It Was the Ladies Who Hugged the Trees

On May 21, 2021, an influential environmental activist died of Covid-19 and you probably didn’t hear about it. Sunderlal Bahuguna’s passing didn’t make the major news outlets in the US, but it was a big deal in India, where he was the renowned leader of the 1970s Chipko movement against deforestation.

Chipko is a Hindi word for “hugging”, but according to Bahuguna, he was just the messenger of the movement. “It was the ladies who hugged the trees,” he said.

This story is about the life and legacy of Sunderlal Bahuguna, and the tree huggers that saved India’s forests.

Featuring: Haritima Bahuguna

Love Outside/In? You’ll love the Outside/In newsletter! Sign-up here.

The beginnings of the movement

The Chipko movement began in 1973 in Uttarakhand, a rural, mountainous region in northern India. Many men in Uttarakhand left for jobs in the towns and cities, and women stayed behind, depending on the forests for their livelihoods. They gathered firewood for heating and cooking, grass to feed their livestock, and wild medicinal herbs.

But as more trees were logged for manufacturing railroad ties, furniture, paper, and sports equipment like tennis rackets, local women had to walk further and further to get their daily necessities.

The tipping point came when the government granted access to a sporting goods company to cut hundreds of trees, just after denying a local co-op’s request to cut down just ten trees.

The companies sent their lumbermen to cut the trees, but the villagers confronted them in the forests, and stood their ground.

While this first confrontation was mostly men, most of the subsequent confrontations were led by women.

