The curious case of the missing extinctions

When it comes to protecting the biodiversity of Planet Earth, there is perhaps no greater failure than extinction. Thankfully, only a few dozen species have been officially declared extinct by the US Fish and Wildlife Service in the half century since the passage of the Endangered Species Act.

But, hold on. Aren’t we in the middle of the sixth mass extinction? Shouldn’t the list of extinct species be… way longer?

Well, yeah. Maybe.

Producer Taylor Quimby sets out to understand why it’s so difficult to officially declare an animal extinct. Along the way, he compares rare animals to missing socks, finds a way to invoke Lizzo during an investigation of an endangered species of crabgrass, and learns about the disturbing concept of “dark extinctions.”

Editor's Note: This episode was first published in October 2022. Since then, the US Fish and Wildlife Service officially delisted 21 of 23 proposed species due to extinction. The ivory-billed woodpecker was not one of them.

Featuring Sharon Marino, Arne Mooers, Sean O’Brien, Bill Nichols, and Wes Knapp.

Editor’s Note: A previous version of this episode misspelled the name of NatureServe, and inexplicably joked about it. We apologize for the error.

“Birds & Nature” Marble, Charles C; Higley, William Kerr (1896) Via American Museum of Natural History Library & Biodiversity Heritage Library

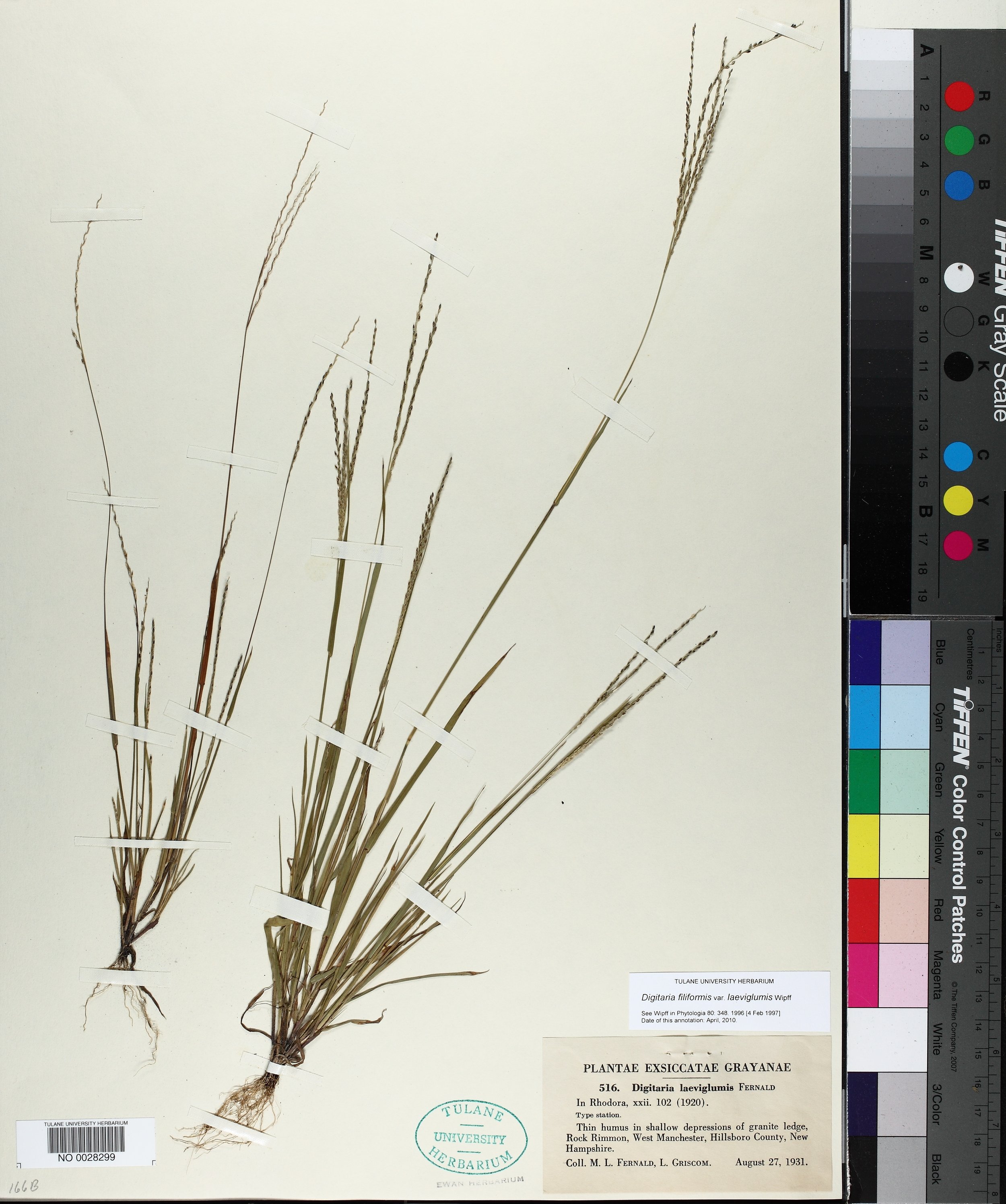

Digitaria filiformis var. laeviglumis (Fernald) Wipff SEINet Portal Network. 2022. Accessed on October 13.

