The Ballad and the Flood

In Appalachia, Hurricane Helene was a thousand-year-flood. It flattened towns and forests, washed roads away, and killed hundreds.

But this story is not about the flood. It’s about what happened after.

A month after Hurricane Helene, our producer Justine Paradis visited Marshall, a tiny town in the Black Mountains of western North Carolina, a region renowned for its biodiversity, music, and art.

Josh Copus walking along the French Broad River in Marshall, North Carolina. Photo by Alex Barao.

She went to see what it really looks like on the ground in the wake of a disaster, and how people create systems to help each other. But what she found there wasn’t just a model of mutual aid: it was a glimpse of another way to live with one another.

Featuring Josh Copus, Becca Nicholson, Rachel Bennett, Steve Matlack, Keith Majeroni, and Ian Montgomery.

Appearances by Meredith Silver, Anna Thompson, Kenneth Satterfield, Reid Creswell, Jim Purkerson, Jazz Maltz, Melanie Risch, and Alexandra Barao.

Songs performed by Sheila Kay Adams, Analo Phillips, Leah Song and Chloe Smith of Rising Appalachia, and William Ritter.

SUPPORT

Outside/In is made possible with listener support. Click here to become a sustaining member.

Subscribe to our newsletter to get occasional emails about new show swag, call-outs for listener submissions, and other announcements.

Follow Outside/In on Instagram or X, or join our private discussion group on Facebook.

LINKS

An excerpt of “A Paradise Built in Hell” by Rebecca Solnit (quoted in this episode) is available on Lithub.

“You know our systems are broke when 5 gay DJs can bring 10k of supplies back before the national guard does.” (Them)

The folks behind the Instagram account @photosfromhelene find, clean, and share lost hurricane photos, aiming to reunite hurricane survivors with their photo memories.

A great essay on mutual aid by Jia Tolentino (The New Yorker)

CREDITS

Outside/In host: Nate Hegyi

Reported, written, produced, and mixed by Justine Paradis

Edited by Taylor Quimby

Our team also includes Felix Poon, Marina Henke, and Kate Dario.

NHPR’s Director of Podcasts is Rebecca Lavoie

Special thanks to the folks at Poder Emma and Collaborativa La Milpa in Asheville. Thanks also to Rural Organizing and Resilience (ROAR).

Music by Doctor Turtle, Guustaav, Cody High, Blue Dot Sessions, and Silver Maple.

Outside/In is a production of New Hampshire Public Radio.

If you’ve got a question for the Outside/Inbox hotline, give us a call! We’re always looking for rabbit holes to dive down. Leave us a voicemail at: 1-844-GO-OTTER (844-466-8837). Don’t forget to leave a number so we can call you back.

Audio Transcript

Note: Episodes of Outside/In are made as pieces of audio, and some context and nuance may be lost on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors.

Transcript: The Ballad and the Flood

Note: Episodes of Outside/In are made as pieces of audio, and some context and nuance may be lost on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors.

Nate Hegyi: There’s an old saying about the town of Marshall, North Carolina. It’s “one mile long, one street wide, sky-high, and hell deep.”

MUSIC: Doctor Turtle, That Guy’s Sky is Too High

Nate Hegyi: It’s nestled in the Black Mountains of southern Appalachia. It’s got a couple cafes. A flower shop. A courthouse… and an old jail.

Josh Copus: In 2016 I pushed all my chips in on Marshall.

Nate Hegyi: This is artist and entrepreneur Josh Copus.

Josh Copus: I bought a house out here, and I bought the Old Madison County Jail at a property auction with three friends for under 100,000 bucks. And it was the craziest thing that I’ve ever done.

MUSIC FADE

Nate Hegyi: The jail was exactly what you’d imagine. Metal bars, peeling paint, and a whole lot of history. There was even a local guy who escaped out the roof in the ‘90s.

Josh Copus: Yeah, Omar Lee Smith went through the roof in this room that we're sitting in right now… I actually found his hacksaw blades in the attic during the reno and called him up and said, hey, dude, come down here. I got something I think you want to see.’ …and he said, ‘where'd you find them?’ And I said, ‘they were in the attic.’ And he just said, ‘that's right where I left them.’

Nate Hegyi: Josh and his friends spent five years refurbishing the place. Now, it’s a boutique hotel and a restaurant, plus a music venue.

Josh Copus: Anyway, so Omar, like, towards the end of the project, he came in here and he's looking around and he just looked at me and he said, ‘Josh, I just gotta say it, man. I really love what you've done with the place.’

MUSIC: Within These Walls, Guustavv

Nate Hegyi: But then, in September 2024, came Hurricane Helene. As the storm traveled North, it poured into the Black Mountains. The French Broad River surged over its banks, then, over the railroad tracks. According to Josh’s flood gauge, it crested at 27 feet.

Josh Copus: I was standing on the courthouse, and I just, I watched all the windows shatter in my friend's coffee shop… and then just all the chairs just floated out the windows and down the street.

MUSIC FADE

Nate Hegyi: During the storm, every single building downtown flooded almost to the second story. And when it was over, the entire town of Marshall was covered in a thick layer of mud and trash.

Josh Copus: In that moment, like I’m a really optimistic person but in that moment, I was like we’re finished.

MUSIC: St Augustine, Rhodia RingSyn stem

Josh Copus: … like, you don't know how to act, you don't know how to be like, I just remember being like, like, do I make breakfast? Do I eat like, what? What am I doing? … How do I live? What is my purpose? Who am I? … I guess I'll just go to the town. And then everyone else kind of just had that same idea, and then we were just all here. And then people were like, I guess we just start cleaning up. And so that's what happened. We did.

Nate Hegyi: This is Outside/In. I’m Nate Hegyi. A month after Hurricane Helene, our producer Justine Paradis spent four days in and around the town of Marshall. She went to see what it really looks like on the ground in the wake of a disaster.

Meredith Silver: We’re getting some taste of what’s possible. There’s something really liberating about that.

Nate Hegyi: How people create systems to help each other.

Ian Montgomery: It’s been the most rewarding month of my life. It’s renewed my faith in humanity.

Nate Hegyi: But what she found wasn’t just a model of mutual aid. It was a glimpse into another way to live with each other.

Josh Copus: It was like through that process that I kind of was like, you know what, like, this town is worth saving, because the town is not the buildings or the stuff. It's the people, and the people are still here.

MUSIC POST AND FADE

Josh Copus: Great. Come on upstairs… So the water came to, like, here… it went to this top step, but it didn’t go in.