Bahuguna’s life

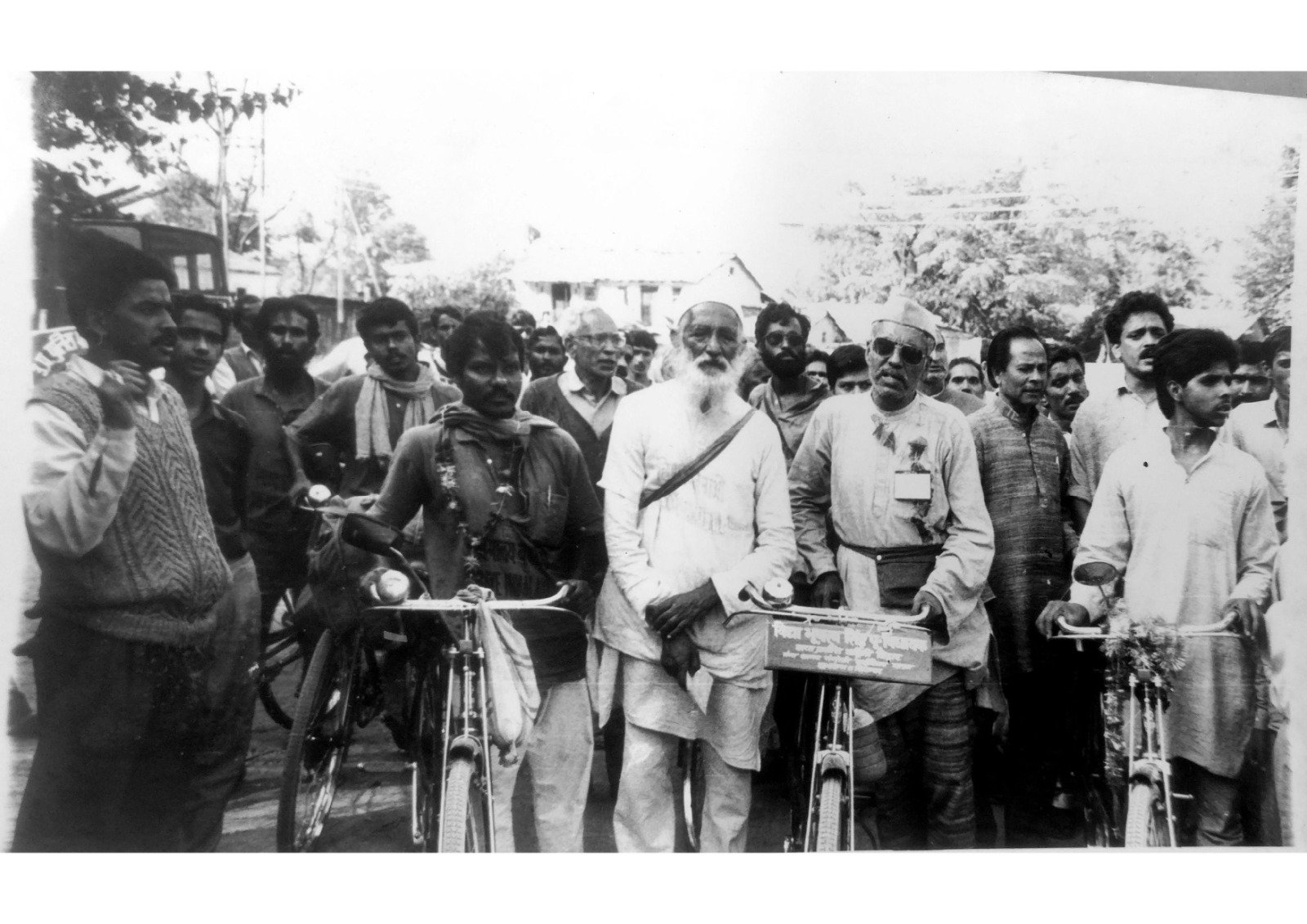

Bahuguna is well-known as the face of the Chipko movement because he was its messenger. He spread word of the Chipko movement on foot, including a 4,870 kilometers tour (roughly the equivalent of walking from Boston to Seattle) in the early 80s.

“I am simply the messenger of the movement. It was the ladies who hugged the trees. I simply went with this message from one village to another,” he said in an interview.

“He was actually instigated by Gandhi, who actually told him that if you have a message you cannot [concentrate it] in an area and expect it to be bigger. So they advised him to travel as much as he can and spread the message,” said Haritima Bahuguna, Sunderlal’s granddaughter.

Sunderlal Bahuguna had been influenced by Gandhian principles of civil disobedience since the young age of 13, when a disciple of Mahatma Gandhi walked up to him and his friends on the street, carrying a big box with a charkha, a kind of loom or spinning wheel, inside.

This was back in 1940, when India was still under British colonial rule and the government suppressed the weaving of clothes by the Indian people.

“And he said, ‘this is the weapon with which we are going to produce our own clothes,’” said Haritima.

The encounter inspired the young Bahuguna. After Indian independence, he joined the National Congress in 1948.

As a politician, Bahuguna met a woman named Vimla Behn, a Gandhian social activist dedicated to the education of village women. Family members of Bahuguna and Vimla Behn arranged for them to be married, but Vimla Behn said she’d marry him on one condition: he must leave politics and settle in the hills, where together, they’d help people.

