Loser Wolves: A Cat Fancy

The Bengal cat is an attempt to preserve the image of a leopard in the body of a house cat… using a wild animal’s genes, while leaving out the wild animal personality. But is it possible to isolate the parts of a wild animal that you like, and forgo the parts that you don’t?

Can you have your leopard rosette, and your little cat too?

If you ever attend a cat show, be aware: if you ever hear a call “CAT OUT!,” stand still and let the owner catch the cat. Under no circumstances should you attempt to catch the cat yourself.

This advice can also be found in the brochure for the Catsachusetts Cat Club spring cat show, “The Final Catdown,” this year’s final event of the The International Cat Association (TICA) show season. Held in a cavernous ice rink in Cambridge, the show was a combination trade show slash cat breed competition. This is the world of the cat fancy — the term "fancy" essentially means “hobby;” it’s the term for pedigreed animal breeding. The Westminster Dog Show is the pinnacle of the “dog fancy,” but there’s also a horse fancy, butterfly fancy, guinea pig fancy, and so on.

After waiting in line to pay the $10 entry fee, visitors can weave through row after row of representatives from catteries across the country; cats who have been transported in intricate carriers festooned with patterned fabrics, pillows, toys, and even hammocks. Some were contenders for championship status; some angling for international awards; but participants also included families, entering their local purebred pets into friendly competition.

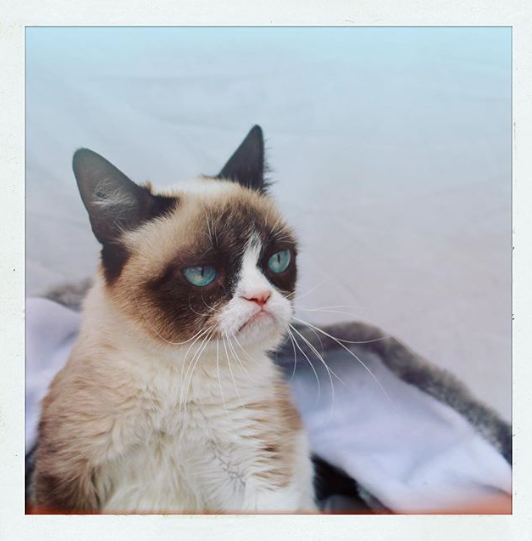

The main events took place in a series of judging rings at the edge of the arena: clusters of cages around a central table, complete with a scratching post. TICA recognizes 71 different breeds of cats, each with specific standards and qualities, and at the midday “Parade of Breeds,” the finest examples of many breeds were on display: the very handsome Norwegian Forest Cat, stocky and rugged with tufted ears; the Minuets, compact and short-legged; the sleek silver-grey Chartreux; and a Persian, a cloud of a cat with a decidedly grumpy expression reminiscent of Falkor the Luck Dragon.

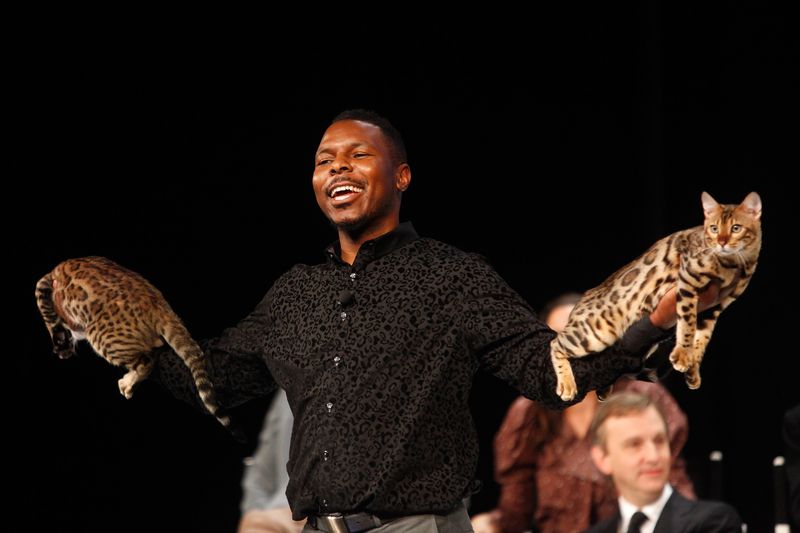

Prestige, anthony hutcherson's award-winning bengal via jungletrax bengal cats

But the reason we came to the show was to get a good look at the Bengal.