Justine Paradis: By the time I arrived in Marshall, it’d been four weeks since Helene. And by that point, the bottom floor of the jail hotel was a full-on construction zone. But the second floor was like a time capsule. Unscathed.

Josh Copus: Like when you walk in this room…

Justine Paradis: Bed is made.

Josh Copus: The beds are made. There’s a serious surrealness to that.

Justine Paradis: Josh Copus is a person who looks comfortable rolling up his sleeves. He’s a potter. Been throwing clay since he was a kid. But after the flood, it was hard to know where to start.

Josh Copus: It was hard. Like, I didn’t talk to my mom for days.

Justine Paradis: In a lot of towns, there was no potable water, and roads were impassable or just plain gone.

Josh Copus: She was like, I know you’re smart and you’re good… but she was also like, I don't know if you’re alive.

Justine Paradis: For thousands of people, the only thing they could think to do was to leave the house and start to find each other – often by walking and hitchhiking, knocking on doors, leaving notes. In Marshall, people grabbed shovels and just started digging out. Hauling mud out of the buildings in buckets and wheelbarrows. And soon after, people started singing.

Sheila Kay Adams [singing in OMJH after storm]: It’s been a year since last we met. And we may never meet again. I have struggled to forget but the struggle is in vain.

Justine Paradis: This is Sheila Kay Adams, singing in a video Josh posted to Instagram a little over a week after the flood. She’s sitting on a wooden bench in the jail, hands clasped, eyes closed. You can hear a flurry of construction activity in the background.

Sheila Kay Adams [singing]: His bright smile haunts me still in the midnight on the sea.

Justine Paradis: Sheila Kay is a seventh generation ballad singer. Before the flood, she and other singers would gather at the Old Marshall Jail Hotel once a month for something called a ballad-swap.

Josh Copus: So, the ballad tradition is an oral tradition. And it’s done how we say ‘knee to knee…’ You sing a verse, then you sing it back, then they add a verse, and you sing it back.

Justine Paradis: These are spiritual songs and stuff like murder ballads: stories told in song, typically sung a capella, by single voices. They go back to the first Scots-Irish settlers who came to North America.

Josh Copus: Appalachia was an extremely isolated place, and so the songs were preserved here, in some extents, better than where they originated from.

Justine Paradis: So this impromptu performance in the jailhouse wasn’t just a diversion. It was also a statement.

Josh Copus: They're powerful… like I watched Sheila Kay sing a song in a pile of garbage that used to be my restaurant and I don’t know any person who could hear that and not cry… like it was our loss in this moment but it was also just like this generational outpouring of like who we are as a people. It was one of the most powerful things that I've ever seen.

Sheila Kay Adams [finishing song]: His bright smile haunts me still.

Justine Paradis: That day, Josh and Sheila Kay promised each other they would sing there again soon.

Josh Copus: We made a commitment to each other to do the ballad swap before the end of the month.

MUSIC: Traveling Upstream, Cody High

Justine Paradis: When I decided to travel to North Carolina, it was because I wanted to understand mutual aid during disaster recovery, to see what it looks like up close.

The basic idea of mutual aid is simple: neighbors helping neighbors. It can look all kinds of ways. It’s a practice of voluntary, free help – when people self-organize to do stuff like pass out food, coordinate a clean-up effort, or deliver free firewood.

Disasters are inherently chaotic. But something that makes mutual aid operations so remarkable is how sophisticated they can be.

MUSIC FADE

[Nanostead ambi]

Keith Majeroni: Go to that table there to get your PPE. Unless you want to work at the decon station. They were looking for volunteers there.

Justine Paradis: A couple miles up the hill from Marshall sits a dusty workyard. The HQ of a construction company which builds tiny houses called Nanostead – get it, homestead, but nano? In the weeks after the hurricane, it became a hub of mutual aid for a specific purpose: to be the staging point for the Marshall clean-up operation.

At Nanostead, they suit volunteers up in protective gear, send them downtown to dig mud, and then bring them back for a hot meal and maybe a little music at the end of the day.

Becca Nicholson: We have more, I put some of the jackets in here too… We have more, I just didn’t want to give you all of it. But anyway, they’re all like 2XL… but you know…

Justine Paradis: This is the PPE department: a bunch of tables and bins under a tent with stacks and stacks of rubber gloves, bins and bins of workboots, Tyvek suits, and respirators. It’s being run by Becca Nicholson, who lives a mile or so down the road and is right now psyched about a new shipment of high-visibility, or high viz, construction gear.

Becca Nicholson: It’s the little things, you know. High viz pants. We’re all so stoked about it.

