Never Bring a Sledgehammer to a Scalpel Fight

When a Harvard professor accidentally let Gypsy Moths loose in the 1860s, he didn’t realize he was releasing a scourge that would plague New England forests for more than a century. Nothing could stop the moths except a controversial method of wildlife management called biocontrol. It’s the scientific version of “fighting fire with fire”: eradicate an invasive species by introducing another invasive species. Since then, there have been lots of biocontrol success stories, but also a few disastrous failures. In this episode, we ask whether biocontrol is the best--maybe the only way--to combat invasives, or if it’s just an example of scientific hubris.

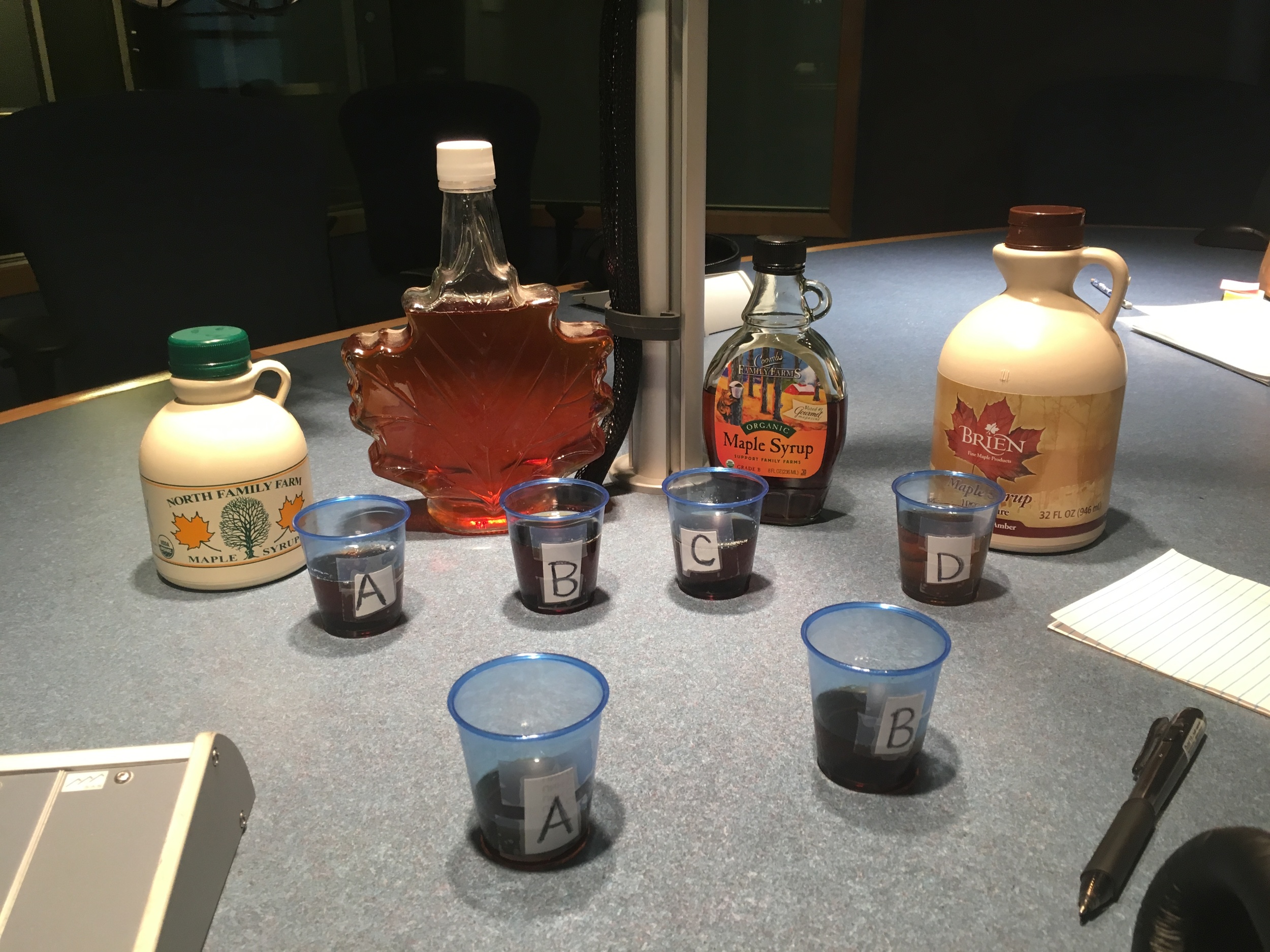

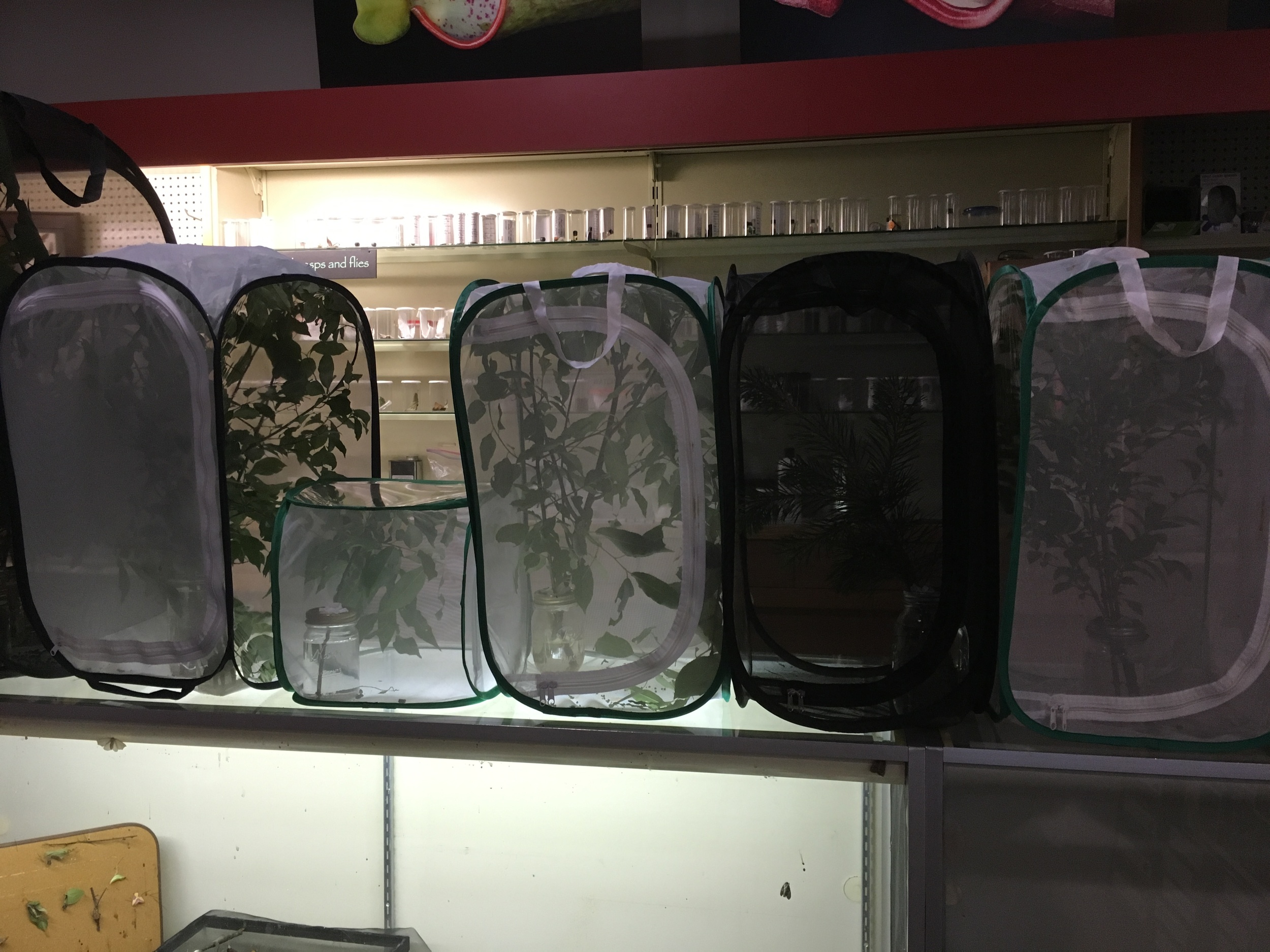

Show of hands. Say you had a swarm of wood-boring beetles and you wanted to get rid of them. These beetles were never supposed to be here—they were brought in from Asia, unintentionally. Would a good way to rid yourself of them be to introduce a parasitic wasp, also from Asia, that would probably beat the beetles down?

Anyone?

We have been hard-wired to recognize this as folly. Exhibit A: The Simpsons.

In this episode, Bart accidentally introduces a pair of invasive Bolivian tree lizards into the town of Springfield. The local bird club is horrified at first, but then delighted, when it turns out the lizards’ preferred food is pigeon meat.

This idea—using nature to fight nature—is called classical biological control or biocontrol. And examples abound of when it’s gone horribly wrong.