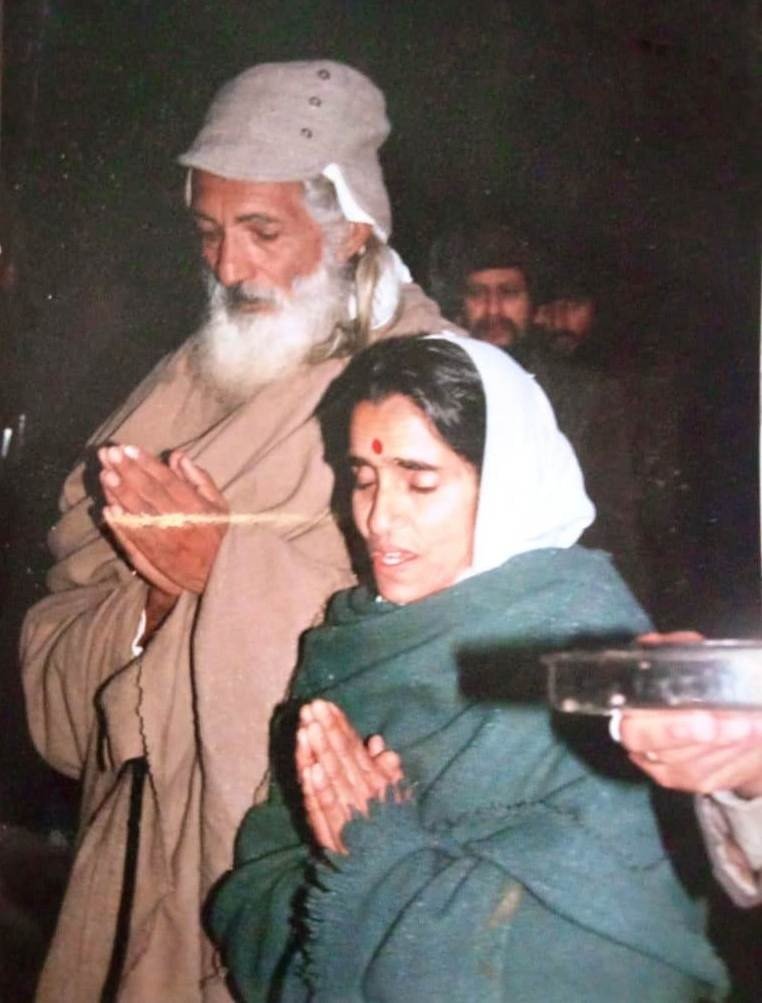

He agreed. After they were married in 1956, they moved to a remote village in Uttarakhand, where they set up an ashram that wasn’t restricted by caste or gender. An ashram is a spiritual retreat community in Indian religions, and this particular ashram was dedicated to the education of village people. Their ashram became the meeting grounds for many Gandhian activists to discuss issues like alcoholism, casteism, gender discrimination, and, increasingly, deforestation.

In 1981, the Indian government offered Bahuguna one of the highest civilian honors in India, the Padma Shri award. But he refused it.

“He refused because even then, the government has not banned forest deforestation in Uttarakhand. He's like, ‘I do not deserve any honor or award until what I want is not done,” said Haritima, Bahuguna’s granddaughter.

Less than two months after Bahuguna’s refusal of the award, the government finally banned all logging above a thousand meters in Uttarakhand. U.N. data shows that around this time, India’s forest coverage turned from a steady decline, to a steady increase that continues to this day. Chipko is also at least partially credited for the creation of a completely new government agency in 1980 called the Ministry of Environment and Forests.

A lover of music and poetry, his granddaughter recalled that Bahuguna would often recite a verse from the Bhagavad Gita.

“It means… do your work, do not be concerned about the results of it,” Haritima said. “He always used to tell me that it's my job to do my job to the best of my potential... and that whatever it is that I get, that's not in my hand, that someone else decides.”

