Taxonomy's 200-Year Mistake

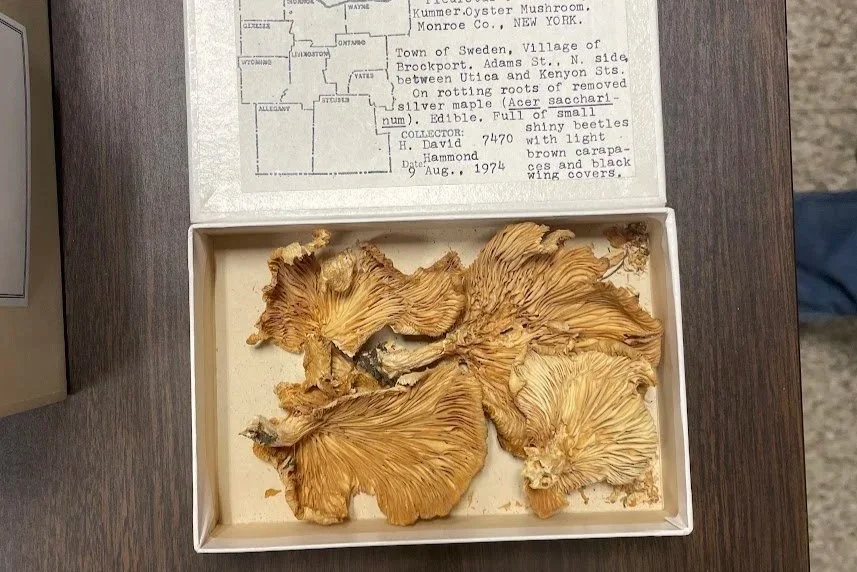

Patty Kaishian, the curator of mycology at the New York State Museum, examines one of the collection’s many polypores. The cocoa powder-like dusting on the fungi’s cap are its spores. Photo by Marina Henke.

Fungi used to be considered plants. Bad plants. Carl Linnaeus even referred to them as “the poorest peasants” of the vegetable class. This reputation stuck, and fungi were considered a nuisance in the Western world well into the 20th century.

Patricia Ononiwu Kaishian is trying to rewrite that narrative. Her new book, Forest Euphoria: The Abounding Queerness of Nature catalogs fungi that sprout from the shells of beetles, morph with their sexual partners into one being, and exhibit as many as 23,000 mating types.

Patty believes that fungi’s ability to defy our cut and dry assumptions about the natural world is actually their superpower. All it takes is to first accept that they’re queer as heck.

Featuring Patricia Ononiwu Kaishian.

ADDITIONAL MATERIALS

You can find Patty’s new book Forest Euphoria at your local bookstore or online.

Local to Albany? Visit the fungi exhibit that Marina toured at the New York State Museum: Outcasts: Mary Banning’s World of Mushrooms.

Patty has had the chance to name several new species of fungi. In 2021 she published an article documenting those species, with some pretty great photos of laboulbeniales (those are the fungi that grow from arthropod shells).

Check out C. L. Porter’s 1969 address to the Indiana Academy of Sciences where he critiques fellow mycologists for being “meek.” It’s brutal.

One of Patty’s favorite films is Microcosmos, a 1996 French documentary that investigates the daily interactions of insects. It’s not direct mushroom content per se, but it is beautiful.

SUPPORT

To share your questions and feedback with Outside/In, call the show’s hotline and leave us a voicemail. The number is 1-844-GO-OTTER. No question is too serious or too silly.

Outside/In is made possible with listener support. Click here to become a sustaining member of Outside/In.

Follow Outside/In on Instagram or join our private discussion group on Facebook.

CREDITS

Host: Nate Hegyi

Reported, produced and mixed by Marina Henke

Editing by Taylor Quimby

Our staff includes Justine Paradis, Felix Poon and Jessica Hunt

Executive producer: Taylor Quimby

Rebecca Lavoie is NHPR’s Director of On-Demand Audio

Music by Blue Dot Sessions, Jon Björk, Ludvig Moulin, bomull, Erik Fernholm.

