After the Flood

Times Beach was a town that was wiped off the map by an environmental disaster. But once the houses and streets were gone, the town was wiped away a second time, this time in a way that may make it difficult to learn from the mistakes of the past.

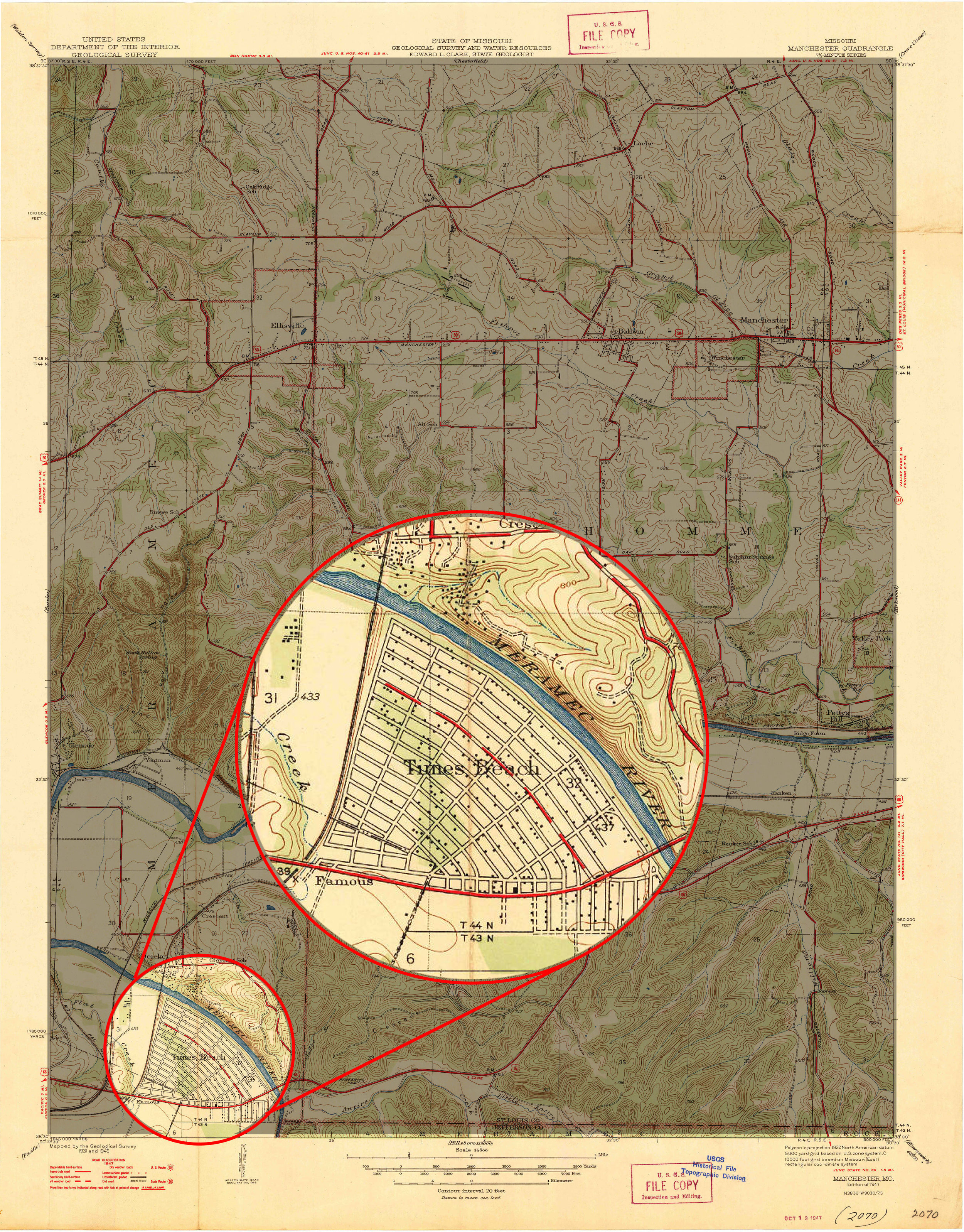

US Geological survey map from 1947 with Times Beach highlighted. | Source: USGS.gov

Marilyn Leistner knew the drill when it came to floods. In her hometown of Times Beach, Missouri—a small town that hugged the Meramec River outside St. Louis—flooding was a fact of life. Every time the waters rose, she and her family would put the furniture up on concrete blocks and tie up the drapes just in case, but the water almost never got into their home.