Botanist Bill Nichols looks out over Rock Rimmon, in Manchester, New Hampshire.

Nichols calls Rock Rimmon a “botanical hotspot.” It was once home to the now extinct smooth slender crabgrass.

Love Outside/In? You’ll love the (free) Outside/In newsletter! Sign-up here.

SUPPORT

Outside/In is made possible with listener support. Click here to become a sustaining member of Outside/In.

Follow Outside/In on Instagram or Twitter, or join our private discussion group on Facebook

LINKS

Check out this 2005 feature from the CBS Sunday Morning archives: In search of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker…

…and this one from 60 minutes, also from 2005, pulled from the archive and rebroadcast after the proposed delisting.

Nate’s favorite ivory-billed story came from NPR, and featured songwriter Sufjan Stevens.

Watch the US Fish and Wildlife Service virtual public meeting about the proposed delisting of the ivory-billed woodpecker on January 26th, 2022.

Read this 2016 paper that outlines, among other things, the consequences of being waitlisted under the ESA: “Taxa, petitioning agency, and lawsuits affect time spent awaiting listing under the US Endangered Species Act.”

From Simon Fraser University, “Lost or extinct? Study finds the existence of 562 animal species remains uncertain.”

More on the unknown status of Cambodia’s national mammal, the kouprey.

Wes Knapps’ paper on “Dark Extinctions” among vascular plants in the continental United States and Canada.

Read about the extinction of smooth slender crabgrass, the first documented extinction in New Hampshire.

Evening pickleball at Rock Rimmon Park in Manchester, New Hampshire

CREDITS

Host: Nate Hegyi

Reported and produced by: Taylor Quimby

Mixer: Taylor Quimby

Editing by Rebecca Lavoie and Nate Hegyi, with help from Justine Paradis, Felix Poon, and Jessica Hunt.

Rebecca Lavoie is our Executive Producer

Special thanks to Noah Greenwald, Jonathan Reichard, Tom Martin, and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Music for this episode by Silver Maple and Blue Dot Sessions.

Our theme music is by Breakmaster Cylinder.

Outside/In is a production of New Hampshire Public Radio

If you’ve got a question for the Outside/In[box] hotline, give us a call! We’re always looking for rabbit holes to dive down into. Leave us a voicemail at: 1-844-GO-OTTER (844-466-8837). Don’t forget to leave a number so we can call you back.

Audio Transcript

Note: Episodes of Outside/In are made as pieces of audio, and some context and nuance may be lost on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors.

Taylor Quimby: Nate.

Nate Hegyi: Taylor.

Taylor Quimby: Listen to this.

Nate Hegyi: I hear static.

Taylor Quimby: Wait for it.

[Chirp sound]

Taylor Quimby: Hear that?

Nate Hegyi: Yeah. I hear that.

[Chirp sound]

Taylor Quimby: So that honk… is a recording of The Ivory Billed Woodpecker - captured in 1935 by the guy who actually founded the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology.

Nate Hegyi: Oh really! I love that. I used to go on their website to listen to bird sounds.

Taylor Quimby: It’s a huge bird, as big as your forearm, with a head like a little pickaxe, and big perfectly round eyes.

It was so striking, people gave it a nickname…

Nate Hegyi: I know the name.

Taylor Quimby: You’ve heard this?

Nate Hegyi: They called it “The Lord God Bird”. I listen to Sufjan Stevens

Taylor Quimby: Hmm, the Lord god bird.

[bird SFX and religious chanting rises and then ends abruptly]

BUT…

President Nixon: We have passed new laws to the protect the environment…

By the time President Nixon signed the Endangered Species Act in 1973 …

President Nixon: … and we have mobilized the power of public concern…

Taylor Quimby: … There hadn’t been an officially recognized sighting in the United States in almost 30 years.

President Nixon: …But there is still much to be done.

Nate Hegyi: Uh oh. That’s not good.

[mux sneaks in]

Taylor Quimby: When The Simpsons first aired in 1989?

Bart Simpson: Cowabunga!

It had been almost fifty years since the last officially recognized sighting.

Homer Simpson: Doh!

Taylor Quimby: Now, there were lots of reported sightings…

News anchor: Have you seen this bird?

… but never anything universally accepted by ornithologists.

Reporter: The only picture is grainy…

Just disputed photographs…

Reporter.. And horribly out of focus.

Tantalizing but inconclusive recordings…

Scientist: This is an interesting sound, recorded on January…

And more often than not, a little controversy.

Witness: The bird dropped in from above the canopy, into the channel and headed straight towards me…

Nate Hegyi: Kind of sounds like the Bigfoot of the bird world.