Outside/In is a production of New Hampshire Public Radio

Audio Transcript

Note: Episodes of Outside/In are made as pieces of audio, and some context and nuance may be lost on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors.

Nate Hegyi: Hey, this is Outside/In, a show where curiosity and the natural world collide. I'm Nate Hegyi. A few months ago, one of our producers, Marina Henke, found herself on a field trip to the New York State Museum in Albany.

Marina Henke: Testing, testing. One. Two. One two. Testing, testing…

Nate Hegyi: It’s a building of sharp edges and gray concrete. Gives very strong Jetson’s vibes. But… what Marina was there to see is about as far from concrete as you’re gonna get.

Marina Henke: I mean I feel like the best way to describe it is like… a cabinet of curiosities of mushrooms right here. I mean, these are the most mushrooms I've maybe seen in my life right now!

[MUX IN, Into the Wild Woods, Epidemic]

Nate Hegyi: Mushrooms.

Patty Kaishian: …this is called fistulina hepatica, which the common name is the beefsteak mushroom. It gets that name because when you see it in the forest, it really does look like this piece of meat. And when you slice it, it even, like, exudes like a reddish liquid.

Marina Henke: No!

Patty Kaishian: … and it's edible and it tastes incredible...

Marina Henke: And so you can eat it?

Patty Kaishian: You can eat it… (FADES UNDER)

Nate Hegyi: This is Patty Kaishian, New York State Museum’s curator of mycology – that’s the study of fungi. She and Marina were standing in front of a big glass cabinet full of wax sculptures… like a Madame Tussaud’s, but for mushrooms.

Marina Henke: I mean, can you describe… like what is the texture of that cap?

Patty Kaishian: Yeah, so we would… in mycological terms we would say that's like “cerebriform.”

Marina Henke: What does THAT mean?

Patty Kaishian: Like brain shaped… so it has these pockets and grooves…

[Mushroom chatter fades out, MUX beat and fades]

Nate Hegyi: Watch HBO, open an Etsy browser, I mean heck try to buy some bougie coffee alternative… and it’s clear: mushrooms are having a moment.

Mushroom Influencer: Today is a first… mushroom foraging on the islands of Washington State…

Mushroom Documentary Narrator: There is a world under the earth full of magic and mystery…

Last of Us: Viruses can make us ill but fungi can alter our very minds.

Nate Hegyi: There’s a hit TV show about an apocalyptic fungus, a wave of new mushroom influencers. I’m told there’s even a bit of a mushroom fashion aesthetic.

Mushroom Crafters: Today we’re making wirette mushrooms… today we’re making a mushroom jewelry holder and trinket dish…

Nate Hegyi: But mushrooms haven’t always been so celebrated. In fact for most of the past century, they were seen by both scientists and non-scientists as kinda weird. And even bad.

Patty Kaishian: If you see them as first and foremost a group of beings that need to be eradicated then that's what you're going to expect out of them.

[MUX BACK IN]

Nate Hegyi: So today on Outside/In – how a whole generation of scientists came to detest mushrooms… And why Patty Kaishian is on a mission to correct the record.

Patty Kaishian: We are actually part fungus. We are part bacteria

Nate Hegyi: Stay with us.

[MUX ENDS]

AD BREAK

Marina Henke: This is Outside/In, a show where curiosity and the natural world collide. I’m Marina Henke. In most museums, there’s what the visitors see and what the curators see. Step into the back room of collections like the New York State Museum’s – and it feels like you’ve walked through some kind of portal.

Marina Henke: Yeah it says… let's see: anthropology, biology, geology, paleontology.