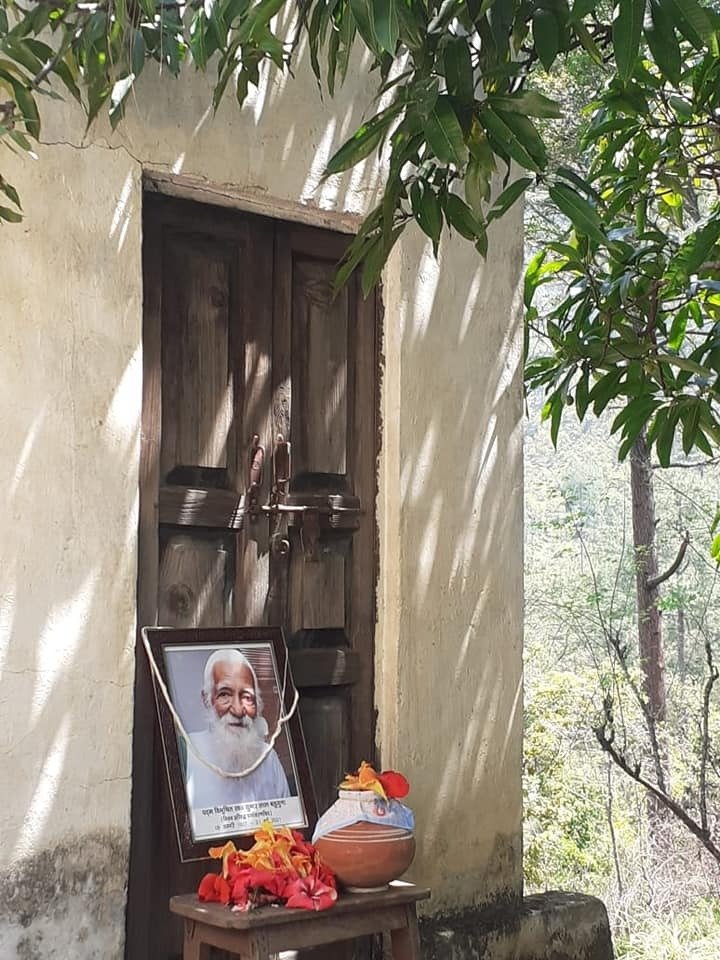

Sunderlal Bahuguna died on May 21st, 2021. A memorial service was held for him on June 5th, which is World Environment Day, a day established by the U.N. to encourage awareness and action to protect our environment.

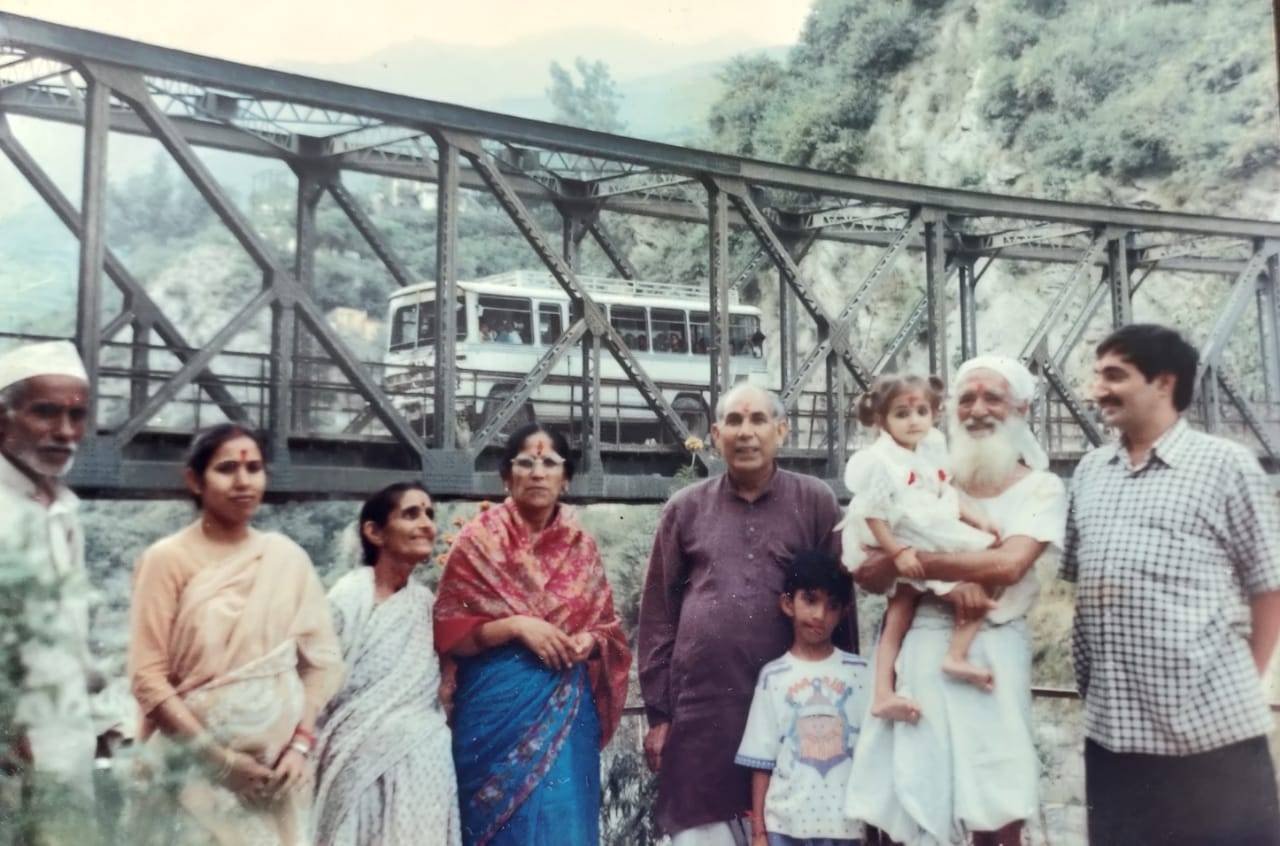

(Photos courtesy of Haritima Bahuguna)