The Bengal is a striking creature: big for a house cat, muscular with wide paws, rounded ears, and, most importantly, rosettes, which are not just spots, but pale markings with a dark outline.

Bengals look like little leopards, which is precisely the point. The breed is the result of a hybridization between the ordinary house cat and the wild Asian Leopard Cat. TICA's breed standard stipulates that "the goal of the Bengal breeding program is to create a domestic cat which has physical features distinctive to the small forest-dwelling wildcats, and with the loving, dependable temperament of the domestic cat."

Bengals are a very popular breed: the most registered breed with TICA. There are Bengal breeders all over the the world, including Denise Eckhart, owner of Simia's Bengals outside of Boston. She has three females, including two who’d just given birth to litters when we visited this spring.

"In the right light, they have this gold dusted appearance. They kind of glitter," says Denise.

She also keeps a "whole male" (an unneutered breeding male) named Obi-Wan in an outdoor enclosure, separated from the unspayed females by a ten-foot fence. Wide-jawed, athletic, and adorned with leopard rosettes, Obi-Wan was handsome and impressive.

Denise has a wait list for her kittens. She's quoting 10-12 months at this point. The kittens sell for $1500 to 1800 as a pet; show rights and breeding privileges cost more.

Denise says she wouldn't consider raising any other breed of cat.

"There are so many things that I see in [Bengals] that are more wild than your average domestic," says Denise. "It’s so interesting: body language, the energy that is put into everything that they do, the crouching walking... it's more than your average. It's just more. The best way I can describe it is just more."

I came to Denise’s house skeptical not just of Bengals but of cats as pets, period. But Bengals are magnetic, and by the time we left, I found myself imagining what it would be like to have one of my own.

Cat breeding isn't without its problems, though. There are two basic critiques.

First, cats are often inbred, which can lead to challenges like compromised immune systems, breathing problems, susceptibility to kidney diseases or certain cancers, even skull deformations.

Second, shelters around the world are filled with cats. According to the ASPCA, 860,000 unwanted cats are euthanized every year. This is the “adopt, don’t shop” idea.

But beyond the ethics of purebred cats, what can we make of this impulse to bring the look of the wild into the home?

What is it about those leopard rosettes and those big eyes?

"The feelings that you get from being in the same room, sharing the same air, or that moment where you caress your hand down the back of an animal that looks wild. It kind of transcends time and space and reminds you why people wanted domestic animals to begin with," explains Anthony Hutcherson.

Anthony hutcherson at the new yorker festival in 2014 via getty images

Anthony lives outside of Washington, D.C. He makes a living as an event producer and speech writer, but Bengal breeding is his passion and full-time hobby. His cattery is called Jungletrax Bengal Cats.

Anthony fell in love with the idea of living with a wild cat when he was seven years old. Transfixed by his brown tabby cat, Whiskers, he began researching cats at his elementary school library.

"I started to compare Whiskers to wild cats like bobcats and jaguars and tigers, and became just enamored with ocelots," he says.

As Anthony got older, he wondered: why shouldn’t I have a wild cat? Laws and regulations vary by state, but in general, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service requires a permit to own a tiger — but there’s a loophole that makes it pretty easy, if expensive.

Anthony has a friend who bought a caracal, a species of wild cat that can get big, from a classified ad in the back of The Washington Post.

"She lived in Washington, D.C., in the middle of the city, and I went over to visit because it was so cool. And I met the cat as a kitten and I watched it grow up. This woman also had a Siamese cat," says Anthony. "Well, she came home one day and her caracal ate her Siamese cat and just left the head."

Anthony never owned a caracal, but he did live with an ocelot while studying abroad in Venezuela. When the ocelot actually peed on his suitcase, the smell was so strong, Anthony was forced to throw it away.

"Regular cat pee can rust metal. Ocelot pee can, I don’t know, corrode rock. It’s horrible," he says.

With that, Anthony realized that living with a wild cat might be a romantic idea, but the reality’s got a bad smell, at the very least. If Anthony wasn’t going to own a wild cat, what about the next best thing?

Sometime in the mid-80's, Anthony was grocery shopping with his mom. While he waited for her to check out, he flipped through the magazines by the register.

"And one was one of those grocery store tabloids that had an article and full color photographs about a woman who created a domestic cat that looked like a leopard, and I couldn't believe it. It had pictures of her holding one of them, holding one of the cats. It said they were $2000. And she called them 'leopardettes,'" recalls Anthony.