Patty Kaishian: Yes. And then within that there’s lots of subdivisions… (FADES)

Marina Henke: These days Patty Kaishian – again, that’s the director of the museum’s mycology collection – spends most of her working hours in a small office off this long hallway. Inside her lab are some microscopes, posters of fungi, and an old quote from a 19th century mycologist that says… “Oh what an outpouring of beautiful forms.”

Patty Kaishian: I try to mix it up what I have on that board, but it's hard to erase. So I leave it up for a long time (laughs)!

Marina Henke: Patty’s enthusiasm for fungi is palpable. Computer screen saver? Fungi. T-shirt print? Fungi. (By the way, both are right, but Patty says fun-JYE, not fun-GUY so that’s what we’re sticking with.)

Marina Henke: Anyway this fungi enthusiasm of Patty’s didn’t come out of today’s mushroom craze. It started in the woods.

[MUX IN, Potted Plant, Blue Dot]

Patty Kaishian: I spent a tremendous amount of time roving around the swamps and forests in the Hudson Valley.

Marina Henke: A self described “fugitive of suburbia” in Upstate New York, Patty was always one for the underdog species.

Patty Kaishian: I loved organisms that other people found to be creepy or weird, and I spent a lot of time in the company of, like, snakes and frogs and swamp creatures and stuff.

Marina Henke: Patty means this quite literally. In her parents front yard was a 4-foot wide culvert – that’s a human-made tunnel that lets water through. No headlamp. No bug nets. Just Patty, in a foot of water.

Patty Kaishian: So I would often just be like sort of lurking in there. I liked how dark it was. I liked the other creatures in there.

[MUX BEAT, FADE OUT]

Marina Henke: Her interest in fungi didn’t come until later in college, after a week-long summer class happened to spend one day on mushrooms. After that, there was no turning back. Patty’s now a formally trained fungi scientist at the New York State Museum - which houses one of the largest and oldest mycological collections in the country. She oversees a collection of more than 90,000 specimens.

Patty Kaishian: And then specifically, I've spent a lot of time doing taxonomic work.

Marina Henke: Taxonomic work. Patty tells me it’s seen as a bit unfashionable now, something straight out of the Victorian era, but… simply classifying organisms is the backbone to her job.

Patty Kaishian: So you're really interested in the individual species of that group and understanding their limits. Maybe you are actually writing descriptions for new species, naming new species and or you're doing studies about their evolution and their systematics. So how they relate to each other in the tree of life.

Marina Henke: Taxonomy found its beginnings in the 18th century with a man named Carl Linnaeus.

Patty Kaishian: So he was a Swedish botanist before Darwin… and gave us the system of binomial nomenclature, the two name system.

Marina Henke: Canis lupus. Homo sapiens. Linnaeus hoped that these neat & tidy names might bring order to a rather messy natural world. And, even though many elements have changed, that main structure Linnaeus sketched out… it stuck.

FANTASTIC MR. FOX CLIP: Cascade of Latin names (FADES)

Marina Henke: But a system of naming that finds its roots in the 1700s is bound to have some baggage.

Patty Kaishian: A lot of scientists at the time were explicitly religious or at least open to religious concepts.

Marina Henke: Before Linnaeus, before genus and species, there was something called The Great Chain of Being.

Patty Kaishian: So there are organisms that are at the top of this chain, and then they're organisms at the bottom. At the tippy top is – are people, the closest to God. And then anything descending on that chain is further from God.

Marina Henke: So here’s the order: It goes God, angels, humans, animals, plants, and finally rocks – or, if you’re being cute… minerals.

Patty Kaishian: The obvious implication of that is that the things at the bottom are not good. They're not good, they're not advanced… Whatever they're doing, they're doing it poorly.

Marina Henke: Medieval drawings of the Great Chain of Being are a lot to take in. At the bottom of the chain are fiery drawings of hell: humans in pots of boiling water, something that looks a lot like a live-dissection. Let’s just say, they’re far from the clinical drawings of phylum and class that filled my elementary school textbooks. But… even though Linnaeus’ system sought to be non-religious, he would have been well versed in the Great Chain. And the similarities show it. Linnaeus’ three major kingdoms come straight from its ranks: animal, plant and mineral. With the stroke of a pen, or perhaps a quill, Carl Linnaeus was setting a framework for categorizing the natural world. But when it came mushrooms, there was a problem.