Taylor Quimby: People literally say, the sasquatch…

Nate Hegyi: Really?

Taylor Quimby: … of birds, yeah.

Birder: I spent 241 days out here in the swamps.

Reporter: And you didn’t get a picture?

Birder: No.

Reporter: So this is harder than you thought.

Birder: This is harder than we all thought.

Reporter:

[mux fades]

Taylor Quimby: So… , in 2021… 77 years since the last universally accepted sighting, the US Fish and Wildlife Service made a proposal…

To finally declare the Ivory Billed Woodpecker - along with 23 other species - officially - extinct.

News clip: John Yang has more now on what experts are calling an accelerated crisis.

News clip: Other species on the list, the Bachman’s warbler songbirds, and a group of birds and bats found only in the pacific islands…

Taylor Quimby: I know. But Nate… even though these extinctions are terribly tragic, you know what was thinking when I heard about these 23 species?

Nate Hegyi: What?

Taylor Quimby: I was thinking… Only 23?

[mux]

Because If it took 77 years for us to declare one woodpecker extinct….

How many other species are already gone too?

[theme in]

Nate Hegyi: that’s a good question.

Taylor Quimby: It’s a dark question.

[clip montage]

Wes Knapp: There’s this whole field I call dark extinctions.

Sean O’Brien: It feels like the number should be bigger.

[somber mux]

Nate Hegyi: This is Outside/In. I’m Nate Hegyi.

Scientists say we’re in the midst of the planet’s 6th mass extinction…. That Earth’s biodiversity is on the precipice.

Taylor Quimby: But if that’s the case…. why don’t we hear about extinction more often?

Bill Nichols: We’ve had four extinctions in New England already. This will be the fifth that nobody talks about either likely.

Nate Hegyi: Today, producer Taylor Quimby is sharing the story of a hunt. A hunt to find out if the low numbers of declared extinctions is a conservation success story… Or just the tip of an exceptionally depressing iceberg.

[mux fades]

Taylor Quimby: Nate, question: were you a Hardy Boys fan growing up?

Nate Hegyi: No. I grew up in the 1990s, not the 1950s.

Taylor Quimby: The Hardy Boys are still popular!

Nate Hegyi: Are they?

Taylor Quimby: I read them when I was a kid in the ‘80s.

Nate Hegyi: I never read the Hardy Boys, I wasn’t a Hardy Boys fan.

Taylor Quimby: Alright, well… whatever. To get in the mood for this episode I’ve been calling this “The Mystery of the Missing Extinctions.”

And this mystery starts, as many Hardy Boys adventures do, with a report from the United Nations.

Nate Hegyi: …what?

CNN clip: An alarming new report just released by the UN that says roughly one million species are on the verge of extinction.

Taylor Quimby: So this was in 2019 - and the report was DIRE. One million species on the brink.

News clip: That includes more than 40% of amphibian species, and more than a third of marine mammals.

And what’s worse - most of this crisis can be traced back to to do with human activity.

News clip: from climate change, overfishing, and pollution.

But here’s the thing - aside from the woodpecker I mentioned at the top, name me five species that have gone extinct in your lifetime.

Nate Hegyi: That have gone extinct in my lifetime? Oh man. One second. Um.. Hmm. Wait no, give me time, this is just a recording, I’ve got time to think. Well, did…?

That rhinoceros. That one rhinoceros.

[mux swells]

Taylor Quimby: So my point is that the most famous modern extinctions died off years ago - the dodo. The passenger pigeon.

And by the way, the Northern White Rhino that you’re thinking about is actually only a subspecies. And that was on its way out since we were kids.

Nate Hegyi: It was.

Taylor Quimby: So it seems to me - that if things are this bad, we should be hearing about extinctions all the time.

Nate Hegyi: So where do you start trying to close that gap? Like if this were a missing persons case - where would you go to first?

Taylor Quimby: Well, to the to the people that actually track endangered species here in the US - the US fish and wildlife service.

Sharon Marino: You know, 99% of all listed species are still with us today that have been added to the list.

Taylor Quimby: So this is Sharon Marino. She’s the Northeast’s Assistant regional director for Ecological Services at the US Fish and Wildlife service.

Nate Hegyi: Oh that is a very bureaucratic title.

Taylor Quimby: They all are, they all are.

Sharon Marino: In terms of number of species that we've actually delisted, we've delisted 52 species and down listed. So that means going from an endangered status to a threatened status, 56 species. So I think there are lot of successes we can share, iconic species like the bald eagle and the peregrine falcon.

Nate Hegyi: So from a percentage standpoint - this law, and the folks who are enforcing it, are really knocking it out of the park.

Taylor Quimby: Yes and no.

There are more than one-hundred thousand species of plants and animals here in the United States.

But the US Fish and Wildlife Service is only able to study about 50 a year, to decide whether they should be listed under the ESA or not.

