there was the Neapolitan prince who thought he could use mercury to open them. He tried three times and destroyed three scrolls.

MUSIC FADE

Instead of physically unrolling a fragile manuscript, Brent wanted to try scanning them using X-rays and CT scans.

Brent Seales: Yeah, I mean, that was exactly what we thought: if we can image something wrapped up or a book that can't be opened, then we could virtually pull the pages out.

Brent calls his technique “virtual unwrapping.” This is extremely hard to describe so we’ll put a link to a video in the show notes. But I’m gonna give it a go.

Brent’s idea was to X-ray the scroll in extremely high resolution – high enough to create a three-dimensional model that could depict not only the internal spiral of the scroll, but also reveal the ink on its surface.

Then, he would digitally unroll and flatten out the image.

He’d already used these techniques to image a medieval copy of Beowulf, and to read The Ein Gedi Scroll, a Hebrew bible written in the third or fourth century on animal skin, found in an ancient synagogue.

But to read the Herculaneum papyri, he’d have to take his technique to the next level. In 2019, Brent scanned two scrolls using a synchroton, an actual honest-to-goodness particle accelerator.

MUSIC: Dany, Volda Synth stem, Blue Dot Sessions

It can scan objects at resolutions that are literally microscopic –

Brent Seales: at the super high resolution of eight microns per voxel, which eight microns is about the size of a red blood cell.

A voxel, btw, is just a 3D pixel – pixels are 2D.

Brent Seales: Clearly, it’s the golden data set.

MUSIC FADE

But now, there was a new challenge. The synchrotron had produced an absolutely enormous amount of data. These 3D models of the scrolls would take years “virtually unwrap”, let alone read.

So, Brent had his work cut out for him. But then, something happened that he wasn’t expecting.

MUSIC: Zig Zag Heart, Blue Dot Sessions

Brent Seales: I got cold called by Nat Friedman, summer of 2022… Didn't really believe it was him.

If you’re a developer, Nat Friedman is a big deal. He founded Github, a platform for developers, particularly in the open source community. He’s now an investor, active in Silicon Valley, putting a lot of money into AI.

At this point, with the synchrotron scans, the bottleneck to reading the scrolls was really time and labor. It needed a lot of people giving the problem their attention. So, Nat wondered, why not bring an open-source mindset to the problem?

Brent Seales: It was Nat who suggested, well, you know, maybe we could just run a contest and the competitors could contribute in ways that, um, you know, you taking money for your research team wouldn't be able to contribute… I went back to Kentucky and talked with my research team, and it was actually really tricky to decide whether we were going to do this or not.

Going “open source” was a scary idea for Brent. Foundationally, the scientific method is meant to be collaborative. But, despite those aims, it’s also competitive. And there are incentives to be possessive of your discoveries.

MUSIC FADE

Brent was worried that he’d lose control of the project and waste years of work, not just for himself, but also for the PhD students in his lab.

Brent Seales: You can imagine that conversation where I come back and say, I'm really happy you're working on your PhD. I'm going to now make you compete with 2000 competitors worldwide who are going to be working on the same thing as you. So, good luck with your thesis defense, you know.

But another possible outcome was: it would be wonderful. With Nat Friedman and his investing partner Daniel Gross, their contest had the potential to bring hundreds, and even thousands of people, to focus on the problem. In a way, it was kind of the opposite of academia, which can be bottlenecked by lack of funding and time.

MUSIC: Bam, Bio Unit

Brent Seales: And eventually we, we being my research team, decided it was absolutely worth the risk. And everything that Nat said and did meant that he was going to be a great collaborator. So we just went ahead and took the risk and said, ‘we want to do this.’ … and things moved really quickly after that.

MUSIC SWELL AND FADE

BREAK

Nate Hegyi: Hey - Nate here. I wanted to let you know that our second ever Outside/In mug just dropped. It features an original illustration of an almost magical species… the Mexican salamander, also known as the axolotl.

Because here at Outside/In, we like to axolotl questions. [slowly]

If you want one – and you want to support journalism and public radio while you’re at it – head to outsideinradio.org/donate.

And thank you. So. Much.

It was the Ides of March, 2023, and Youssef Mohamed Nader was online.

MUSIC: Picaroo, Blue Dot Sessions

Youssef’s Egyptian, but he was working on his masters degree in Berlin, Germany.

Youssef Nader: At that time, I had finished, like, the, the fun part of the Masters. I just needed to write it up.

He’s now part of a research group which uses AI models to study the group behavior of fish and bees. But at that point in the semester, he was looking for a palate cleanser.

Youssef Nader: Yeah, that was like the less fun part of the thesis. So I like to have, like, a, um, a fun project on the side to, to work on.

He often browsed Kaggle, a website where people post AI puzzles and competitions. And something caught his eye: an announcement of something called The Vesuvius Challenge. “Resurrect an ancient library from the ashes of a volcano,” the post read.