[MUX IN, Hidden in Havana, Epidemic]

Patty Kaishian: He really did not like fungi

Marina Henke: For one thing, fungi were just hard to classify.

Patty Kaishian: And he definitely didn’t seem particularly interested in understanding them… there was even like I think a palpable disdain for them.

Marina Henke: And so Carl Linnaeus is looking at a mushroom and he's being like, that's gross.

Patty Kaishian: That's gross. Yeah I don't like that. Laughs.

Marina Henke: So in 1753, Carl Linnaeus classified fungi as a plant. A bad plant. They had no roots, no stems, no leaves. Instead… here is an organism that loves a dark and wet place, can kill you if you eat the wrong one, and comes in textures similar to a brain, wet meat, and slimy fish. Some smell like rotting flesh. Others can essentially sprout a genderless penis overnight (this by the way is technically what a mushroom is… the reproductive arm of many fungal bodies). Linnaeus put them at the very bottom of the plant kingdom, right above rocks. In one now infamous essay …

Patty Kaishian: ...he referred to lichens, which are part fungi with a photo- synthetic partner… he called those things rustici pauperimi...

The “poor peasants” of the vegetable class.

[MUX PEAK AND OUT]

Marina Henke: But, all those years ago, Linnaeus made a mistake. Fungi aren’t plants.

Patty Kaishian: They're actually more closely related to animals than they are to plants, like evolutionarily.

Marina Henke: To be a fungi you need to share a couple common characteristics:

Patty Kaishian: You know, they typically bear spores…

Marina Henke:… those are fungi’s way of reproducing –

Patty Kaishian: A lot of them have chitin somewhere in their cell wall.

Marina Henke: … insects have that too… it’s what makes lobster or beetle shells hard…

Patty Kaishian: it's also in like other animals, but it's not in plants.

Marina Henke: And finally… unlike plants, which use photosynthesis to turn sunlight into energy… fungi have to EAT. This is called being heterotrophic, and is one of the biggest things to set them apart from plants. But despite ALL THESE differences, fungi wouldn’t get their own kingdom until 1969! That’s the year humans first landed on the moon.

Patty Kaishian: It was hundreds of years that they languished as incorrectly classified….

Marina Henke: Patty by the way doesn’t totally fault Linnaeus for this classification mistake. Taxonomy is hard business, and what Linnaeus saw was an immobile organism with rigid cell walls… sounded a lot like a plant to him. But…

Patty Kaishian: It was also the lack of curiosity about them.

[MUX IN, First Results, BlueDot]

Patty Kaishian: And so a lot of mycologists we like kind of think of his work as pretty much, you know, setting the field of mycology back significantly from a biological perspective

Marina Henke:Let’s just say, having the grandfather of taxonomy find you gross didn’t set up fungi for reputational success. Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth century, mycologists struggled to be taken seriously. Few universities developed mycological study programs. And those that did, had a hard time finding funding and recognition. Mycologists were often pigeon-holed as light-hearted forest-loving foragers… one essay I found from the 1950s compared meetings of the Mycological Society to a reunion of nostalgic war veterans, happy to “swap collection experiences and quibble over moot points of taxonomy and nomenclature.” That attitude hasn’t gone away.

Patty Kaishian: Even now with the growing interest in mycology, you’re still like not taken that seriously by a lot of people, right. Like, oh, you study mushrooms, you know, like it's like it's like kind of a thing.

Marina Henke: Basically… become a professional mycologist and people think you’re either obsessed with psychedelics or… trying to poison someone.