Nate Hegyi: So there’s an endangered species list… and there’s a possibly endangered species waitlist.

Taylor Quimby: And the waitlist is loooong.

[mux]

Taylor Quimby: The Center for Biological Diversity, a serious advocate for endangered species, did a study in the early 2000s that documented 42 species they say went extinct while on the waitlist, and another 29 species that went extinct without ever having entered any sort of formal process at all.

Nate Hegyi: Well, there’s your missing extinctions then. That’s twice as many as are officially declared, right?

Taylor Quimby: It is, and the story gets deeper because that is just here in the US.

[mux]

So to widen my search, Interpol style, which I don’t think the Hardy Boys ever did…

Nate Hegyi: I don’t think they ever got Interpol involved.

Taylor Quimby: Uh, no. I wound up reaching out to a guy named Arne Mooers [ARE-nah MOW-ers], a professor of biodiversity at Simon Fraser University, in Vancouver.

He told me about the global version of the Endangered species list, which is called the IUCN Red list - and their definition of extinction is pretty strict. By the way.

Arne Mooers: So the formal and depressing definition of extinction is “a taxon, which is a species, is presumed extinct when exhaustive surveys in known and or expected habitat at appropriate times, time of day, seasonal, annual throughout its historic range, have failed to record an individual.

So it’s like exhaustive, appropriate, et cetera, et cetera.

Taylor Quimby: Now, because it's global, the Red List has way more species designated as extinct: more than 900 in total.

But Arne Mooers agrees with me: if things are as bad as scientists are saying they are, even 900 is too low.

Arne Mooers: Of course, there's a big difference between, you know, at risk of extinction and already extinct. But you'd still think they'd be closer. Given that, as you say, we're in this middle of this crisis, which means that things should be popping off, you know, continually. Right.

And that's why we dug into this and realized that, yeah, that's partly because there is this, this huge kind of backlog of lost species that may or may not be extinct.

[mux]

Nate Hegyi: Wait, so yeah, that’s what I said earlier! Was like, lost species, can’t find them, doesn’t mean that they’re extinct? Just means we can’t find them!

Taylor Quimby: Exactly, they are lost to us. So - you remember how the ivory-billed woodpecker hadn’t had an official sighting in over 70 years?

Nate Hegyi: Mm-hmm.

Taylor Quimby: That might be considered a “lost species.” Well, Arne and his collaborators decided to see how many other terrestrial vertebrate species - so not counting bugs, or plants, or fish - which ones also haven’t been seen in a really long time.

Arne Mooers: We said, what are we going to use? 10 years, 50 year? Every species is different. And we said, well, we're just going to arbitrarily say 50 years and take a look. And there's, you know, 562 species that haven't been seen in over 50 years. And that's what we reported.

So that's 562 terrestrial vertebrate species that have not been seen in at least 50 years. And that's almost twice as many as the ones that have officially been declared extinct.

Nate Hegyi: So we’re either really bad at finding these species, or they’re extinct.

Taylor Quimby: Well, they’re like missing socks. Some of them are truly gone forever and we’ll never get them back, and some of them are buried under your bed.

Nate Hegyi: Yeah, they’re orphaned somewhere deep inside the bowels of your closet.

Taylor Quimby: Extinct animals are like socks, is the moral of this story.

Listen, the most shocking thing from my conversation with Arne, is that you know, a lot of these animals are small things like voles or mice, hard to track. But some of them are fairly large, important animals.

So for example, there are only five egg-laying mammals - that we know of - on the entire planet.

One of them is… can you guess, Nate?

Nate Hegyi: Uhh, uhh… Platypus!

Taylor Quimby: And the other four are species of these kind of hedge-hoggy looking animals called echidnas.

Arne Mooers: And several of those echidnas haven't been seen for 40 or 50 years either… you'd think people would want to know about those guys because they are so rare.

Taylor Quimby: Another really wild example is called the kouprey - ever heard of it?

Nate Hegyi: No.

Taylor Quimby: So it is a big cow with these beautiful curved horns kind of like crescent moons, and you’ll find depictions of it everywhere in Cambodia - it’s on statues, it’s on stamps - even their national football team is nicknamed the Koupreys!

Arne Mooers: It's Cambodia's national mammal. Right? So it's like your bald eagle kind of thing. It's like the national anthem or our beaver. It hasn't been seen since 1969. Wow.

[mux]

And you're like, well, how… How does that work?

Taylor Quimby: It's a cow!

Arne Mooers: It's huge. Yeah.

[mux swells and fades]

Nate Hegyi: So I think the question I have now is… why is it so hard to declare something extinct? Is it just inertia? Lack of resources?

Taylor Quimby: Let me ask you a question in the Socratic style… what proof do you have that aliens do not exist?

Nate Hegyi: I don’t have any proof of that.

Sean O’Brien: Because it's so hard to essentially prove a negative. Right. If you weren't in the picture frame right now, that doesn't mean you're not at home. It just means I can't see you.