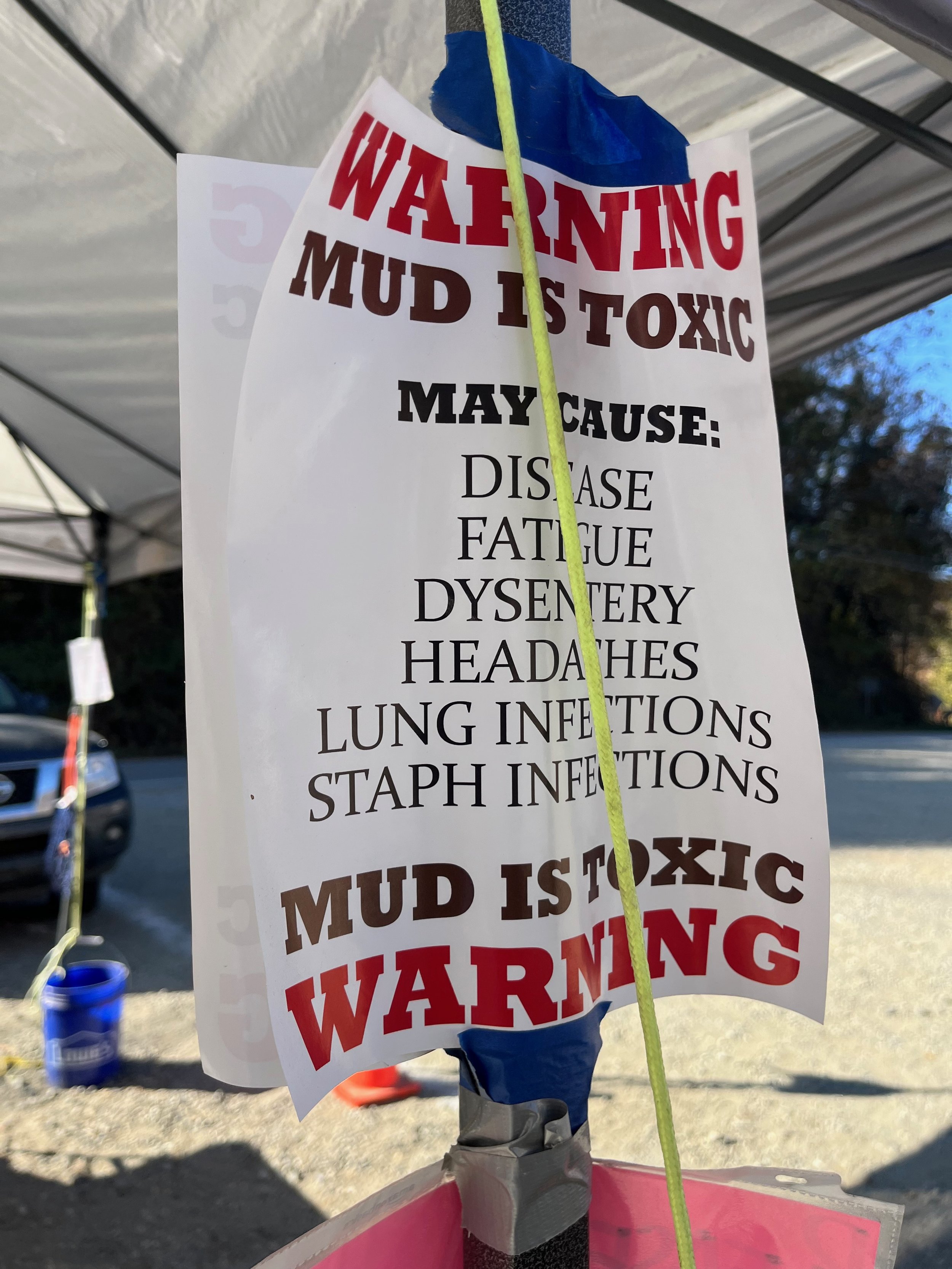

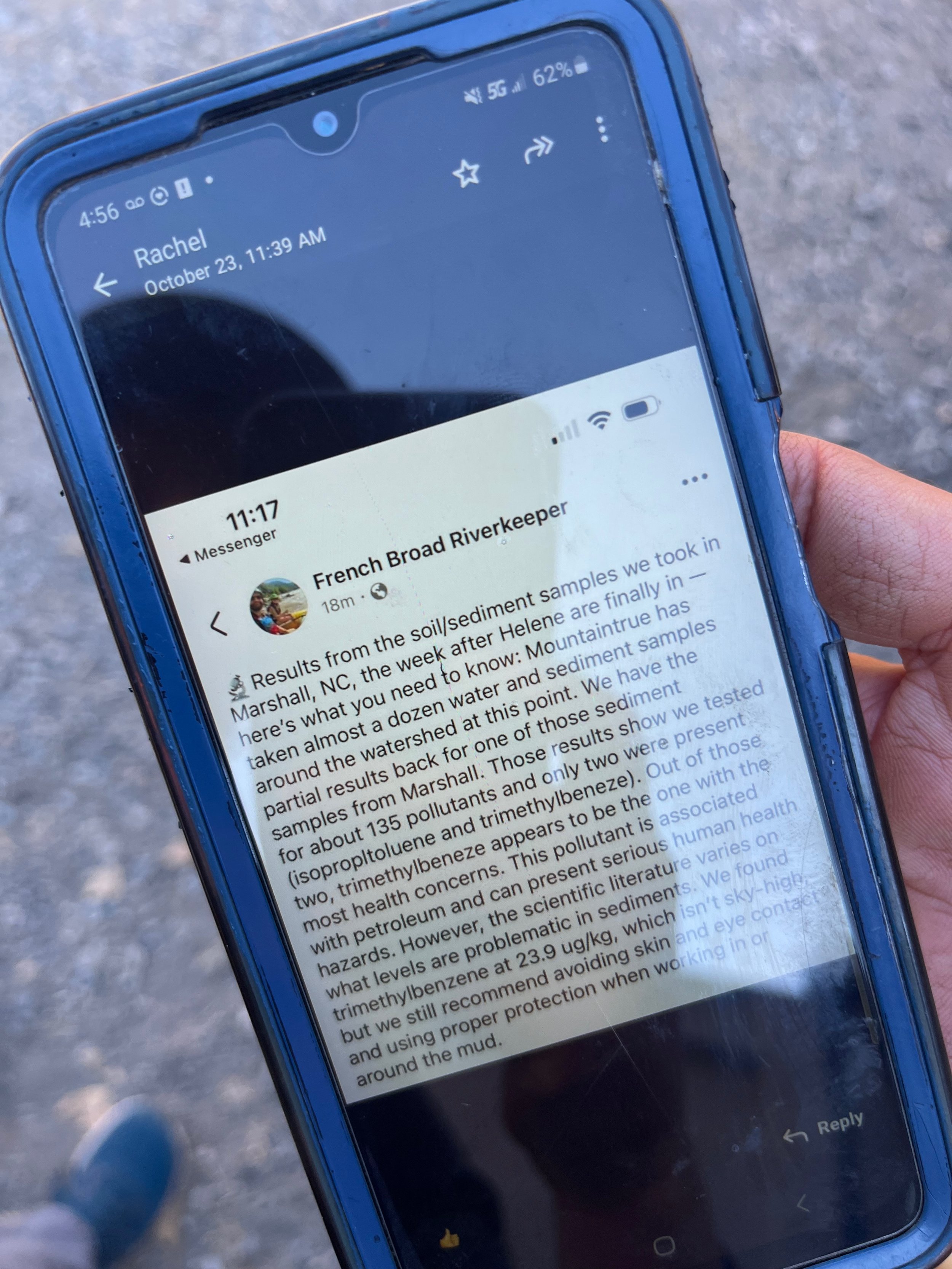

Becca explains clean-ups like the one happening in Marshall aren’t just hard work. They’re also dangerous. Floodwater and leftover mud can contain sewage, contaminants, and all kinds of chemicals.

Becca Nicholson: Myself personally, the first few days there were a ton of fumes, so many fumes. So I had like a three day migraine the few days after the storm.

Justine Paradis: From what?

Becca Nicholson: Um, just like, um, I, like, walked down to as far as I could go to the end of Main Street before the water came up and there were just huge propane tanks spewing their contents, oil tanks spewing their contents like floating down the river.