[BEAT]

Marina Henke: But… mycologists are a persistent (if not obsessive) bunch. And turns out, if allowed to occupy a kingdom of their own… You’ll discover that fungi are amazing. Even that sentence I said just a few minutes ago…

Marina Henke [SLIGHT ECHOE-Y REVERB]: “Here is an organism that loves a dark and wet place, can kill ya if you eat the wrong one, and comes in textures similar to: a brain, wet meat, and slimy fish…”

Marina Henke: What if I said this instead? Here is an organism that’s underground root system supports nearly all living plants. With a species that can be SO individualized as to only grow on the particular side of the LEG of a BEETLE. And an organism that we have barely begun to understand. Scientists believe they’ve only catalogued less than 10% of fungi species.

[MUX PULSE AND FADE]

Marina Henke: Our human tendency to categorize – it brings good and bad. We find empowerment in being part of a group, waving a flag, finding support with those who understand. And also… to categorize has meant to disempower. To discriminate, to ostracize. Taxonomy also holds both sides of the same coin. Carl Linnaeus’s book that names fungi as a plant – A General System of Nature – influenced the early eugenics movement. And, categorizing humans on their own “chain of being” paved the way for centuries of scientific racism. The question for me then, was how does Patty – a person who deeply believes in science – hold all these truths at once?

Marina Henke: This is a system that kind of did fungi dirty for a while. You know, like it didn't let them be all that they wanted to be. How do you think of that as someone who now like, your work is like it is embracing the taxonomy system?

Patty Kaishian: Totally. When you think about science, it's a very powerful way of knowing. It's a tool, it's a methodology, and it's not a dogma.

[MUX IN, Nyar, Epidemic]

Patty Kaishian: I am interested in, like going through the scientific canon and history within mycology and asking these types of questions like, well, why is it that we assumed that most fungi were dangerous and deadly and gross? Or what taxonomic failures exist in terms of understanding these really dynamic creatures? And then sort of using the things I like about science to, like, reexamine those things.

Marina Henke: Much of this reexamination is happening right here, in this lab. Coming up, Patty looks at fungi through an expansive lens: the radical new framework of "queer ecology." That’s after a quick break.

MIDROLL

Marina Henke: This is Outside/In, I’m Marina Henke.

Marina Henke: Oh, wow. This is so cool!

Marina Henke: I’m back with Patty Kaishian, the curator of mycology at the New York State Museum.