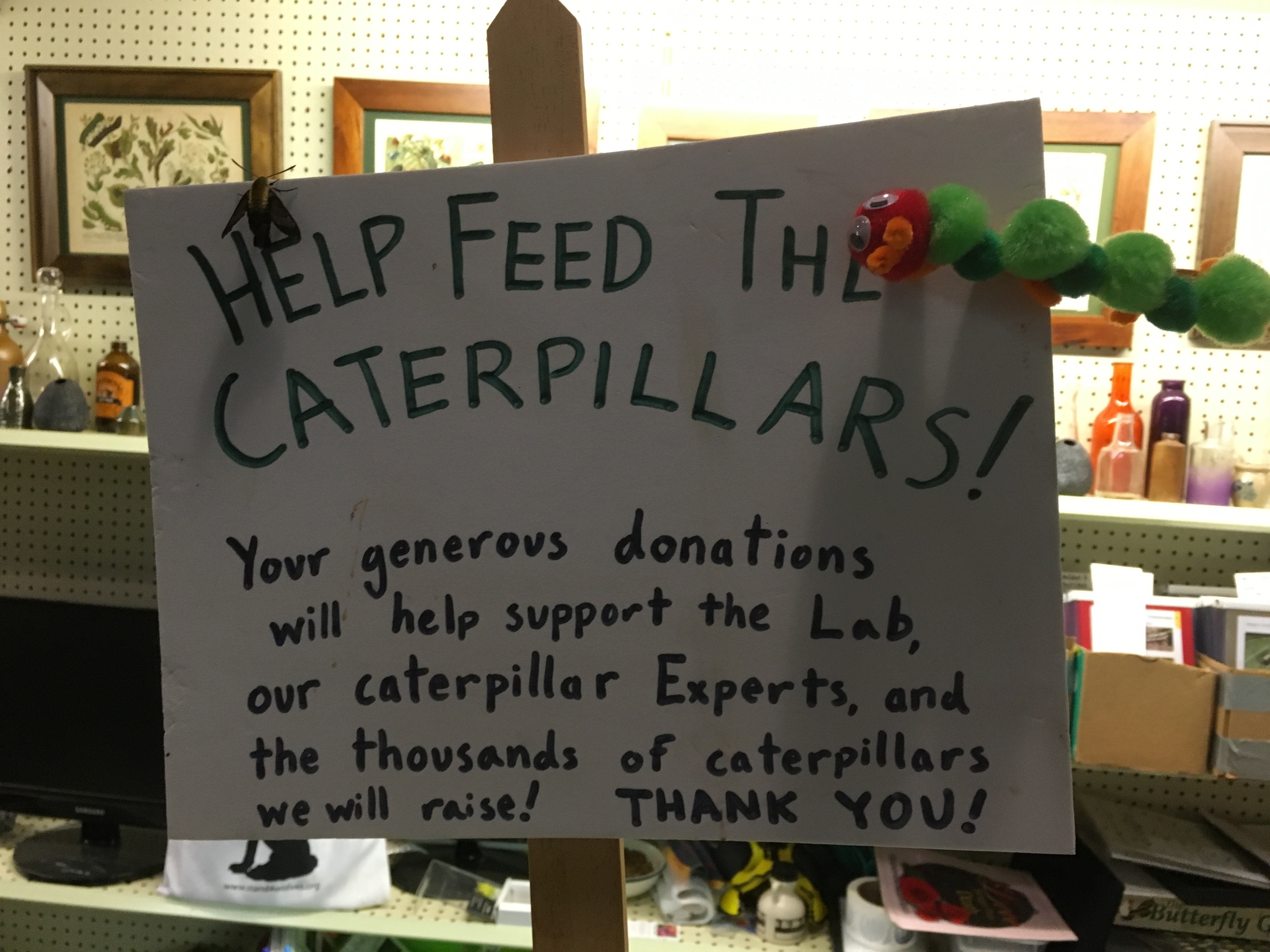

For instance, this spring, New England experienced the worst outbreak of invasive gypsy moth caterpillars in more than 30 years. The last time the caterpillars were this bad the forest they denuded (they eat leaves) was an area bigger than the states of Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts combined. This year, you could see their impact from space.

We’ve been trying to control the gypsy moths for over 100 years. In 1906, the US Department of Agriculture released a parasitic fly—Compsilura concinnata—in hopes that it would kill the gypsy moth caterpillars. But this fly was something of a sledgehammer. Yeah, it killed some gypsy moths, but it also killed lots of other kinds of moths, too. Two hundred types of moths, to be precise. Among the fly’s unsuspecting victims were the so-called giant silkworm moths—luna moths, cecropia moths, royal walnut moths—which are almost totally benign and often staggeringly beautiful. One study found that the fly killed as many as 80 percent of cecropia moths, which, at about the size of your hand, is North America’s biggest moth. For all that, it didn’t have a lasting impact on the gypsy moths–they tempered the attack well.

a lovely little luna.

This story is not unique—introduced mongooses have decimated Hawaii’s native birds, and cane toads have caused a decline in Australia’s adorable northern quoll populations—and they have served as a cautionary tale (or as a cult classic documentary for high-school stoners) for decades now. They help flesh out the narrative of humanity as giant-sized children, stomping about in nature, wielding a power whose consequences we are far too simple to understand.