So this, by the way, is a guy named Sean O’Brien - CEO of a non-profit called Nature Serv.

Sean O’Brien: Nature Serve is nature's tech firm, and we are the source of data on threatened and imperiled species across the United States and Canada.

Taylor Quimby: And Nature Serve exists because of problem number two: endangered species don’t respect borders.

Sean O'Brien: So when we talk about New Hampshire and Vermont - if you look at the those data from those two states, they’re not really comparable. You have to go through all sorts of gymnastics to make them match up.

Taylor Quimby: So Nature Serv consolidates all of the data from state agencies, and academia, and data from citizen science platforms like iBird or iNaturalist - and then, calculates all that info to recommend whether such-and-such species should be labeled critically endangered, or just threatened, or species of least concern.

Nate Hegyi: This sounds a little bit like a commercial.

Taylor Quimby: Truly, but let me just say they are a way more important part of the process than I would have guessed going into this story. It’s much harder to get an accurate picture of biodiversity in parts of the world that don’t have systems like this.

Nate Hegyi: Fair enough.

But, even a group like Nature Serv can’t help with Problem number three: Sometimes, there isn’t much data to pull.

Either because there aren’t many people studying a particular animal, or because that animal lives in a super hard-to-get-to place - a jungle, or on the side of a remote mountain range, or in a dense swamp.

Nate Hegyi: Think about how hard it would be to hike to the top of the himalayas to see a snow leopard.

Taylor Quimby: Problem number four: We don’t even always agree on what is and isn’t a species -

Sean O’Brien: Genetics may help us figure some this out going forward, but it’s a non-trivial problem.

…or have enough scientists to comb through all the ones we do agree on.

Sean O'Brien: The vast majority of beetles have… don't have names. You know, they may have been seen and photographed or, you know, museum specimens, but there's not enough beetle experts in the world to describe all the beetles in anybody's lifetime because there's just so many.

So what all that means is that some of the places with the richest biodiversity are also the places where we have no idea what we’re losing.

Sean O'Brien: And so and there's also this desire to not have things be declared extinct because there's enough habitat and there's enough space out there that maybe the ivory-billed woodpecker is somewhere or some parakeet is still somewhere.

And if you’ve got even a shred of hope that something is still out there, you might not want to declare it extinct because being on the endangered species list affords special habitat protections, and helps raise funds for conservation -

Nate Hegyi: But being extinct offers diddly-squat.

Exactly.

[mux]

So let’s try and understand this through the lens of the Ivory-billed woodpecker.

First of all, just because there hasn’t been an official sighting doesn’t mean it’s not there.

Nate Hegyi: Can’t prove a negative.

Taylor Quimby: Its habitat, if it does still exist, is now restricted to southern swamps that have to be navigated by boat.

Nate Hegyi: Hard to do the research.

Taylor Quimby: Another challenge: There have been lots of unconfirmed sightings - but what determines confirmation?

Nate Hegyi: Right! So confirmation to me might not be confirmation to you.

Taylor Quimby: But here’s the thing: The ivory-billed woodpecker may be the most sought after of these lost species. Millions of dollars and thousands of hours of time have been spent trying to find it.

If there is one species we should be able to confirm one way or another?

Nate Hegyi: It should be this one.

Taylor Quimby: And yet.

USFWS employee: With that we’re going to our next registered commenter, John Williams…

Nate - you remember when at the beginning of this story I said that the US Fish and Wildlife Service was PROPOSING that we put the ivory-billed woodpecker on the extinction list?

Nate Hegyi: Uh huh.

Taylor Quimby: Well, before a proposed delisting takes place - the ESA requires a public comment period.

And let me tell you - people have thoughts.

Public commenter 1: Since the year 2000, 8 expeditions have searched for the Ivory-billed woodpecker and have reported encounters.

Public commenter 2: The ivory-billed woodpecker has been deemed extinct by some people at least several times in the past 120 years, and each time has defied those who would write it off.

Public commenter 3: The species status assessment upon which this proposal is based is very light.

Sooooo, in January 2022….

Public commenter 4: This is a premature proposal.

Person…

Public commenter 5: It’s premature.

After person…

Public commenter 6: The proposal is premature.

And I’m not talking quacks and conspiracy theorists, I’m talking respected ornithologists and birders and zoologists and naturalists…

Public commenter 7: I think the delisting is premature. I think there’s ample evidence to show it’s still out there.

All came out to say that IT’S TOO SOON to call the ivory-billed woodpecker extinct.

Public commenter 8: This ivory-billed woodpecker controversy is a, uh. It’s a moral issue. It’s not just about a bird.

Nate Hegyi: So was it… Did the US Fish and Wildlife Service reverse the decision?

Taylor Quimby: They delayed it. So this hearing was in January, and then this summer they put the decision off for an additional six months

Nate Hegyi: Classic. Classic federal move. We’re not going to reverse. Let’s all just take a breather here.