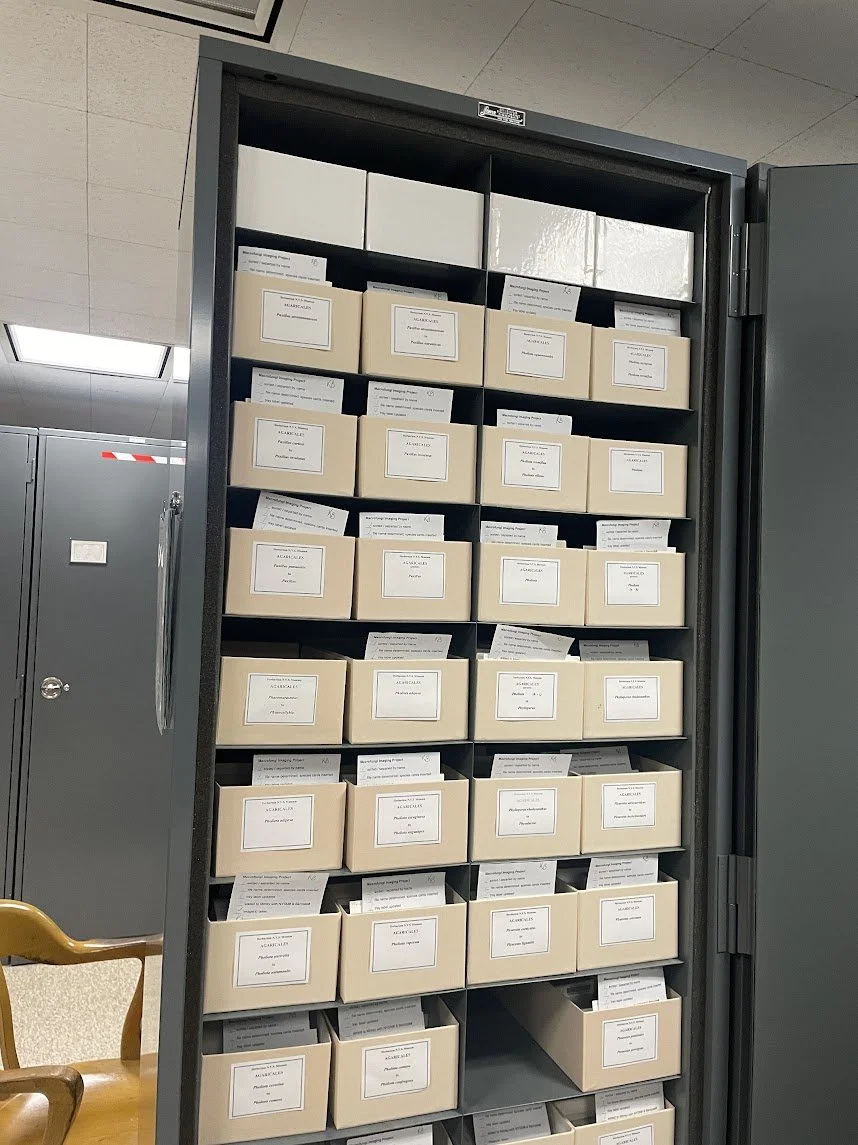

Patty Kaishian: So right now we're looking at a cabinet that has tons of little boxes that are basically like shoeboxes full of smaller boxes that have the fungi in them.

Marina Henke: Yeah. I mean, let's see plurotis...

Patty Kaishian: Pluroteosteosis.

Marina Henke: The box in front of us is marked with a scrawling cursive. It’s part of the museum’s mycological collection, which Patty is showing me right now. In front of us are rows and rows of boxes within boxes - samples of mushroom caps gathered from all across the state.

Patty Kaishian: So this was from 1964, Chenango County in New York. (GASP… wow!) And so this is, this is like a pretty iconic, um polypor. The brown dust on top is actually spores.

Marina Henke: Can I touch it?

Patty Kaishian: Yeah, you can.

Marina Henke: I mean yeah so the top, those spores it looks, I’d best describe as cocoa powder.

Patty Kaishian: Yeah that’s exactly what it looks like to me.

[MUX IN, Palms Down, Blue Dot]

Marina Henke: We live in a beautiful and diverse world. But embracing the utter strangeness of fungi invites a degree of open-mindedness. Patty approaches her work from a lens of what she calls queer ecology. It’s the subject of a book she recently published – Forest Euphoria: The Abounding Queerness of Nature.

Patty Kaishian: I would say queer ecology is an approach to understanding how nature and biodiversity may be, um, existing outside of heteronormativity

Marina Henke: Now this is not yet an official scientific term, like “benthic ecology” or “forest ecology,” and not every scholar will approach this framework identically. Patty breaks it down into two ways. This first element of queer ecology is a lot about… well… sex.

Patty Kaishian: So it's sometimes, you know, talking about non-binary sexes in nature or strategies of reproduction that are not consistent with a binary conception of sex. It can also be about understanding, you know, how organisms might transition like sexually in their lifetimes

Marina Henke: When it comes to sex, two assumptions have long dominated the natural sciences: that each organism has one and one sex only, and that only males and females reproduce. A queer ecology framework disagrees with this assumption that sex and reproduction are so straight forward.

Patty Kaishian: We look at like reproduction and sex as this sort of plastic fluid thing that can exist in many, many different forms.

Marina Henke: But queer ecology is more than just who’s having sex with who. If science is a discipline that depends on rule making, a queer approach asks questions of who makes the rules.