The organizers of the competition had published Brent’s high-resolution scans from the synchrotron, made available to the world, for anyone to use. The task was: use machine learning models, or AI, to figure out how to read the Herculaneum Papyri. And it listed a Grand Prize as $700,000.

MUSIC FADE

This was different from any other challenge on Kaggle that Youssef had encountered. Everything about it was appealing.

Youssef Nader: … having access to historical data, working on a very hard problem, the aspect of like papyrus, which is, um, interesting for me as an Egyptian… my wife used to joke like, okay, it will be very cool if, like, you know, your Egyptian DNA sort of kicks in and, like, solves the papyrus problems.

Meanwhile, in California –

Arefeh Sherafati: Yes, I’m Arefeh Sherafati.

Arefeh Sherafati was working as a postdoc in a lab in San Francisco.

Arefeh Sherafati: Working at the intersection of neuroscience and artificial intelligence.

Arefeh had spent time in medical settings, studying CT scans, the very same technology used to scan the scrolls. So it made sense when a friend reached out about the Vesuvius Challenge and asked her to join his team.

Arefeh Sherafati: Yeah… it wasn't hard to convince me to work on it.

Her friend warned her: this is ambitious. It’s going to be like a second job. But like Youssef –

Arefeh Sherafati: The idea, I mean, there’s nothing more interesting to me, personally. To think that this is the only library from antiquity that's there, but we can't read it and… it might actually be the right time for us to attempt to read those … scrolls that they wrote, uh, two millennia ago. It's just that mind-boggling…

MUSIC: Fact Checkers (Instrumental Version), Xavy Rusan

The Vesuvius Challenge was structured very intentionally.

The idea was to bring that open source approach to the challenge of the papyri, so there were plenty of incentives to share data instead of hoard it. For example, there were lots of incremental prizes awarded throughout the process – and that way, even if people didn’t make it ALL THE WAY to the grand prize, which would take nine months, they’d still be rewarded – in cash – for participating even a little bit.

Actually, the very first one was an “Open Source Prize.” $2500 bucks, awarded to competitors who built stuff and released it publicly.

And whenever a contestant won a prize, under the rules of the competition, they had to share their methods and data with the rest of the community.

People could work alone or join up in teams. By the end of the competition, there were 1,249 teams, and a total of over 25,000 submissions for all the prizes.

MUSIC OUT

One of the scrolls they’d be working with, if you unrolled it, would be about 13 meters long. It's not meant to be opened vertically, like a medieval "Hear ye, hear ye" announcement. Instead, it would have been unfurled horizontally, like columns of a newspaper laid out on a long ticker tape – but again, all rolled up.

Julian Schilliger: That kind of looks like a tree stump if you just slice it and you have those yearly rings of the tree. Um, but instead of circular, it's a spiral. And this spiral represents the surface of the papyrus.

That’s Julian Schilliger. He’s another Vesuvius Challenge participant. At the time of the announcement, he was a masters student studying robotics in Switzerland.

The first major step of the process was figuring out where the surface of the papyrus actually was, which meant literally tracing the spiral inside the scan. This is a process which needs to be basically pixel perfect – or, that is, voxel perfect. Julian got pretty good at this.

Julian Schilliger: For the process there, you, you have this this spiral and you somehow have to track it. It's not always very obvious to the human eye either where this spiral exactly is positioned in this 3D data… And when you trace it over multiple different layers... in this, this tree stump, so to speak, then you can extract the surface and virtually unroll this scroll. That would be the first step.

The next major task was identifying the writing on the page – aka, “ink detection.” Here’s Arefeh.

Arefeh Sherafati: When you have a CT scan of your body, you can see the contrast, like you can see your bone… you can see organs… So you don't need sophisticated machine learning models… The doctor can just look at it.

But on most of the scrolls, there’s no contrast between the black ink and the black paper. So, instead, they had to look for morphological differences, like density or texture.

Arefeh Sherafati: How a surface of the glass is different from, like, a fabric. They just feel different. They look different. It could be geometrical differences. It could be bumps.

The task was to train their AI models to detect that barely-detectable ink. They started with small scraps of the scroll that had fallen off, where writing was much more visible.

Contestants would zoom in, sometimes down to the pixel, and label the data: this is ink, this is not-ink. Then you give the AI something new and see if it can do it on its own.

Youssef Nader: It was also about making sure that the AI has like this… room to disagree. So even if I tell, hey, this is this is for example… this looks like a P, it's like, no, this is a Phi and you like, missed a spot … having like this ability to kind of argue back, um, kind of gives like authenticity that the model is not just memorizing and, you know, hallucinating.