And yet, we still use biocontrol. The first bullet on the USDA’s biocontrol website asserts “it is easy and safe to use.”

Will we never learn? Actually, biocontrol advocates argue, we already have. What’s more, even with all the horror stories, biocontrol has a better record than we think.

Consider again the case of the gypsy moth. The parasitic fly was no good. But twice in the 20th century—first in 1910 and 1911, and then again in 1985 and 1986—scientists tried to introduce a fungus, Entomophaga maimaiga, that they believed would kill gypsy moths. Neither introduction survived, but then mysteriously, in 1989, the fungus took off in Connecticut. It’s now credited with reducing the population of leaf-munching caterpillars by 85 percent, as long as it's wet enough for the fungus to thrive.

But here’s the kicker, the fungus works like a scalpel; there’s almost no collateral damage. Of 1,500 dead insects collected in an area where the fungus was present—representing 53 species—only two individual (non-gypsy) moths had been killed by the fungus, according to a field study.

What’s more, despite the skepticism evident in the writers’ room at The Simpsons, the history of biocontrol is largely a history of scalpels, not sledgehammers.

Two recent studies have asked the question: how safe is biocontrol? One assesses insects introduced to kill other insects, and the second looked at insects introduced to eat weeds. Both found that when biocontrol is conducted by scientists, it has a pretty darn good safety record, with more than 99 percent of introductions having no significant impact on any “non-target” species.

#GypsyMoths causing destruction throughout eastern forests. https://t.co/I29gQl8eka pic.twitter.com/KCBfyIZ1Rg

— Our Amazing Planet (@OAPlanet) July 23, 2016

That doesn’t mean they all work. Somewhere between 50 and 70 percent of introduced biocontrol agents fail to establish themselves at all. Only 10 percent fully control the pest they target.

Still, there are some smashing success stories out there. Purple loosestrife, a plant that clogs up streams and rivers and has been declared a “noxious” invasive weed by 23 states, has been tamed by four species of European loosestrife beetles, which have been seen to eat up to 90 percent of the weed in some spots. In the 70s, several countries in Africa started to see massive crop failures of cassava, a plant that feeds hundreds of millions of people all over the world. Scientists found a tiny wasp which very specifically targeted the bugs that were eating the cassava, and today crop damage from the so-called cassava mealybug has declined by 90 percent.

Further, the entire practice is being much more carefully regulated these days. Biocontrol introductions in the U.S. have been slowing down since the 80s, and in 2000 the USDA began requiring biocontrol projects to go through a permitting process that includes testing to ensure that impacts to native species will be minimal.

The idea that biocontrol is a poorly understood tool being wielded by irresponsible scientists is “kind of an old fashioned view actually,” says Cornell entomologist Ann Hajek, “Those dangerous introductions aren’t being done anymore.”

So why do we only hear stories of biocontrol gone horribly wrong? Because it’s a better story, one that fit the narrative of the early environmental movement: we’re trashing the planet.

In the early days, biocontrol was believed to be an environmentally friendly alternative to pesticides. So in 1983 when an entomologist named Francis Howarth assembled in one place all of the horror stories of biocontrol gone wrong it was “a man bites dog story,” says Russell Messing from the Kauai Agricultural Research station in Hawaii. He says bashing on biocontrol became a “fad” in ecology. “A lot of people jumped on board, and there were a lot of papers published, and even some reputations made, I think,” he says.

Howarth is retired, but the torch of biocontrol skepticism today is carried by Dan Simberloff, at the University of Tennessee. Simberloff says that even in its more strictly regulated form, modern biocontrol still risks driving rare native species into extinction.

As his example, he points to efforts to control the emerald ash borer, a beetle currently destroying ash trees all over the eastern United States. There are more than 100 species of native “jewel beetles” and he says “some of them are so rare that they’re only collected by entomologists once every decade, if that.” His argument is that USDA scientists could not have possibly checked all of those myriad beetles to be sure they wouldn’t be preyed upon by the parasitic wasps currently being released to combat the emerald ash borer. We could annihilate a species of native beetle, and not even realize it for years.

But what then is one to do about the invasive emerald ash borer, which has killed more than 90 percent of the ash trees it infests (and as go those ash trees, so too go the 44 species of native insects that depend on ash trees to survive)?

“I don’t really know what to do,” Simberloff says.

Indeed.

“In the absence of biocontrol there is no solution,” says biocontrol researcher Joe Elkington, at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, “I mean, there’s no solution.”

Outside/In was produced this week by:

Sam Evans-Brown, Maureen McMurray, Taylor Quimby, Molly Donahue, Jimmy Gutierrez, & Logan Shannon

Theme music by Breakmaster Cylinder

Photos of Sam are by Greta Rybus unless otherwise noted.