Taylor Quimby: And get this - in August, a group called Project Principalis - which sounds like a CIA group or something - put out some very far away drone footage of what they say is an ivory-billed woodpecker.

Some scientists are convinced - others have called the footage “laughable”...

Nate Hegyi: Mean!

Taylor Quimby: And a policy guy with the Center for Biological Diversity, which is usually all about getting animals onto the endangered species list said - "there are better and more reliable photographs of Sasquatch floating around the internet than these images of this supposed ivory-billed woodpecker."

Nate Hegyi: So the controversy continues.

Taylor Quimby: It does.

Public commenter 9: I think a word I’ve been hearing a lot is premature. That the delisting is premature, everything we’re doing is premature. But the last credible sighting has been, 80 years ago, something like that. It’s been awhile.

It’s been plenty of time to search through all these mystical swamps, and bogs and wetlands… to find a very large and supposedly very loud woodpecker.

At some point or another, you’ve got to accept that it’s extinct.

[mux]

Taylor Quimby: One thing I’ve discovered, Nate, is that it’s easy to care about a big beautiful bird like the ivory-billed woodpecker… But if we’re going to address this crisis, we’re going to have to get people to care about the things that aren’t so charismatic…

And I bet it’s a lot harder than you might think.

Nate Hegyi: That’s coming up in just a minute - but first, a little PSA. This is a story that, in a way, is about what we take for granted. What we choose to pay attention to, and what we choose to ignore.

And I just want to say, if you really value this show - don’t take it for granted. Sure we occasionally get sponsors, but don’t be fooled - this is a public radio operation, and we rely on your donations to fund our work.

If you can’t afford to donate a couple bucks, share the show, rate it and review it - all that good stuff - but if you can donate, do it. There’s a link in the show notes - and thanks.

BREAK

Nate Hegyi: Welcome back to Outside/In, I’m Nate Hegyi - here with producer and extinction detective Taylor Quimby.

[car sound]

Taylor Quimby: So this spring I got a tip about a possible extinction taking place - Not in a remote swamp, or one of the Galapagos islands - but in a city park about ten minutes from my apartment.

Nate Hegyi: In Manchester? New Hampshire?

Taylor Quimby: Yeah. So to learn more I drove out to Rock Rimmon Park to meet up with Bill Nichols…

Taylor Quimby: Nice to meet you Bill.

… State Botanist with the NH Natural Heritage Bureau.

Taylor Quimby: Is there a history to rock ribbed park that I should know about? I mean, is this like a historical place of any kind?

Bill Nichols: It's a botanical it's well known to be a botanical hotspot.

[mux]

Bill Nichols: So oddly enough, despite the heavy recreation use and and other factors that are somewhat detrimental to plant species, the there's been ten state endangered and state threatened plant species that have been collected here over the last 120 years.

And just so you know, this is like an actual city park. There’s a playground, and a bunch of brand new pickle-ball courts…

Taylor Quimby: Everybody plays pickleball now.

Bill Nichols: During the summer months, all the courts are taken.

But towering over the courts is this big stony tooth that juts up 150 feet out over Manchester’s west side.

And if you climb the short but steep trail to the top, you can see the whole city. It’s pretty cool - but also, people treat it like a dump.

Bill Nichols: Have you been to the summit?

Taylor Quimby: Uhh, no.

Bill Nichols: Because once we get up there, there's graffiti everywhere, there's more trash in some places, the glass is replacing the natural soil in the crevices. So and because of all that, five of the ten state endangered or state threatened plant species that have been documented here, we believe are extirpated from the site.

So extirpated, for folks who don’t know, is like… locally extinct.

Nate Hegyi: Yup, gone from one area. Yeah. It could be gone from New Hampshire but it could be in Maine.

Taylor Quimby: Exactly. Now Bill and I are here because one of the rare plants that isn’t here anymore, that’s gone. … may have been the only population of its kind left on the planet. Which is different.

And that plant is called….

Bill Nichols: Smooth-slender crabgrass, Digitaria filiformis variety laeviglumis.

Taylor Quimby: Whoa, whoa, whoa. Slow down, one syllable at a time.

Bill Nichols: The genus Crabgrass is Digitaria. The slender crabgrass is Digitaria filiformis, and the variety of crabgrass that we believe very likely has gone extinct is variety laeviglumis. So Digitaria filiformis variety laeviglumis.

[mux]

Nate Hegyi: I mean to be fair, even our transcription software had a hard time with that. It says “digitally a former slave of Loomis.

Taylor Quimby: Here it says “lava gloomism.”

Nate Hegyi: That sounds like an emotional state.

Taylor Quimby: That sounds like a plant in Mordor. So here’s the conundrum. Bill thinks this might be the first extinction in New Hampshire on record.

But when I met up with him, I still had to keep all this news under wraps because he was still waiting on DNA tests to make sure that the old crabgrass collected here was genetically distinct from some other novel crabgrasses recently collected in Mexico and Venezuela.