MUSIC: Kirkus, Blue Dot Sessions

Justine Paradis: The way Nanostead Hub came to be is in the days after the storm, the folks who run the tiny house company decided to grill hot dogs for their neighbors, and quickly, people just started gathering there and bringing supplies. Meanwhile, downtown, people had already started digging out the mud. The problem was…

Becca Nicholson: No one was wearing gloves, no one was wearing, like, hardly anyone was wearing any masks or anything. And I was, I kind of had this like, ‘oh gosh, like, this is bad.’ And I came here to drop off supplies one day and I was like, oh, I feel like they need help.

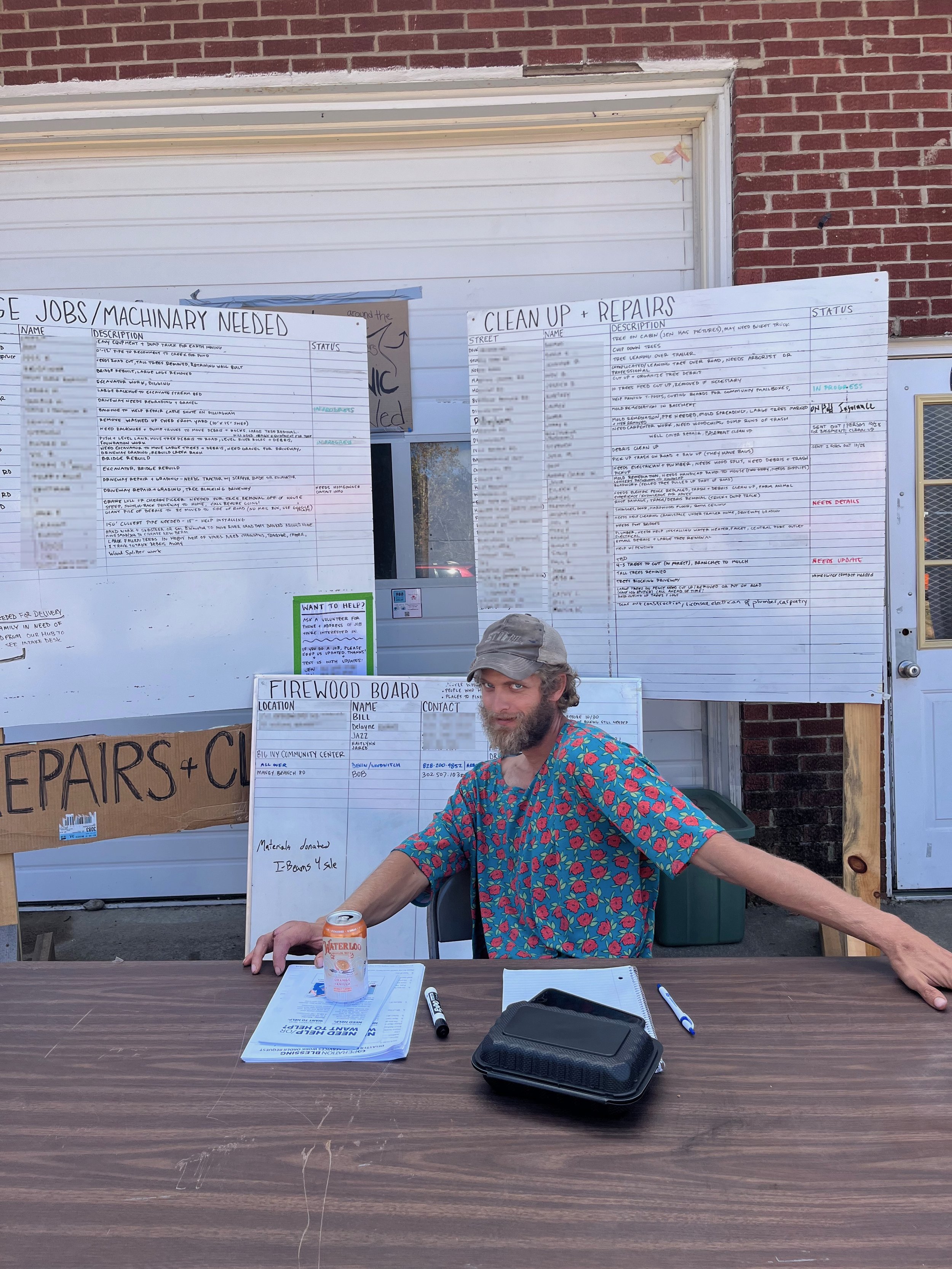

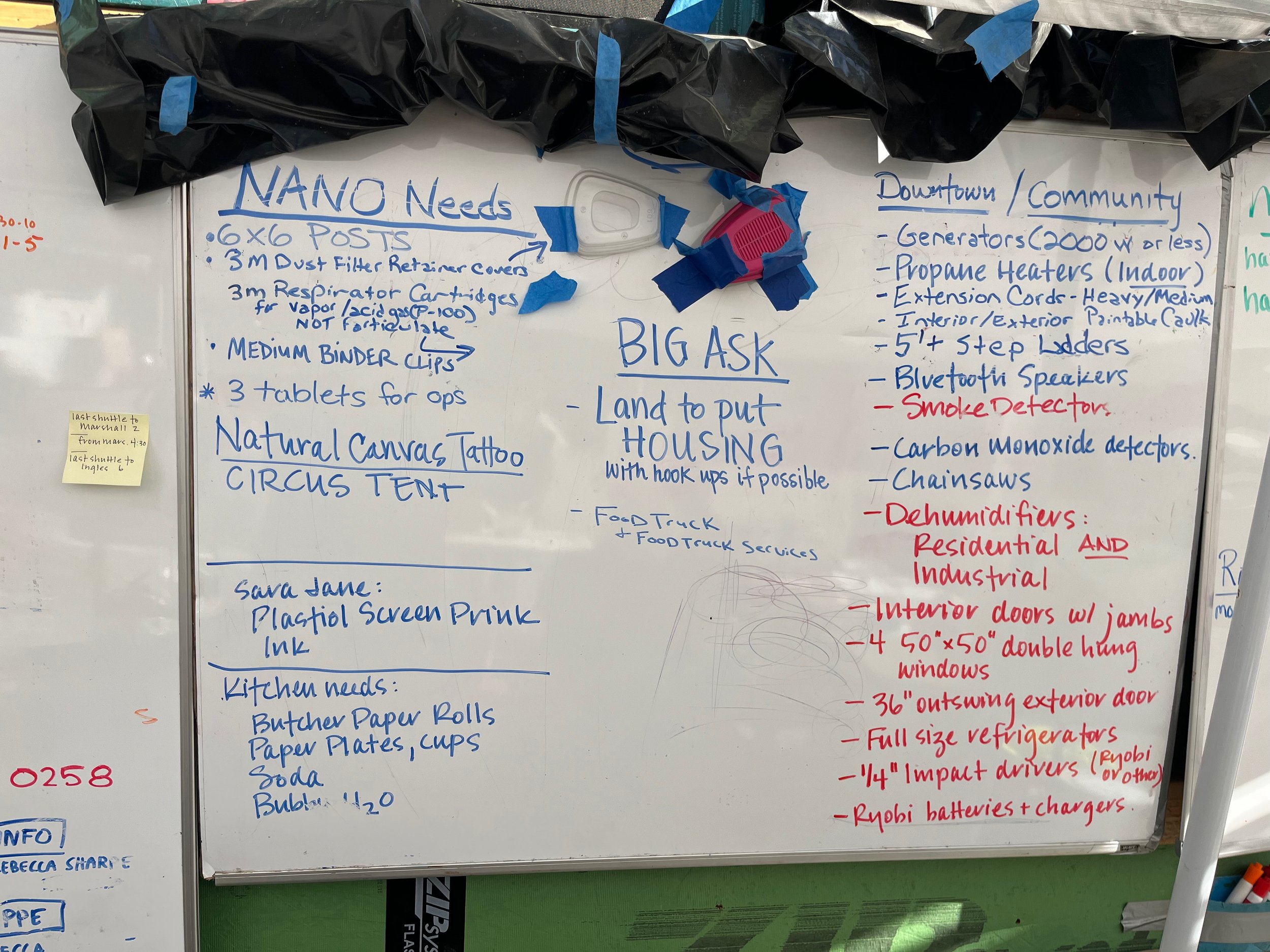

Justine Paradis: Mutual aid hinges on identifying what people need and getting that to them. It might sound simple enough, but to do that, ya gotta be so organized. At Nanostead, someone scrounged up a whiteboard, and hung it on the wall. This whiteboard is to this day the central place where people can literally write down a “need.”

MUSIC FADE

Becca Nicholson: We asked for things. We were like, ‘here's what we need.’ We learned we needed to be really, really specific about what we were asking for in terms of supplies and gear, and people came through for us, like the moment we'd run out of something, a whole truckload of it would show up here, and it was just kind of magic. And that just continued for weeks.