But the flood of 1982 was different.

“We barely got out with our lives,” Marilyn says. “We were at the last minute—with the floodwaters lapping at the front porch—putting things up in a safe place.”

With the water rising fast, Marilyn, her husband, one of their daughters, and the family’s dog all got on a boat to leave. The water was swift, and a pallet rushing by hit the motor. It knocked out the forward gears and they had to escape in reverse, but they motored to safety through the streets of the flooded town.

Times Beach was a close knit working-class neighborhood of about 2,000 people, many of whom worked at the Chrysler plant just down the highway. There was a baseball diamond where the hometown team, The Sons of the Beach, played. It was the kind of place where kids grew up to marry their high school sweethearts and stayed to start a family.

But when the floodwaters crested 24 feet above normal on December 6, 1982 all of that was underwater. It was a 500-year flood; homes were wrecked, heirlooms and photo albums ruined.

“I was really devastated,” Marilyn says. “Sometime through the flood event [the] back door on our home came open and a lot of stuff floated out. I have no pictures of my kids back then.”

She didn’t yet know it then but they would lose a lot more than just those old photos. Marilyn and her family would never live in their home again or in Times Beach for that matter. No one would. But not because of the flood.

The Men in White Suits

As the water receded after the 1982 floods, when people would typically be getting ready to clean up, rebuild, reclaim their homes, the people of Times Beach got some bad news. Times Beach was about to be the site of one of the biggest environmental cleanups in U.S. history.

The beginning of the end of Times Beach actually started 10 years before. In the summer of 1971 dozens of horses in the area started to die. Next, birds and cats started to drop dead, and a few months later, two little girls came down with a mysterious illness. At first it seemed like the flu, with headaches and diarrhea, but then one day the family had to rush one of their daughters to the hospital with terrible stomach pain: it turned out her bladder was inflamed and bleeding. Other people started getting nasty symptoms too: nausea, headaches, hair loss.

Federal health officials launched an investigation but ten years went by without much action. That is, until November 1982, just before the flood, when the men in white suits showed up in Times Beach.

Marilyn remembers it like something out of a science-fiction movie. “Kids were out there playing in regular clothes—shorts, no shoes—and here are these men in these moon suits taking soil samples,” she says. “It was scary.” Another longterm Times Beach resident, Cindy Reid, says the workers in hazmat suits on her street wouldn’t say why they were taking samples.

But the 2000 residents of Times Beach didn’t have time to worry about the men in the moon suits. They had a bigger problem on their hands: the river.

Just weeks after the EPA started testing the soil, heavy rain hit Times Beach, and didn’t stop for four days. Cindy, her son Michael, and her husband Nick, watched as the flood waters rose through the town. The water was warm, she remembers, as it rose around her ankles and then her knees and finally her chest. They decided to leave.

Cindy and her family walked four miles to a dry spot overlooking Times Beach. The town was wrecked. The streets where Michael and the other kids would have block-wide snowball fights and the field where the Sons of the Beach softball team played was sitting under swirling, muddy river water. The grocery store where Cindy would do the family’s shopping was gone. There was five feet of river water lapping at the walls of their living room.

Looking over the flooded town below, Cindy’s family tried to figure out what they would do next. They took a vote between them and decided to stay and rebuild. “You do what you have to do,” she says.

But they never got that chance. On December 23, 1982, federal and state authorities told everyone to evacuate Times Beach. If residents already left their homes, they were told not to come back.

That’s because the men in white suits had found something: there were dangerously high levels of something called dioxin on the streets of Times Beach. Dioxin is a toxic byproduct of a lot of chemicals but it’s best known as an ingredient in Agent Orange.

The U.S. military used a herbicide called Agent Orange during the Vietnam War. It’s been linked to skin burns, cancer, and liver failure in veterans. Mothers who were exposed to it had babies with terrible birth defects. Experts found levels of this stuff in Times Beach that were 100 times higher than what was considered safe.

So, how did dioxin end up in a small town in Missouri?

The Making of a Superfund Site

Well, like a lot of small towns with modest budgets, most of the roads in Times Beach were unpaved and dirt roads can get dusty. Back then, one cost-efficient way to control the dust was to spray motor oil on the roads.