Anthony Hutcherson and Jean Mill

By a stroke of luck, Anthony, at 11 years old, had stumbled across the founder of what would eventually be called the Bengal cat. Her name was Jean Mill. Jean died this spring at the age of 92. We recorded our interview before she passed away.

"She is one of the most inspiring, terrific, and genius people I know," Anthony says.

Jean began her work with cat breeding when she went to college during World War II. She studied genetics.

"She didn't get a degree in it but she studied it there," says Anthony. "And her thesis was creating a panda cat. A cat that looked like a panda bear: black on some parts, white on others."

This cat eventually became what we now call the Himalayan. Jean liked the cat but eventually wanted something that looked wild.

Jean decided try hybridizing a domestic cat with a wild cat, selecting the Asian Leopard Cat, a small solitary nocturnal hunter native to southeast Asia. It’s about the size of an ordinary house cat but has more rounded ears, bigger eyes, and — most importantly — a pattern of rosettes on its coat. Jean ordered one from a wild animal import/export company, and one day, a kitten arrived on her front porch.

What is a cat breed anyway?

Jean's idea was incredibly murky, in a biological sense. She was attempting to create a new breed by crossing the cat with a different species.

"I mean, breed is, like... race. Honestly, it's a social construct. It really has no scientific definition," says Anthony.

In TICA, he explained, a breed is a group of animals of the same species that when bred together creates more that looks like them. Two Siamese cats make more Siamese kittens. Two Persians, Persian kittens.

It’s kind of a loose definition.

But the definition of species is slippery, too. The Endangered Species Act of 1973 defines a species as “any distinct population segment… which interbreeds when mature.” In other words, if they can mate and have offspring, they’re the same species.

But for a while now, scientists have acknowledged that those lines can be pretty blurry. For example, coyotes breed with wolves, and a horse can breed with a donkey, although their offspring, the mule, is sterile. It can’t reproduce.

And that is exactly what happened when Jean Mill crossed between the Asian Leopard cat and the domestic cat.

"In relative terms, they shared a common ancestor six million years ago. So when a Leopard cat breeds to a domestic cat, they are bridging a six million year divide," says Anthony.

More like seven million, but who’s counting?

Jean mill's article on the origin of the bengal

"The result of that is: only females are fertile. Males are sterile. So, you have to back-cross that female with domestic cat, and the offspring of those, only the females are fertile in that cross. And you have to back-cross those to a domestic male," explains Anthony.

Creating the Bengal was a slow process. Due to the nature of their anatomy, it is very challenging to artificially inseminate a cat. From our perspective, it's a little brutal: ovulation is stimulated by the barbs on the cat penis. So, when that first Asian Leopard cat arrived in a box on Jean’s porch, she had to get the cats genuinely interested in one another, which means raising them together from an impressionable young age.

Once they do finally have kittens, it takes four generations of crossing and back-crossing before the offspring are finally fertile in both sexes and can be bred with any domestic cat, which, Anthony says, qualifies them as a member of the domestic cat species and no longer a wild hybrid.

We’ll get back to that later.

This process took years. But of course, Jean was working in the dark. She didn’t know if she’d ever get to a breed. Plus, sometimes life got in the way.

"She got to the second generation but then tragedy struck her and she had to abandon breeding program and move to Southern California because her husband died," says Anthony.

Widowed and focused on taking care of her family, Jean gave up her hybrids to the San Diego Zoo. Years later, when she returned to the project in 1980, she had to start over. She managed to pick up a couple Asian Leopard Cat hybrids from a researcher named Dr. William Centerwall, who'd been researching Asian Leopard Cats' immunity to feline leukemia. His cats were just one step away from the wild, still sterile on the male side.

Once Jean had wild cat hybrids again, she launched into a search for the right domestic cats to incorporate into her breeding program. Her search became global when on vacation in India with her second husband, they visited the rhino pen at a zoo in Delhi. Anthony says this where Jean noticed a spotted, kind of sparkly cat, hunting mice near the rhino’s grain bin.

"And she was like, that one! She bred that cat to the ones she had and then she was able to get fertility in both sexes and that's where the Bengal breed comes from," says Anthony.

And thus, finally, the Bengal was born. But the world still had to accept it.

So, cat. Why are you in our houses? In our videos, on our interwebz?

But at that point, the concept of a cat breed was still a relatively new one. Not too long before?

How did we get here? via real grumpy cat

"There were no cat breeds, essentially," explains Abigail Tucker, a science journalist and the author of The Lion in the Living Room.