Justine Paradis: And that does that come from like putting stuff on like the Google Docs like needs list at Nanostead like that kind of thing?

Becca Nicholson: Oh, we didn't have a Google doc for a while. I think originally it was like word of mouth. People would come by here and take a picture with their phone of the, like, white board that we have, which is still happening. Um, a lot of us were posting on our own social media, just like, ‘hey, like Nanostead has this really important emergency need right now.’ Um.

[helicopter]

Justine Paradis: Is that a helicopter?

Becca Nicholson: Yeah, there's a helicopter. There's not as many of them as there used to be, but I guess I kind of tune them out now.

MUSIC: St. Augustine Red stems, Blue Dot Sessions

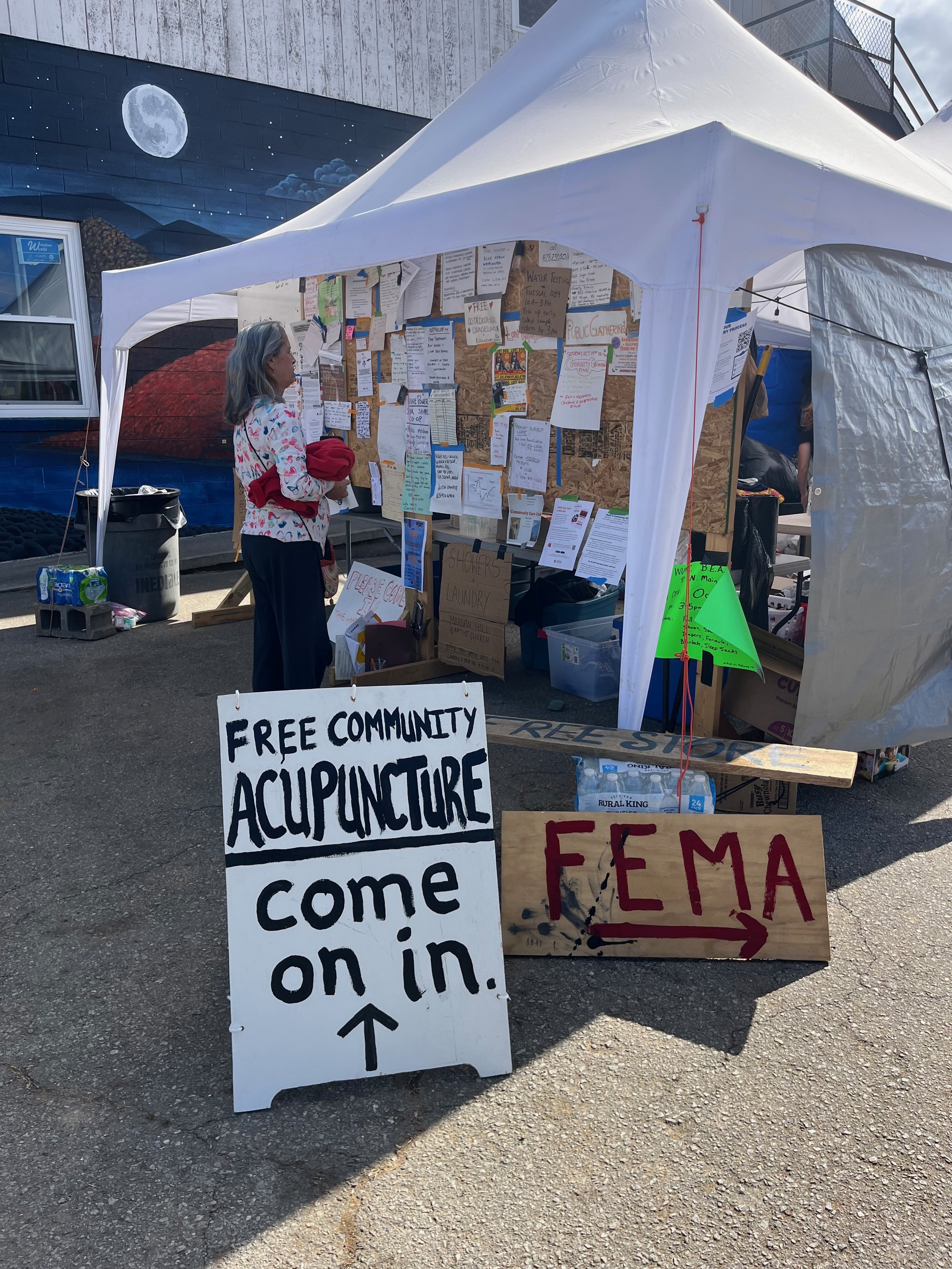

Justine Paradis: Nanostead Hub is of course far from the only mutual aid hub around. They are everywhere: in shopping plazas, churches, schools, old auto shops. Some are tiny and bare bones, like a community whiteboard someone hung up at the end of a driveway for their neighbors in their holler.