Patty Kaishian: Queerness is also a term that’s used in this more abstract sense. So when you talk about queer theory you're trying to understand kind of what is considered normal and what is considered deviant . And how did those classifications come to exist?

Marina Henke: You may already see where this is going, but may I present perhaps the case study for queer ecology: Fungi.

[SHORT MUX BEAT AND FADE OUT]

Marina Henke: Up first: the reproduction of it all.

Marina Henke: Can we go into, like the nitty gritty of the, the, the sexual diversity side of it? I mean, you said a couple minutes ago that some fungi can have thousands of types of mating types. What is going on there?

Patty Kaishian: So sometimes you can visually look at a fungus and say that’s the male or that’s the female one, that’s true with some flowers too and other… you know obviously animals is something we’re used to doing that with. But then there’s also fungi that you can’t visually detect their sex and it would be on the genetic level.

Patty Kaishian: The fungus that gets brought up a lot, I like to say, it's a queer icon. It's schizophyllum commune.

Marina Henke: Sounds like a queer icon!

Patty Kaishian: Yes! Or the common split gil, that’s the common name. That fungus has, it’s kind of famously the one with, uh, you know, tens of thousands of mating types.

Marina Henke: Again, this isn’t something that the human eye can see.

Patty Kaishian: In their genome there are like particular genes that code for their capacity for sexual reproduction and there are a lot of different types of genetic combinations that can be made through this recombination process.

Marina Henke: Some fungi have male and female reproductive structures in a singular body, whole species are asexual – and reproduce all on their own. Occasionally two fungi’s mycelium – that’s sorta like the roots of a fungus – will meet underground…

Patty Kaishian: You know, they might recombine their genetic information and then retreat from one another, or they might fuse and then sort of stay together indefinitely as like a kind of singular body with multiple individuals in one.

Marina Henke: Two individuals essentially become one. For a long time scientists chose to downplay or ignore the obvious sexual diversity of fungi – and other organisms – and it showed. This includes Sigmund Freud, who, before he became a famous psychoanalyst, was an accomplished biologist. When studies on eels began to show that the creatures only developed testicles late in life… Freud went so far as to remove those investigations from his list of publications. Researchers who published accounts of swans showing same-sex nesting habits were told by colleagues they must had misunderstood results. That discomfort – to disrupt the binary – has left considerable gaps in scientific literature.

[MUX IN, Shelftop Speech, BlueDot]

Marina Henke: Let’s return to fungi here. A field where mycologists feel as though they’re years, decades even behind – because of this impulse to ignore quite blatant sexual queerness.

Patty Kaishian: I think mycology is like a really dynamic example or like – a case study – in queer ecology, because we have both this queer reproductive thing going on throughout so much of the kingdom. And then also we have this history of organisms that were considered bad, considered gross and disgusting, and also like a threat to like established order. You know, fungi as disrupting of agriculture, fungi that were medicinal in a way that created visions and, you know, might be used in witchcraft.

Marina Henke: That threatening feeling has infiltrated the structural institutions of science – at many universities mycologists work within “Forest Pathology” programs – pathology is the study of diseases. These decisions were made at a time when fungi were studied as the problem child of the natural world (hello Irish Potato Famine). And they’re decisions that are hard to reverse. When Patty got her masters degree… she did it under the Forest Pathology and Mycology department.

Patty Kaishian: If you see them as first and foremost a group of beings that need to be eradicated, eliminated, quelled then that's sort of what you're going to expect out of them.

Marina Henke: Patty calls this a classic “confirmation bias.” What’s killing our trees? Fungi. What’s killing our crops? Fungi.

Patty Kaishian: But that’s just one element of SOME of their biologies right? Many others are doing things that are enabling the forests to exist and enabling these really dynamic mutualistic partnerships.

Marina Henke: Fungi’s queerness makes for some easy comparisons to human life – a species filled to the brim with queer people living queer lives. But this ecological framework, which asks questions of how these things are studied and treated and… sometimes vilified… draws similarities out in a pretty powerful way.