Like pretty much everyone we spoke to for this story, she loves cats. She’d written about jellyfish and wolves — animals far from her daily life — but then, her eyes fell on her cat, Cheeto, as if for the first time.

"I started looking at this little animal that lived in my house, at my feet, and next to me on the couch, and I started thinking that even though it seemed familiar to me in a lot of ways, I didn’t understand how it had come to cohabitate with me. That mystery kind of drove the reporting," explains Abigail.

If you were a human in the year 10,000 BCE and you had to make a bet on which of the wild animals around you would become a domestic pet, the Near Eastern wildcat would have looked like a terrible choice. Unlike the wild ancestors of dogs, which are pack animals, or those of sheep and horses, which are herbivores, the Near Eastern Wildcat is a solitary apex predator. It is 100% carnivorous, which means it competes with humans for a convenient source of protein — meat.

All this does not make the Near Eastern wildcat a good candidate for a pet. How did they make the transition?

Twelve to 14,000 years ago, humans were settling down into villages, starting to grow and store food, making piles of trash, and attracting rodents. All this new activity drew weasels, badgers, foxes, and other bold mesocarnivores. Tempted by all those delicious mice, these bold creatures got over their fear of being eaten by people.

"We actually see this in the archaeological record. I'm dealing with a site that’s about 11,600 years old in Turkey now," says Melinda Zeder, a senior scientist at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, who's been thinking about domestication for over 20 years.

The prevailing theory is that cats and dogs basically started out the same way.

"The less wary wolves, maybe the sort beta wolves in the pack, the loser ones, began to approach human settlements to feed off refuse," Melinda says.

There is a difference between tameness and domestication. Theoretically, you could train a wolf to be tame, but it would give birth to offspring that would be wild and would have to go through the same training process.

Domestication is something different -- but hard to pin down.

Melinda says she looks at it as a "co-evolutionary mutualistic relationship." With dogs, that relationship developed. Humans gave them dogs. They started being bred for sheep herding, hunting, driving sleds. Their appearance started changing. Charles Darwin described this as the “domestication syndrome:” a suite of features including curly tails, floppy ears, shorter teeth, and spotted fur.

"The interesting thing about cats is they don't exhibit a lot of these features common in the domestication syndrome," says Abigail Tucker. "We don't have lop-eared cats, we don't have cats with curly tails. We do have cats with spotted fur. But they do have the key trait that’s sort of associated with all domesticated animals and that is the reduced brain."

But even though we have a sense of what domestication feels and looks like, at a genetic level, it’s still pretty murky. Scientists are still determining what and where those genes are. Beyond the smaller brain, beyond the smaller brain, there’s a solid debate on how domesticated cats really are.

But if domestication is a spectrum from 1 to 10, perhaps dogs are at level 8, and cats maybe level 1 or 2. Humans never assigned cats jobs or selectively bred them for specific purposes. Instead, cats basically just hung out: hunting mice in barns, skulking in alleys, worshiped by the Egyptians, hated in the Middle Ages, but otherwise living on the periphery, more like presences than pets.

And so our relationship endured, unchanged.

The Victorians get involved

Queen victoria and turi, her pomeranian, c. 1895 via the royal collection trust

"The last two hundred - really one hundred and even, you could say, fifty years - have been the time of the rise of the house cat," says Abigail. "And this time of this animal’s sort of 'vertical hour' coincides with the fall of the rest of the cat family."

As humans took up more and more space, it became harder and harder to live with wild big cats, but it was comparatively easy to live with the domestic cat. Wherever humans went, cats quietly tagged along, mostly ignored.

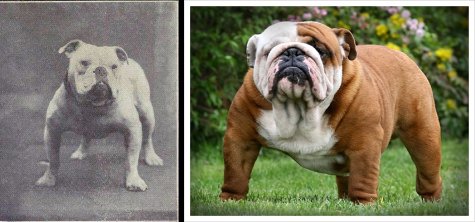

But in the mid-1800s, all that changed when the Victorians got involved and dramatically transformed our house pets. This is easy to see in dog breeds because, again, dogs were bred for hyperspecific jobs. There were hunting dogs with long noses and a keen sense of smell, or compact and quick breeds, good for catching rats.

But the Victorians turned dogs into fun-house mirror versions of themselves. They came through not only looking like cartoons, but sometimes actually non-functional without human interventions.