Others are big and official, sometimes run by the National Guard. Actually, the region was so overwhelmed with donations that organizing stuff just ended up being a huge job, and a lot of the soldiers found themselves spending their deployment sorting groceries.

These hubs are places you can get free stuff, like clothes or food or firewood. You can register at a FEMA tent or grab a hot meal from World Central Kitchen, the same organization that’s in places like Palestine. In some places, you can even have yourself an acupuncture session or get therapy.

Some hubs are supported by long term mutual aid groups who’ve been around for years and who know how to do this kinda work fast.

MUSIC FADE

Justine Paradis: But when it comes to Nanostead Hub, it didn’t exist before Helene. Somehow, it coalesced within days of the storm.

Josh Copus: I had a group of like professional disaster response people from California. I don't remember like who they were or what agency they were with, but like it was early days and they were like, ‘who's in charge?’ And I was like, ‘we are!’ …and they were just like, ‘we’ve actually never seen a civilian effort that is this tight.’

Justine Paradis: This is Josh Copus again.

Josh Copus: Receiving help actually takes a fair amount of administrative bandwidth. Like if just a bunch of people show up in this town without a plan and without someone to project manage them… and give them direction, like, they're in the way.

Justine Paradis: At this point, Nanostead is officially a charitable foundation, but at its heart, it’s self-organized and kinda anarchistic. Run entirely by locals. And people find their own place according to their strengths. Like Rachel Bennett.

Rachel Bennett: Also known as ‘Rachel Runner’… because I run between Nanostead and downtown.

Justine Paradis: Rachel had her hair in a long braid which she secured at the end by tying her hair back on itself, which I found very cool.

Rachel Bennett: I'm setting the fashion, you know?

Justine Paradis: It looks great. I love, I love how the reflective pants are around the fanny pack.

Rachel Bennett: Exactly. It's my marsupial pouch… It's funny because we have PPE fashion here. So, you know, we find what things that we like and, you know, we keep on adapting.

Justine Paradis: Rachel knew that she was not going to be able to dig out the mud, so she became an informal “personal relationship liaison,” as she put it. She marches a supply cart around downtown Marshall filled with snacks and PPE, and encourages people to swap out their dirty gloves.

Over by the shovels, I met Steve Matlack, wearing his nametag on his baseball cap and a t-shirt that said “laissez les bon temps rouler” – let the good times roll.

Steve Matlack: I showed up about a couple days after the storm, just to see if I could help out for a couple hours, and somehow I have never left. So I'm a full timer. More than full time here. I'm here every day.

Justine Paradis: Steve ended up finding himself responsible for the tool department.

Steve Matlack: Tarps, hoses, hammers, electrical bits, you name it. Box cutters. We have it… The number one thing that we send out by far are extension cords, electrical extension cords, the heavy gauge. Because of all the, uh, you know, generators we send out.

Justine Paradis: At their peak, Nanostead churned out 250 to 300 volunteers a day. That included a lot of locals, but also tons of people from all over the South and beyond. That Monday afternoon, they included a church group from Raleigh. For Keith Majeroni, it was his second trip to Marshall.

Justine Paradis: Why are you compelled to, you know, come and travel for the day with a group of people and come to this town that's not your own?

Keith Majeroni: Mainly, we're all out here to be the hands and feet of Jesus Christ. That's kind of what motivates us… um, we saw this whole community hurting out here. So… just to serve, serve the community, serve the Lord, and do what we can to help in the recovery.

Justine Paradis: Every day’s different. You never know who might show up. Like that Monday afternoon, Nanostead received a surprise delivery.

Justine Paradis: What's happening right now?

Becca Nicholson: Um, apparently there's a truck full of hamburger meat.

Anna Thompson: We get a myriad of donations here at Nanostead Hub in Marshall, North Carolina, and people have been so generous with answering our needs. Um, and this fine gentleman, I guess, is dropping off some hamburger meat for our auxiliary kitchen here which provides meals for all of our staff and volunteers. Delicious, delicious meals.

Becca Nicholson: Our staff? [laughs]

Anna Thompson: Shut up, it’s my turn.

Becca Nicholson: Are we staff?

Anna Thompson: No, we’re all volunteers.

Jim Purkerson: Yeah, we did, and we brought a whole trailer load from four churches, small country churches that we have. Everybody just poured their hearts out. We brought lots and lots of good items for these people up here that I know are in real need.

Justine Paradis: Yeah. That's beautiful. Yeah.

Reid Creswell: Lotta food. Lotta baby products, lotta clothes, bedclothes, pillows…

Justine Paradis: Well, safe drive back. Are you driving back tonight?

Jim Purkerson: Thank you.

Justine Paradis: Yeah. Amazing.

Kenneth Satterfield: Driving back tonight.

Jim Purkerson: We appreciate what you do too.

Justine Paradis: Appreciate you. Thank you.

MUSIC: Let There Be Rain, Silver Maple

Justine Paradis: There are plenty of stories or Hollywood depictions of people behaving selfishly, even violently in the aftermath of a natural disaster. But decades of sociological research tell a different story: that by and large, that’s not what happens. That overwhelmingly, in disaster after disaster, people behave generously. Share resources. Social barriers fall. Old arguments don’t matter. And neighbors help neighbors. Later, people often miss these times after a disaster. It’s not that violence never happens, it’s just that it’s the exception.

MUSIC BEAT

Justine Paradis: Still, disaster recovery is a long haul. During my time reporting, I ran into something a lot, pinned up on bulletin boards and or posted to Instagram. It was a line graph with peaks and valleys, titled “Emotional Phases of a Disaster.” Early on, there’s a honeymoon period when people are coming together. It’s a high.