CLIP MONTAGE OF TRANSPHOBIC POLITICAL SPEECH: (Donald Trump) It will henceforth be the official policy of the US government that there are only two genders: male and female….(News Anchor) This case was brought by some parents who objected to the presence of books with LGBT characters without a chance to opt out for it…

Marina Henke: At the same time though – we do not have rust colored spores. Or the ability to decompose things which have died.

Marina Henke: You write a lot about how you, you see this in fungi and it makes you see sort of a mirror to you. Right? It is, it is not an othering experience, it is an oh my gosh, this this feels like a world of queer potential. I feel like there's a different way someone could hear like, this thing has 23,000 mating types, and it's doing this thing where it becomes a they with like these roots. You could be like, wow, that sounds so far from human. How would you, as someone who feels the opposite like respond to that?

Patty Kaishian: So I think, like, for me, one of the things that I really want people to understand is that like difference and diversity is really important. It's really important in nature. Right. I write in my book, it's the very premise of nature, right, that there are different forms of beings that have these arrangements and ways of coexisting and sharing space and sharing energy as it moves through, like ecological webs…

Patty Kaishian: It's not a universally human trait, I don't think, but I think American culture in particular is very reactive towards difference and seeks often to suppress it. Right, to, to quash any, any sort of emergently different thing.

[MUX IN, King Billy, Blue Dot]

Patty Kaishian: I think it's a really important thing to, like, just go through this practice of sitting with the discomfort of what – why are you feeling uncomfortable when you see something so different? Where does the desire to crush that difference come from. Is that something you actually believe in? Do you actually want to replicate that or are you just kind of going through the motions that you've absorbed through the society at large? Right. Like when a little creature comes through your house and your instinct is to to kill it, why? Are you actually… do you actually want to kill it or is it an instinct?

Marina Henke: My act of writing this very episode was an exact exercise in pushing against that discomfort. I am one of those people who doesn’t love to linger on a newly sprouted mushroom. Maybe you are too. And I can level with myself – there’s a reason to be scared of snakes, of spiders, of mushrooms – these things can and do kill you. I wonder how much there’s some ancient evolutionary wiring in all of us to just feel that echkkk. But Patty asks us to question whether when we feel that discomfort there’s something more going on.

Patty Kaishian: Part of what I want for people to do is not to be like, okay, you are a fungus like you are, you know, like, you know. Yes. Okay. There are key differences, but the differences are not bad..

MUX PULSE

Patty Kaishian: We are actually really weird, like people, animals, we're, we're these species that are just infinitely strange, right? Like, in terms of, like, the fact that we exist at all, that we evolved at all that we have within our bodies like more fungal and bacterial cells than we have human cells.

Marina Henke: It’s true. Around 38 trillion to be exact.

Patty Kaishian: Mushrooms are amazing teachers… And one of the things that they teach us is, you know, a sense of, like, interdependence that we arenot easily definable, that we are part of a larger network … PAUSE… I would hope that people have that takeaway.

END

[CREDITS MUX, Jackknife, Epidemic]

Nate Hegyi: This story was reported produced and mixed by Marina Henke. It was edited by our executive producer Taylor Quimby. I'm your host, Nate Hegyi.

Marina Henke: Check out our website where you can find photos of my trip to New York State Museum’s mycology collection and information about Patty’s book, Forest Euphoria. It’s available wherever you get your books. You can also see some photos of labouls, those are the fungi that grow from the shells of beetles and my gosh are they wild.

Nate Hegyi: Our staff also includes Justine Paradise, Felix Poon and Jessica Hunt. Rebecca Lavoie is NPR's director of on demand audio.

Marina Henke: Music is from Blue Dot Sessions, Jon Björk, Ludvig Moulin, bomull, Erik Fernholm.

Nate Hegyi: Outside/In is a production of New Hampshire Public Radio.