And that’s where a waste-oil hauler named Russell Martin Bliss comes into the story. A chemical plant in southwest Missouri hired Russell to dispose of waste from the facility. Now, guess what this factory used to produce? Agent Orange. Russell has always claimed he didn’t know the sludge he had was dangerous and so he did what he had always done before: mixed the sludge with waste oil and started spraying. He sprayed it at stables, church parking lots, his own farm, and the dirt roads in Times Beach.

Cindy remembers the neighborhood kids used to ride their bikes behind the Russell’s truck as he sprayed the roads. “There wasn't a kid down there who didn't wear that oil,” she says.

In 1983—just a few months after the flood—and shortly after the guys in white suits discovered dangerously high levels of dioxin in its soil, Times Beach was named one of the first Superfund sites in the United States.

If you’re like most people, and only have a nebulous idea of what the Superfund law actually entails, here’s a quick history lesson. People back in the 1970s and 1980s were really freaked out by toxic waste—and rightly so. There were two cases in particular that made headlines. One of them is called Love Canal, which was a town in western New York outside of Niagara Falls where toxic waste had been buried for years. A local school was built on top of the waste dump, and the result was disastrous. There was also the so-called Valley of the Drums near Louisville, Kentucky. The name kind of says it all: thousands of barrels piled up in shallow pits leaking toxic waste into the groundwater.

US Geological survey map from 1985, with Times Beach highlighted. | Source: USGS.gov

So, in response to these and other cases, President Jimmy Carter signed the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 that set aside a “superfund” of more than $1.5 billion to clean up these places. The money is also used to buyout the people who were living in these dangerously polluted areas because—let’s face it—nobody is going to buy a house in a toxic waste dump. And that’s what the government did next: buyout the folks who lived in Times Beach.

In 1985 the last family left. By this time, Marilyn was mayor but she was a mayor with no town. The city disincorporated. Times Beach was officially a ghost town.

The Cleanup

When Gary Pendergrass, the project coordinator for the cleanup, arrived in Times Beach the first time he found an eerie sight.

“There were a lot of Christmas decorations outside in the yards,” he remembers. “A lot of the houses were like the people had just basically stood up and walked out and never came back.”

Now that everyone was out of the town, the cleanup could begin.

The EPA’s plan said that everything had to go. Bulldozers rolled through the streets of Times Beach knocking down homes and shops. All the debris—from the abandoned Christmas decorations to the town’s water tower—was gathered and piled in a mound that covered four football fields.

One afternoon, Marilyn points out the unassuming grass-covered hill that holds the remains of the town.

“In that mound are all the homes, everything that was precious to the people who lived here,” she says, driving past it and the empty land around it that once was the town.

The EPA buried the debris from Times Beach under a watertight barrier and capped it with a foot of clean soil. It took less than a year to tear down the 700 some odd buildings in the town. The technical name for that mound is a sarcophagus: a tomb for an entire town.

Anything that wasn’t buried was burned. And there was a lot to burn. The newly razed town of Times Beach became the home of a giant incinerator dedicated to burning the dioxin out of the contaminated soil from Times Beach and more than two dozen other sites sprayed by Russell Bliss.

“We’re not talking about a big bonfire,” says David Shorr, who was the director of the MIssouri Department of Natural Resources during the cleanup.

“We’re talking about dirt and there was a lot of dirt!” he laughs.

Any soil that had more than 10 parts per billion of dioxin was burned at temperatures as high as 2,000 F. Soil with less than 10 parts per billion of dioxin was buried under 12-inches of clean dirt. All told, more than 250,000 tons of soil was processed at Times Beach.

So, picture that scene: homes razed, streets are all torn up. All the material is feeding into either a giant tomb in the ground or the fiery maw of an incinerator. It sounds like some kind of hellscape, right?

But, during all this, something else was happening. Mother Nature was taking over.

“I remember sitting in Times Beach, a beautiful sunny day with one of my good friends and colleagues, John Young, who was responsible for the project,” remembers David, “and we were eating lunch and we’re both looking at each other going, be a hell of a park.”

That’s right. Times Beach—the Superfund site—was about to become a Missouri State Park.

From Superfund to State Park

Photo: Zach Dyer

It might seem crazy—turning a place that was once so polluted that an entire town had to be bulldozed into a park—but it happens all the time. According to the EPA, as of 2011 there were more than 100 cleaned up Superfund sites in use as recreational green space. That means parks, soccer pitches, baseball diamonds.