Jazz Maltz: I don’t know where we are now.

Justine Paradis: Then, a precipitous fall as disillusionment sets in. A low that’s actually way lower than the disaster itself. A few people pointed at this cliff and said, “Look.”

Meredith Silver: I think we’re healing, I think we’re maybe at this curve.

Justine Paradis: The honeymoon period is over, and I’m about to hit disillusionment.

Josh Copus: The way that I survive and I think we all have is like, we need tiny victories, like, you cannot do this all at once. And it'll destroy you. The breadth of it is so massive.

Justine Paradis: And that’s the very reason Josh wants to host the ballad swap by the end of the month.

Josh Copus: This is my life. Like, I'm —yeah, hell yeah I'm gonna throw a little party. We need a little party!

MUSIC SWELL AND FADE

Justine Paradis: That’s after a break.

BREAK

[fun pick-up truck vibes]

Justine Paradis: It’s Tuesday morning, and I’m riding into downtown Marshall with my friends Alex and Melanie. It’s Alex’s pick-up truck. They’d both spent a lot of time in Marshall in the early days after the storm, digging out mud and powerwashing the street. But they hadn’t seen it in over a week.

Alex Barao: Oh right this is your first time down here.

Justine Paradis: Welcome to downtown Marshall. All twisted up.

Melanie Risch: Look at that. Look at all that junk in there. Oh my God. Car seats.

Justine Paradis: It’s a month after Helene. Melanie and Alex are pointing out how destroyed everything is, but also they’re seeing how much progress has been made. Like, you can actually see the street now. There are piles and piles of drywall torn out of buildings just lined up on the sidewalk. And one big change?

Melanie Risch: Look, the National Guard is doing traffic control.

Alex Barao: I know, I'm like, why can't I just go around? No. Good for them. [all laugh]

[door slam]

Justine Paradis: Hey.

Josh Copus: Hey!

Justine Paradis: How's it going?

Josh Copus: We're doing good.

We pull up to the Old Marshall Jail Hotel. Josh Copus and some friends have been working here all morning. They’re saving what they can, and dealing with a lot of trash.

Josh Copus: I'm just doing tractor.

Alex Barao: You're just doing tractor?

Josh Copus: Yeah, I'm doing tractor.

Alex Barao: Where?

Josh Copus: Out back! … Doing the things. We gotta set up for the ballad swap.

Josh Copus: You know, it's for the people, it’s for us, you know, it's for anyone that wants to come and listen to the songs and… feel that together. And so we’re doing it tomorrow.

Justine Paradis: It’s a big push. The entire first floor of Old Marshall Jail Hotel is still a construction zone. The drywall’s been torn out, and the framing’s left behind, wires and all. It’s also dirty. A lot of the mud has turned to dust, and when the wind kicks up, a few of us put on our masks.

Alex and Melanie jump in to help powerwash chairs for tomorrow night.

Later, one of the soldiers directing traffic asks Melanie out — while Melanie’s wearing a full-body tyvek suit and N95, demonstrably the hottest outfit there is these days.

Today, Josh wouldn’t be done here until 8 o’clock.

MUSIC: He Has a Way, Blue Dot Sessions

Justine Paradis: One odd thing about this disaster, and the climate crisis generally, is how wildly different it can be experienced in different places. Just fifteen minutes from Marshall, I spend an evening with Josh, Alex, and Melanie, in a beautiful house, listening to records and playing Magic: The Gathering. We sit around the dining room table while Alex cooks pasta puttanesca for dinner.

MUSIC FADE

Josh Copus: We're rebuilding our whole town. We're just doing it. And the contractors… they're basically working on 12 buildings right now. But they were like, it's, it's like one job. It's not 12 jobs like… it's the whole town… this is not a race. This is not a competition. Like, if I get my building open and the rest of the town is destroyed, like, what is the point of that?! I don't want to live in a destr– like we got to do it all together, so like we're building a strategy where like trade by trade, process by process, like you just cycle everyone through the —

Melanie Risch: It's drywall day!

Josh Copus: Drywall day!

Melanie Risch: And you just do the drywall in all the buildings.

Josh Copus: And you go, you go from one building to the next, and then the, you know, the… painters are there and like, you can do it, you can organize it in a way that actually creates a lot of efficiency. And people aren't like scrambling for resources… and not, I mean, that's just that's one part. There are other people. I mean, everyone's in a different space. There are people that won't come back.

Justine Paradis: Yeah.

Josh Copus: I think we're moving into that phase where, like, you start asking harder questions about rebuilding and what it costs and… I think it's going to get a little bit trickier now.

MUSIC: At the End of Nothing, Silver Maple

Justine Paradis: Let’s sit down and eat dinner now.

Josh Copus: Let’s sit down.

Justine Paradis: Thank you so much for cooking while we just chatted.

Josh Copus: That pork worked out, right?! [fade]

Justine Paradis: Something happened during Helene which might sound kinda basic – but after talking toa lot of people, I think its impact on the aftermath might have been actually huge. Because the cell signal went out for days, if you wanted to talk to someone, you had to physically go find them. This is very different from texting each other for updates, each in their own house. And I do think it helped set the tone of the recovery. Physically showing up – it says in a really profound way: we are here for each other, for real.

But now, like Josh said, the problems are getting trickier. And the needs that arise in the next phase, it might not be possible to write them on a whiteboard.

MUSIC SWELL AND FADE

Justine Paradis: One thing I haven’t said yet explicitly: the four days I spent in North Carolina, they were in the last week of October, literally days before the election.

[Nanostead ambi]

Justine Paradis: But there, people didn’t have a lot of headspace for the fever-pitch and division facing this country. They were very focused on what was right in front of them.

Keith Majeroni: Like how did this car, how did a car get up in a tree, you know? It's just, and, like, 40 foot shipping containers that were crushed like tin foil. You know, it's just you can't imagine the power of the water…

Justine Paradis: This is again Keith Majeroni. He’s at the decontamination station at Nanostead now, coming back from an afternoon of ripping out hardwood floors downtown.

Keith Majeroni: Yeah. I mean, I think in the aftermath of a disaster is where we really see the power of community… I've said to several people: learning that it's not the government that's going to fix the aftermath of something like this. It's the community. It's the Christians. It's the people in nearby towns and states that are going to come walk beside the people here.