French bulldogs, for instance, are usually delivered by C-section because their heads are too big pass through the birth canal. Queen Victoria herself was particularly interested in Pomeranians, especially little ones, and the breed was miniaturized during her reign.

The English bulldog, before and after via science and dogs

The Victorians loved classifying and manipulating the world around them, which led to the concept of the pet show. There were shows for dogs but also rabbits, guinea pigs, and eventually, cats.

And thus, the cat fancy was born. The first cat show was held in 1871 at the Crystal Palace in London, infamous site of the first World's Fair.

But most pet cats still enjoyed the same quiet lifestyle, living outside or in the barn. But with the invention of kitty litter in 1947 and canned pet food shortly after, cats moved into the house.

"The invention of kitty litter was a catalyst, as you could say, for this change," says Abigail. "And also, I think these larger global trends, everything from urbanization, which led to people living in smaller spaces, more convenient for cats than dogs, to even things like the movement of women into the workplace."

the first cat show at the crystal palace via the book of the cat

The general trends of the 20th century created a perfect environment for cats to move into the house, which they did in massive numbers. The pet industry will gross an estimated $72 billion in the U.S. in 2018, according to the American Pet Products Association. It also estimates that there are 94.2 million pet cats in the U.S. - almost as many house cats as people with college diplomas.

This is a meteoric rise for the housecat, beyond any feline’s wildest dreams. With it came experimentation in breeding: the number of breeds rocketed from just over a dozen to forty, fifty, or more, depending on who you ask. It was in this crucible that the Bengal was born.

The Bengal hits the big time

Aside from Jean Mill, who retired from breeding when she was 80, Anthony Hutcherson has probably been the most vocal ambassador of the Bengal cat breed.

"You had to not only make cats and get attention of media, but you had to participate in the regular cat fancy. You had to go to cat shows. You had to have judges consider your plans," he says.

Anthony has not stopped pursuing Bengals since that moment in the grocery store when he saw Jean Mill advertising her leopardettes in the early 80s. He was part of a profile on wild cat hybrids in The New Yorker, appeared on the Martha Stewart Show, was written up by The New York Times and The Washington Post, and invited to the Westminster Dog Show with his cats in 2017. Plus, he’s been the chair of the Bengal Cat Breed section of TICA since 2009.

In the early years of the breed, even the cat fancy wasn’t too keen on the Bengal.

"We'd come to this cat show and the breeders of other breeds, Maine coons and Persians, didn't want Bengal breeders and their cats anywhere near them," Anthony says, recalling an early show. "They wanted us all in one section of the cat show because they said our cats smelled, their pee was different, and they made their cats act differently. That our cats weren’t really domestic cats."

Beyond cat urine, those comments have a disquieting whiff, given that ideas about species and breeding emerged during a time when the Victorians, and the Western World in general, were also exploring ideas of classifying humans. Anthony is black, and this is not lost on him.

An gathering of Bengal breeders in January 1996, Anthony Hutcherson and Jean Mill among them.

"They are intrinsically intertwined," explains Anthony. "The idea of what a breed is and what a species is, race, and culture."

Some regulators insist that even though Bengals can now reproduce with any domestic cat, they’re still a wild hybrid. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service makes you get a permit to import or export a Bengal outside the country, similar to an endangered species or wild animal. Seattle and New York City ban any hybrid cats, as does Hawaii. To Anthony, this feels like the infamous "one-drop rule," which said that any black ancestry made you a black person. Under certain regulations, one drop of wild cat blood, no matter how many generations back, makes Bengals still wild.

But in the pet breeding world, Bengal breeders have won the argument. TICA accepted the Bengal as a registered breed in 1986, and the Cat Fanciers' Association, another major pedigreed cat registry, finally followed suit in 2016.

So, who’s right? Is the Bengal domestic or still a wild hybrid?

For Tammy Thies, it's blurry. She’s the founder and executive director of WildCat Sanctuary in Minnesota. It’s a nonprofit sanctuary that houses big cats that used to be pets or those used for entertainment at roadside zoos and the like.

"We have over a hundred residents: tigers, leopards, cougars, lynx, African servals, Eurasian lynx, bobcats, jungle cats, and we also have Savannahs, Bengals, and Chausies. At least about 25% of our population are the hybrid cats," Tammy says.

The Bengal is not the only hybrid cat breed, although they are the most common. Keeping hybrid cats is expensive for the WildCat Sanctuary. Tammy says vet bills for hybrids are higher than for all the other big cats combined. Like a lot of purebreds, hybrid cats can be inbred. Plus, they can still act like wild cats.