MUSIC: mosaik, bomull

It wasn’t long before thousands of people were working on virtually unwrapping the scrolls. For Brent, the computer scientist who spent two decades on his virtual unwrapping technique, this was a big change.

Brent Seales: Well, I mean, I have a very robust research group and have had for, for an academic setting, um, 6 or 8 undergraduates who are always interested, a postdoc, several staff members, three PhD students. It's actually big by academic standards… But I realized that I didn't really know what big was.

When Brent logged onto the contest’s Discord, he might see 500 people online, at any given time, talking about the project, from Australia, Brazil, China, the US.

The vibe on the community Discord, by the way, was pretty raucous and joyful,

Julian Schilliger: Oh yeah, of course.

Julian told me. Like, there were lots of memes.

Julian Schilliger: … if someone did something really cool, um, the emoji that we would use would be a hot flame or, um, an erupting volcano…

The burrito emoji also saw a lot of use on the Discord. One contestant even restored an old CT scanner to experiment with, and one day, as a joke –

Julian Schilliger: Someone also scanned a burrito instead of a scroll because they kind of look similar, I guess… The community is vibrant… You always have someone to talk to, to share your your new findings… If you're part of this, you don't feel alone.

MUSIC SWELL AND OUT

This kind of camaraderie and information-sharing led to big leaps, just as the organizers had hoped. Like when one contestant identified a crackly textural pattern to the ink – he shared it with the entire competition. He called it a “crackle signal.” Here’s Arefeh.

Arefeh Sherafati: And that was just the breakthrough everyone needed to be that, oh my God, it seems like there's actually… morphological difference that you might actually be able to see with the naked eye… And I got so good at it that I think I can just totally recognize the handwriting of the scribe who wrote these… and everything about those letters, basically.

MUSIC: Engine, Blue Dot Sessions

By October, seven months in, things were starting to change very quickly. One of the progress prizes was called the “First Letters” prize, awarded to the first person to identify a word.

But remember, this was in ancient Greek – there’s no spaces between the words, so it was difficult to know when they’d actually identified a word.

Youssef Nader: I kept, like, going all over crazy ideas, okay… maybe the letters start here or here or here, and then try to find words…

And yet, though he didn’t know what the word WAS until later, Youssef was one of two contestants to generate an image in which the same word was readable. And that first word was…

Youssef Nader: They saw the image and they were like oh! This is the word purple.

“Purple.”

MUSIC: Chris Zabriskie, Your Journey is Resuming Now

Federica Nicolardi: So the first word was this, πορφύραc, porphúra, or it's a form of perfume in Greek, which means purple. It can be the color or also the material.

That’s Federica Nicolardi again, the papyrologist we heard from earlier. She was also one of the judges on the Vesuvius Challenge. In that moment, Federica wasn’t wowed by the single word “purple” – which she explained is neither common nor completely rare, and it didn’t necessarily tell her much about the subject of the rest of the scroll. But it was still cool, and the word could just have easily been a filler word, like “and” or “the.”

But along with the word, Youssef’s model had generated five columns of text – a huge achievement.

MUSIC: Chris Zabriskie, Your Journey is Resuming Now

Federica Nicolardi: Yeah, it was crazy. I remember the first time, uh, Brent showed me an image. I was like, uh, so can I, can can I be happy about it? Is this real, or is there any chance that it is a fake or something? … and he said ‘yes.’

MUSIC FADE

After the First Letters prize, it was a grueling last couple months to the final deadline.

To be eligible for the grand prize, contestants would need to submit 4 passages of 140 characters each.

By the end, Youssef ended up forming a team with a couple people – including the other person who identified the word “purple” and with Julian, the Swiss robotics student. And Youssef had developed an iterative approach where he trained a consecutive series of AI models, each one trained on the predictions of the last.

Youssef Mohamed Nader: The AI makes predictions. I take these predictions, clean them up a little bit, give them to a new AI model to train… the new AI model finds more ink. I use this ink to train a new AI model. The new AI model finds more ink, and just you know, rinse and repeat … maybe more than 15 times between the first letters and the grand prize.

The deadline was midnight on New Year’s Eve.

MUSIC IN: audio_adac74d083

They missed a lot of the holidays.

Arefeh Sherafati: We lost a lot of sleep.

They set programs to run while they slept.

Arefeh Sherafati: Crazy.

Sometimes in Berlin, Youssef wouldn’t see the sun for days.

Youssef Nader: It’s like complete darkness. But it was really, really fun.

Arefeh Sherafati: I felt like my brain was not stopping.

MUSIC FADE

Arefeh Sherafati: We submitted our results, I think maybe, less than half an hour before the deadline and just too much adrenaline. I couldn't sleep after that. So it's just really staring. Okay, what just happened?

MUSIC: Arian Vale, Rhodia Syn stem, Blue Dot Session

And then they waited.