Justine Paradis: It’s not that the national atmosphere or the federal government don’t affect what’s happening here at all. Dark conspiracies swirled after the storm, particularly focused on FEMA. Rumors that FEMA was confiscating relief supplies, or that all the aid was going to undocumented immigrants. Rumors that put barriers between aid and people who needed that aid most and that scapegoated communities of color. In at least a couple cases, these rumors also contributed to someone actually threatening FEMA workers.

But most of what I saw in the community that I moved through was the exact opposite of this kind of thing. What I saw was mutual aid everywhere and handwritten signs, reading “Thank you.” “Thank you for helping us.”

Ian Montgomery: I was getting really political before the storm. As soon as it hit, no. I wanted to be here with the people doing what they were doing, taking care of each other… Like I went home when I finally got internet back and I couldn't watch anything I used to watch… because it was disgusting.

Justine Paradis: Do you mind introducing yourself for the tape?

Ian Montgomery: My name is Ian Montgomery.

Justine Paradis: Ian Montgomery.

Ian Montgomery: Yeah. I've been doing inventory and equipment, receiving and distributing to people who need it, and it's been the most rewarding month of my life.

Justine Paradis: Why?

Ian Montgomery: Well, as I mentioned, I was getting, well, I didn't mention pessimism, but I was getting pretty pessimistic about the world and this renewed my faith in humanity and, you know, I'm not glad the storm happened. But I'm glad that what came out of it, and I've been a part of it.

MUSIC: Reverse (Instrumental stem), Silver Maple

Justine Paradis: In her book “A Paradise Built in Hell,” author and climate activist Rebecca Solnit wrote about the aftermath of disasters like Helene.

She argues that, in the mainstream, our culture is pretty individualistic. Meaning that, in everyday life, most of us are out for ourselves. We’re divided and lonely. In these ways, everyday life is a catastrophe in its own right. A catastrophe that a disaster like Helene can intensify, but far more often offers a reprieve. A time marked by togetherness, meaningful work, agency, and belonging to a greater whole.

“Disaster may offer us a glimpse but the challenge is to make something of it… to recognize and realize these desires and these possibilities in ordinary times. If there are ordinary times ahead.”

MUSIC POST AND FADE

[ballad swap crowd ambi]

Justine Paradis: Hiii!

Melanie Risch: I'm very well, um, I think Alex is there. Oh, and then you know these people…

Justine Paradis: The evening of October 30, Josh and Sheila Kay delivered on their promise of a ballad swap at the Old Marshall Jail. The promotion was entirely word of mouth. When I showed up, there was already a good crowd on the back patio.

Josh Copus: He-ey!

Melanie Risch: Hello!

Josh Copus: Hi!

Melanie Risch: How are you?

Josh Copus: Welcome to the ballad swap.

Melanie Risch: I know. It’s so great.

Josh Copus: This is a tiny victory…

Sheila Kay Adams: So we are going to sing some ballads for y'all. All y'all. Thank you for coming…

Justine Paradis: People found their seats in the freshly power washed chairs. The air felt warm and soft, and the patio twinkled with bistro lights, which miraculously still worked after the flood. The beer and wine had been pulled out of the mud and also power washed, and tonight, drinks were free.

Josh Copus: We made a commitment to have the ballad swap before the end of the month, and we're fuckin’ doing that.

[applause]

Justine Paradis: The custom at the ballad swap, Sheila Kay explained, is to start with the oldest person present. Tonight, that was Analo Phillips.

Analo Phillips: I’m going to sing this song in memory of all those that lost their life in this river. [singing] Oh, Death. Oh, Death. Won’t you spare over till another year? Well, what is this I can’t see? Ice cold hands taking hold of me. This is Death, none can excel. Holdin’ the key to heaven or hell.

Justine Paradis: When it was her turn, Sheila Kay sang a ballad about love ending in tragedy.

Sheila Kay Adams [singing]: Little Margret’s in her cold black coffin, with her face turned towards the wall.

Justine Paradis: Then, there was a surprise appearance.

Sheila Kay Adams: Is Rising Appalachia here?

Justine Paradis: Rising Appalachia had showed up, a beloved local folk band.

Rising Appalachia [singing]: Go tell my companions and children most dear to weep not for me now I’m gone. The same hand that led me through scenes most severe has kindly assisted me home.

Justine Paradis: The next singer, William Ritter, stepped up to the mic carrying his young daughter on his shoulders.

William Ritter: Pulling my hair. That’s alright. [singing] Father, now our meeting’s over, and we must part. And if I never see you anymore, I'll love you in my heart. We will land on the shore. We will land on the shore. We will land on the shore. And be safe forevermore…

Justine Paradis: Ballads are traditionally performed solo, but tonight, people started to join in. During the song, I looked at Josh, who was sitting behind me, and he was holding his face in his hands, quietly crying. The good kind of crying, I think. Tears for this tiny victory.

William Ritter [singing]: Friends, now our meeting is over, and we must part. And if I never see you anymore, I'll love you in my heart. We will land on the shore. We will land on the shore. We will land on the shore and be safe forevermore.

MUSIC: Let There Be Rain, Silver Maple

Justine Paradis: Thank you to everyone who spoke with me for this story. I cannot name everyone because it is a long list, but I’ll do my best.

The voices you heard we didn’t identify were Meredith Silver, Anna Thompson, Melanie Risch, Reid Creswell, Jim Purkerson, Kenneth Satterfield, Alex Barao, and Jazz Maltz.

Thanks to the folks at Nanostead, especially Kevin Ward and Jeremy Stauffer. Thank you to Rural Organizing and Resilience, aka ROAR and the folks at Poder Emma and Collaborativa La Milpa.

Thank you also to Aaron Stone, Clay White, and Luke Mitchell.

And a special thanks to Mil Norman-Risch, Alex Barao, and Melanie Risch for putting me up in Marshall and Burnsville.

By the way, the ballad swap is not the only celebration around Marshall. Last weekend, folks threw a volunteer appreciation party at Nanostead, including a PPE fashion show –

DJ: I’m hot, she’s hot, they hot, we hot…

Justine Paradis: We will post a video on our instagram, plus lots of pictures from my time in North Carolina. Follow us there. We’re @outsideinradio.

This episode was reported and mixed by me, Justine Paradis. It was edited by our executive producer, Taylor Quimby. The host of Outside/In is Nate Hegyi. Our team also includes Felix Poon, Marina Henke, and Kate Dario. Our director of on-demand audio is Rebecca Lavoie.

Music in this episode came from Cody High, Guustavv, Doctor Turtle, Blue Dot Sessions, and Silver Maple. Outside/In is a production of NHPR.

MUSIC SWELL AND FADE