"People spend $500, $1000, even up to $10,000 on a cat cat that's peeing all over their house. Domestic cats can even spray, that’s part of what they do, but we also see that they’re very vocal, they’re very active. And that's why people like them," Tammy says. "But I always kind of laugh. It's like having a two-year-old that never grows up. Bengals, the whole world revolves around them."

They can even get aggressive. Tammy says a lot of people buy Bengals for their looks but don’t understand the personality that comes with it. The most common line she hears is: the breeder never told me about this.

"The breeders get very mad at us and they say these are nothing more than domestic cats, you're ruining domestic cats," says Tammy. "And then it’s so funny because if you actually took the paperwork that they gave to their customer who gave them $1000 for a Bengal... that whole paperwork brags about how they just purchased a wild mix cat, and how it’s ancestry and it’s a lap leopard, and how special it is. These breeders can't have it both ways. They can't try and claim this is a 100% domestic cat but then to sell it, market the exotic-ness and the wild genetics of this animal."

Not all breeders are the same. But this is what makes Anthony Hutcherson's argument complicated. Sure, his hybrids might be twelve generations away from wild cats, but other breeders are still breeding the wild Asian Leopard cats back into the gene pool and calling them Bengals. They’re still messing with the recipe - introducing more wild genes back into the breed.

"Yes, there are still people doing that. It's a touchy subject honestly," says Anthony. "Because folks like me think it perpetuates this idea that it's not possible to create a cat that looks like a little leopard without breeding it to leopard cat or a wild animal.

So if you’re Joe Cat Fancy looking for a Bengal breeder on Google, it can be hard to know what you’re going to get.

Wildcats, Everywhere and Nowhere

But to me, one of the most interesting aspects of this conversation is also the most basic part of it. Can you isolate the parts of a wild animal that you like, but forgo the parts that you don’t? Can you keep the leopard rosette, but leave out the leopard personality?

"What can be troubling about some of these hybrid wild domestic cats is... it's again this slightly Victorian impulse that we are the lords of the universe, and we’re gonna have a little lion purring in our lap, enjoying their company while blissfully going about our business and killing off all the real wildcats in the world," says Abigail Tucker.

"Sometimes these hybrid cat breeders will argue, 'well, but these cats are ambassadors for animals like lions and tigers,' but I'm not sure that's always true," explains Abigail. "I mean, having a cat of any kind is at heart a selfish act. We have cats because we like cats."

Stereographic image titled, "Famous 'man-eater' at Calcutta - devoured 200 men, women and children before capture - India. photo by James Ricalton, public domain.

We love lions and tigers. We want leopard print on our cats and on our leggings. We name our cars and our sports teams after big cats. But we also have a really hard time living with the real thing. Big cats needs lots of space and isolation. With habitat loss, climate change, hunting, plus millennia of human-cat conflicts, we are, by and large, witnessing the near total decline of big cats around the globe. There is just one jaguar known to be alive in the wild in the United States, and less than four thousand wild tigers alive globally, far fewer than the number of tigers captive in the United States alone.

All these different portrayals of leopards, including the Bengal, sound like different iterations of the same desire. They are ways to be close to the parts of wildness that are easy to live with, while leaving out the parts that are hard - like leaving enough space for them on earth. As tigers and leopards are vanishing, they’re also growing more and more visible, and more and more sale-able.

"I just feel that the big cats' mystique is sort of like the last thing they've got going for them, so for us to take that from them and make it commonplace," says Abigail. "They’re sort of commodifying something that is the wildest thing that we have left on the earth."

Outside/In was produced this week by:

Outside/In was produced this week by Justine Paradis and Sam Evans-Brown with help from: Erika Janik, Maureen McMurray, Taylor Quimby, Hannah McCarthy, and Jimmy Gutierrez.

Special thanks to Judy Sugden, Leslie Lyons, Katie Lytle, and Carla Bizzell.

Music from this week’s episode came from Jahzaar, Steve Coombs, Kevin MacLeod, Tyler Gibbons, Podington Bear, and Blue Dot Sessions.

Our theme music is by Breakmaster Cylinder.

If you’ve got a question for our Ask Sam hotline, give us a call! We’re always looking for thorny trails to follow. Leave us a voicemail at: 1-844-GO-OTTER (844-466-8837). Don’t forget to leave a number so we can call you back.