So if it’s safe enough for a park, why not just build homes on it again? Well, while the surface is safe there’s still this layer of moderately dioxin-laced soil just a foot below. Officials don’t want people digging around out there. The idea is for people to visit but not stay.

“People are not supposed to be living in state parks,” says David. “You can come every day and still not get the exposures that would be there for somebody who’s living there or an exposure that would put you at risk.”

The cleanup work was finished in 1997 after 12 years and more than $200 million. So, with the remediation complete, a decision had to be made: What to call this newly-minted state park?

David had his doubts about embracing the site’s history directly.

“A cleaned up waste site alone is not a theme for a state park, but it’s Route 66,” David says, referring to the historic U.S. highway that forms the southern border of the erstwhile town.

Route 66 State Park opened to the public in 1999.

Marilyn was happy to see the land safe and open to the public but she has some misgivings about the attempt to move past the stigma around the town of Times Beach.

“With the former residents it's like they feel like they have wiped out everything that they knew and loved here,” she says. “That's part of the reason why there are residents who won't come here anymore. There are residents that wouldn't come back here for any reason.”

Photo: Zach Dyer

Visitors to the park today won’t see any information or signs on the grounds that say the town of Times Beach was ever there. There’s nothing but a few groundwell monitors sticking out of the unmarked landfill.

There is a visitor center for the Route 66 State Park. Inside there is a small display about Times Beach with photos of what the town used to look like and there is a bit about the dioxin scare. A plaque commemorates it as “one of America's greatest triumphs over environmental disasters.”

But to get to that exhibit, visitors would need to walk into the back of the center, past a gift shop and nostalgic neon road signs for gasoline and restaurants. And that’s only if they knew to drive a couple miles down the highway from the actual park and, well, it’s just not much.

“I think everybody from the Beach kind of thought that visitor's center would have a lot more,” says Cindy Reid. “Times Beach was there and it was a place and it's not anything to be ashamed of that you're from there.”

“The dioxin part is a half inch,” she says. “The history part and the family part is two foot. So why should this half inch overrun everything that went before it?”

It’s easy to lose sight of the story of Times Beach in favor of the park that’s there today, but it doesn’t have to be this way. Just 30 minutes north there’s another park that was also once a Superfund site. It’s called Weldon Spring. It’s a former munitions factory that processed uranium ore as part of the Manhattan Project during World War II.

But at Weldon Spring, the site’s history is celebrated, not hidden. There’s a 10,000 square-foot museum. Tourists are encouraged to hike to the top of the concrete dome that caps off the radioactive waste. There’s even a nice view of the Missouri River.

The sarcophagus at Weldon Spring isn’t a tomb. It’s a plaque. And by comparison Times Beach feels like a coverup.

It’s not hard to understand why someone would want to highlight the role Weldon Spring played in developing the atomic bomb and sidestep around the story of dioxin and Times Beach. But the story of Times Beach—of the people who lost everything—has a lot to say when it comes to problems we’re still wrestling with today: things like, how do we responsibly get rid of toxic waste? Who’s keeping an eye on it? And what’s at stake if something goes terribly, terribly wrong like it did in Times Beach?

If we don’t know about it, aren’t we just destined to repeat it? Marilyn Leistner thinks so.

“There are times when I go out that the name Times Beach comes up and people don't know about Times Beach. They've never heard of it. Probably you didn’t until you got to research it [...] It's coming up on 35 years since the dual disasters and I go to the schools and I talk to the students in the 7th and 8th grade; freshmen and sophomores in high school. And, the teachers do it because it was an environmental disaster that they want their students to know that happened. And that these things can happen. And it's part of history.”

A part of history just as long as there’s somebody still alive to tell it.

Outside/In was produced this week by:

Outside/In was produced this week by Zach Dyer with help from: Sam Evans-Brown, Maureen McMurray, Taylor Quimby, Logan Shannon, Molly Donahue, and Jimmy Gutierrez.

Special thanks to Ylan Vo and David Havlick for their insights on Superfund sites.

Music from this week’s episode came from Kimashoo Aoi, Ari de Niro, Podington Bear and Blue Dot Sessions.

Our theme music is by Breakmaster Cylinder.

If you’ve got a question for our Ask Sam hotline, give us a call! We’re always looking for rabbit holes to dive down into. Leave us a voicemail at: 1-844-GO-OTTER (844-466-8837). Don’t forget to leave a number so we can call you back.