Nate Hegyi: So we need to press pause here. Are we talking about crabgrass, the stuff that you see, that weed that sprouts out from sidewalk cracks and drives lawn people bananas?

Taylor Quimby: Oh yeah.

Bill Nichols: The only difference, the main difference that separates smooth, slender crabgrass from the other three varieties in that complex is the spike. It is glamorous. There's no pubescent. There aren't any hairs on the spike. Litt The other three varieties are here, have a hairy spikelet.

[pause]

Nate Hegyi: Okay, so Taylor… I need to ask an honest question. This is no offense to Bill…

Taylor Quimby: Listen I know where this is going, you have to ask it - I asked the same question.

Nate Hegyi: But given how many, possibly much more important species are on the brink… does it really matter if this very particular kind of crabgrass goes extinct?

Taylor Quimby: Well, before I answer, it gets worse.

Because it’s been over 90 years since this thing was last seen, when a botanist collected samples from this very rock on August 27th, 1931.

Taylor Quimby: And about what size is a collection in that case?

Bill Nichols: Well, on average, each one of those collections, 30 collections on the last eight was ever documented. They averaged three plants per sheet with fruit and roots. So it is clearly over collection. And it could have been an unintended one of the unintended consequences associated with that 30 collections on August 27, 1931. It could have played a role in the eventual extinction of smooth land and crabgrass at the site.

Taylor Quimby: Well, that must be deeply disappointing to think about as a botanist.

[mux]

Nate Hegyi: So this poor botanist, in 1931, could have inadvertently made this crabgrass extinct.

Taylor Quimby: Yeah.

Nate Hegyi: Grim, but again… even if it is a distinct species, how do you get your average person to care?

Because I think a lot of folks are one-hundred percent against extinction, but if you ask them for example they’re thinking about bumblebees, or pandas, or condors.

Taylor Quimby: Well I asked Bill that same question, and he pointed to wolves.

Bill Nichols: The extirpation of wolves and the extinction of the eastern cougar led to the white tailed deer. their population just took right off. That led to over browsing, which is having an impact on forest succession.

Taylor Quimby: Bill, I don't want to play the devil's advocate when it comes to saying that extinctions don't matter, because obviously they do. But, you know, when you're talking about, you know, extirpation of wolves from the landscape, you know, compare it to crabgrass, which I think most people are going to think… “crabgrass? Like, that's the stuff that I don't want on my lawn.”

Bill Nichols: It's much easier with cuddly mammals than it is with plants. Especially grass. And especially a crabgrass.

[mux]

Nate Hegyi: But it’s not like all crabgrass is going away, it’s a crabgrass that grows on one rock.

Taylor Quimby: I think the scale of those examples is totally totally off.

But Bill and others like to make this analogy:

Sean O’Brien: And the analogy is that, there are a lot of rivets on an airplane.

You take out a few of them and the plane’s fine. Literally nothing changes. Take out a few more, nothing changes. Take out a few more, nothing changes.

Sean O’Brien: But eventually the wing is going to fall off.

And then the thing crashes.

Sean O’Brien: But we don't know which rivet is the one that's going to cause the wing to fall off. And it's the same way with the biodiversity that's out there. And so, you know, the smooth, curly crabgrass may not be the one that causes the ecosystem in that park to go down, but it's one of the rivets in that ecosystem.

Taylor Quimby: The other piece that I’ll say is that, even if it didn’t matter! Isn’t there a moral case to be made?

Nate Hegyi: That’s the argument I’ve heard. Isn’t there a moral responsibility that if we know we can save something, shouldn’t we save it.

Taylor Quimby: But regardless, Bill is admittedly very pessimistic about the public reaction if this ends up getting declared extinct.

Bill Nichols: We have that the manuscript that will be published in one of the science journals. So the word would get out that way. There will be a press release associated with it. But then it be like other extinctions, particularly ones that aren't cuddling and fuzzy and charismatic.

Taylor Quimby: So it'll fizzle out.

Bill Nichols: It'll fizzle out, there's no question. It'll just be I mean, we've had four extinctions already in New England. And how widely are those four species names known to the public and to botanists even?

Taylor Quimby: I don't think I know them.

Bill Nichols: Who talks about those four species? this will be the fifth that eventually won’t be talked about either, likely.

[mux]

Taylor Quimby: So,what I didn’t realize when I was talking to Bill, is that even if nobody cares about the extinction of smooth slender crabgrass - documenting it still has purpose.

Wes Knapp: We didn't know what was extinct. And if you don't know it's extinct, you can't learn from it.

Alright, so this is Wes Knapp - he’s the chief botanist at Nature Serve and one of a growing number of folks studying extinction.

Wes Knapp: So there's this whole field I call dark extinctions, which are extinctions that happened and no-one knew about them.

Nate Hegyi: So an… undocumented extinction?

Taylor Quimby: Right - if a lost species is one we’re not sure about, a dark extinction is one we just neglected to pay attention to until after it was too late.