Arefeh was catching up on sleep, and reflecting on how time she’d just spent studying the handwriting of a scribe who lived two thousand years ago.

Arefeh Sherafati: It was really emotional...

There was one moment she remembers in particular – looking hard enough and long enough at a string of letters to realize she was looking at the root of the word “theory.”

Arefeh Sherafati: And I was almost in tears because all my life I loved math. I never spoke Greek, but to know I was, like, among the first people, maybe, to set eyes on these, like, unread texts… it connects you to all those people, like thousands of years ago who thought about these words in a philosophy context. It was really, really powerful.

MUSIC OUT

Finally, after about a month, they found out the results Out of 18 grand prize submissions, Arefeh’s team were runners up, and they had won fifty grand. Youssef and Julian’s team had won the grand prize, $700,000.

Youssef Nader: We were really thrilled and almost in disbelief. I think it took us like a couple of days… for it to sink in… I remember texting Julian like a couple of days later, like, ‘do you realize we won?!’ It hadn’t really sunk in.

MUSIC: Synthesized Dreams, Young Community

“After 2000 years, we can finally read the scrolls,” tweeted Nat Friedman.

So, after all that, what does the scroll say? In a way, this might sound a little anticlimactic.

MUSIC PAUSE

Papyrologists are still interpreting it.

MUSIC RESUME

But they do know a couple things. The winning submission included 15 columns of about 160 total in the scroll. They actually don’t even know the title yet, because that’s usually written at the very end, at the most interior, protected part of the papyrus.

But they do know it’s a work of Epicurean philosophy. In this scroll, it talks a lot about sight, taste, knowledge, music. In fact, the word that appears most often so far is pleasure.

MUSIC SWELL AND OUT

So, in a way, the work has just begun. There are hundreds more scrolls out there in the Herculaneum collection. And this “virtual unwrapping” technique can be applied to a lot more stuff. Even to objects like mummies, whose wrappings sometimes had writing on them as well.

And as for Brent, the computer scientist who’s been developing this decade for decades, he’s now joined by thousands more people, who are now personally invested in the story of the scrolls. When he reflects on his old fear of losing control and credit for unlocking the scrolls – he tries to put it in perspective.

Brent Seales: You know, sometimes, um, those instincts are right. But a lot of times they're the exact opposite of what you really want. Sometimes I still think, you know, ‘what happens if, you know, I, I don't get the credit I think I deserve?’ And in my life experience, the answer to that is, is absolutely nothing. It's going to be okay.

After everything, it’s not about getting credit. It’s not about money – though, admittedly, all that stuff is nice, and obviously makes a big difference in life. These scrolls are part of a broader human story. Brent says that no one “owns” the scrolls. They belong to everyone.

Brent Seales: I've always known that once we start reading reliably 3, 4, 500 things, nobody's going to keep going back and saying, oh, you remember this guy from 2009, right? I shouldn't even expect that. What they're going to say is: ‘we have a new work. It's Livy's History of Rome. We never had it before. This is amazing. Right? And that's the payback and that's what I want.

MUSIC: Jakarta Riddim, Konrad OldMoney

Nate Hegyi: Alright! The Vesuvius Challenge is not over – right Justine?

Justine Paradis: It is not over! They’ve announced lots of new prizes. Their community goal is to read 90% of four of the Herculaneum Scrolls.

Nate Hegyi: We’ll put a link in our show notes, in case you want to check it out. We’ll also share links to pictures of the scrolls and visualizations of the process of “virtual unwrapping.”

Justine Paradis: Thank you to everyone who spoke with me for this episode. I want to emphasize that we just talked to a few of the competitors, but this was such a group achievement. Shout out to the people we didn’t hear from in this episode – including Louis Schlessinger, who was runner up for the grand prize alongside Arefeh Sherafati, and Luke Farritor, who also found the word “purple” and was on the Grand Prize-winning team alongside Youssef and Julian.

Nate Hegyi: We’ve got another special thanks this week, to an eagle-eared listener. George wrote in from Salt Lake City, Utah to point out an error in our recent episode about aluminum. In 1943, when the Allies bombed a German cryolite factory, all but one of the 180 bombers returned safely. But we inadvertently reported the opposite. We erroneously said that all but one were DESTROYED.

Justine Paradis: Amazing how a single word can totally flip the meaning of a sentence.

Nate Hegyi: I know right?

Justine Paradis: That episode has now been corrected.

Nate Hegyi: This episode of Outside/In was reported, produced and mixed by Justine Paradis, and edited by Taylor Quimby. Our staff also includes Felix Poon.

NHPR’s Director of Podcasts is Rebecca Lavoie.

Music in this episode came from Silver Maple, Xavy Rusan, bomull, Young Community, Bio Unit, Konrad OldMoney, Chris Zabriski, and Blue Dot Sessions.

Outside/In is a production of NHPR.