And Wes and his team have tracked down a number of these, that, like smooth slender crabgrass - were collected long ago and then put in a drawer somewhere and forgotten.

Wes Knapp: In 2020, I described and recognized this plant called the large flowered barber's buttons as being misinterpreted by science. It was thought to range from Pennsylvania all the way down to Tennessee, and then it was gone from western North Carolina. And I remember pulling up specimens of this plant from western North Carolina and saying, Oh, that is not the same plant that occurs in Pennsylvania. It was shockingly different because I knew the plants in Pennsylvania. And what we came to find out is that that plant from western North Carolina is now extinct, but it wasn't recognized as a distinct species until my work with collaborators. So we renamed the existing plants a new name, the beautiful barber's buttons, marshaling a polka to show that they were different and that that was a dark extinction that went undetected for 101 years. It was last collected in 1919.

Nate Hegyi: That’s a great name.

Taylor Quimby: Beautiful Barber’s Buttons?

Nate Hegyi: Yeah, I love that. It feels very antiquated. Barber’s buttons.

Taylor Quimby: But anyway, Wes and his team wound up finding a total of 65 vascular plant species - trees, shrubs, and actually mostly a bunch of herbs - that all went extinct.

And only 2 of them were had even been registered on the IUCN Red list of endangered species.

And it’s led him to realize that one of the biggest risk factors for plant extinctions are species that are only found in one place.

Wes Knapp: The 64% of all the extinct plants from the US and Canada were known from just a single site, So there's this horrible disproportion of plants that are going extinct that are known from extremely narrow geographic distributions.

[mux]

So yeah, maybe the crabgrass is just one rivet. But that missing rivet is also a clue so people like Wes can figure out how many other rivets are also gone.

And it’s not a small number.

[dial sounds]

So this summer, I got the heads up from Bill Nichols - the crabgrass guy -

Taylor Quimby: Hey, Bill. How's it going?

Bill Nichols: Good, thank you.

Taylor Quimby: Bill just got a DNA test, turns out, Smooth Slender Crabgrass is one-hundred percent it’s own extinct species.

Taylor Quimby: What's. How are you feeling? Are you, is this… Are you in a state of big relief, or are you in a state of, like, let down here? Where's your head at?

Bill Nichols: Definitely a sense of relief. And, you know, we've known we were pretty confident maybe in the last 15, 20 years that smooth landed crabgrass is likely extinct. But we just didn't have the data to declare that.

Nate Hegyi: It’s kind of weird to hear him say they could’ve said this 15, 20 years ago.

Taylor Quimby: And a few minutes later told me they definitely could’ve done it a couple years ago.

Bill Nichols: But it would have always bothered me that wait, there are possible next steps we could take to more confidently make that declaration. Why not do it? And that led to two additional years of research.

Nate Hegyi: Scientists man. I mean… is that really necessary?

Taylor Quimby: Bill is being meticulous for a reason.

Because deciding how to split species is one of the most divisive subjects in biological sciences.

Other scientists aren’t necessarily obligated to take him at his word.

Bill Nichols: People sometimes are reluctant to. It's like, oh, I have to learn a bunch of new names and I just don't want to adopt this. This is a phenomena called taxonomic inertia.

Taylor Quimby: And there are real ripple effects here - because even though it was too late for the smooth slender crabgrass, this project put a spotlight on another kind of rare and potentially endangered crabgrass in Florida that could still be saved. And this project put that on the road to maybe being listed.

Nate Hegyi: Oh, that’s cool!

Bill Nichols: Its story in and of itself. The story of the extinction of some Icelandic crabgrass could be a wake up call. You know we have lost our first native plant species to extinction. This wasn’t a natural processes that led to this extinction. This was directly related to human activity. So that’s important to let people know that’ shappened, so they can contemplate that and let it sit with them.

[mux]

[door SFX/mux]

Taylor Quimby: Man, it’s a beautiful night.

Taylor Quimby: So, since I live just down the road from Rock Rimmon.

Taylor Quimby: There’s legit like two dozen people playing pickleball right now.

I decided to drive over there and have a little ceremony.

Taylor Quimby: This looks like a good place. K, pulling up the list here.

I looked up the IUCN Red list, the global list of endangered species - and I filtered it for a category that doesn’t get talked about enough - “critically endangered, possibly extinct.”

And if there’s a moral to this story, it might be that we should be using this designation a lot more.

Taylor Quimby: Guess I’m gonna start at the top.

And I decided I’m going to read some of 1200 species on there. I started with the crabgrass - which we know is gone.

Taylor Quimby: Smooth slender crabgrass. Digitaria Lavagloomis.

And then started going through the rest. .

Taylor Quimby: Lord Howe Horn-Headed stick insect. Cornokenovia Australica.

Because if you never name the dead - nobody will remember them.

But if you don’t name the problem - you’ll never come up with a solution.

[Taylor read many, many, many names of possibly extinct animals as mux rises, until they start to overlap