Links

On The Fence: Chipko Movement Re-visited

Credits

Reported and produced by Felix Poon

Host: Justine Paradis

Edited by Taylor Quimby

Additional editing by Justine Paradis, and Erika Janik

Executive producer: Rebecca Lavoie

Mixed by Felix Poon

Theme: Breakmaster Cylinder

Additional music by Saumya Bahuguna, Samuel Corwin, and Blue Dot Sessions

Audio Transcript

Note: Episodes of Outside/In are made as pieces of audio, and some context and nuance may be lost on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors.

Justine: This is Outside/In, a show about the natural world and how we use it. I’m Justine Paradis.

On May 21, 2021, a man by the name of Sunderlal Bahuguna. Not many in the US noticed. His passing didn’t make the news in any of the major outlets in the US. But it got extensive coverage in India.

[News montage of death, and legacy in the Chipko movement]

Justine: The reason Bahuguna’s death was big news there is because he was the most well-known leader of a movement in India called the Chipko movement that took place in the 1970s in a region of the Himalayas. And that was a watershed moment, inspiring greater environmental consciousness across India, as well as other environmental movements across the world.

Our producer, Felix Poon, tells this story, about the life and legacy of Sunderlal Bahuguna.

Felix: When I first learned about the Chipko movement, I thought, this is an amazing story, how come I’ve never heard about it? I wasn’t alone. When I asked other people in the US if they’d ever heard of it, they said the same thing, they’d never heard of Chipko, or Sunderlal Bahuguna. And I wonder if it’s because Chipko activists don’t fit the stereotype of who an environmentalist is.

[MUX in]

most of them were rural poor women, living subsistence livelihoods. They took on a powerful government agency that was in bed with big for-profit companies. And they won -- they got the national government to ban all logging in their region above a thousand meters. And The national government created a new Ministry of Environment and Forests. According to UN Data, India reversed a century-old pattern of deforestation, and started a steady increase in forest coverage that's still increasing to this day.

So, who was this man, Sunderlal Bahuguna, that led this movement?About a week after he passed away, I spoke with one of his granddaughters, Haritima Bahuguna. I asked Haritima to tell me about one of her earliest memories with him.

[MUX out ]

Haritima: every morning, early morning, he used to ring a bell, above my head until I wake up and I used to get so irritated with that and used to sing a poem with that that used to talk about how good the morning is. And every evening, we used to have the Ganga Arthiv

Felix: The Ganga Aarti, is a prayer song, it’s ritual offering to honor the Ganges river

[mux fade up]

Felix: This is the Ganga Aarti sung by Haritima’s sister Saumya Bahuguna.

Haritima: he was very fond of poems and songs. And he most of the time, because I think because I think because of Chipko, he got so used to communicating his things through songs and poems that even with me sometimes he used to, yeah. Give me answers in the form of poetry.

[MUX post and out]

Felix: It all began for the Chipko movement in the foothills of the Himalayan mountain range, in a region called Uttarakhand. Most of the men in this area had left the mountain villages for jobs down in the towns and cities, leaving the women to take care of their homes and children. And to do that, they depended on the forests -- they harvested firewood for heating and cooking, grass to feed livestock, and they even got their drinking water and medicinal herbs from the forests.

[ambi + sawing]

But... the forests were disappearing -- trees were logged to make railroad ties, furniture, and sports equipment. And so as time went on with this deforestation, these women were having to walk further and further just to get their daily necessities. And this is difficult work, trudging miles and miles, hauling heavy bundles of wood

The tipping point came when the government granted access to a sporting goods company to cut hundreds of trees, when they had just denied a local co-op’s request to cut down just 10 trees. This infuriated the co-op members. So when the company sent their lumbermen to cut the trees in the forest, the villagers confronted them -- and this first confrontation was led by the men from the local co-op. But most of the confrontations after that were led by women.

Woman: the forest guys were shouting at us, “we’ll put you in jail, why are you talking?” We women laid down, didn’t let the forest guys go ahead. They said, “what do you think, we’ll strip you naked and send you.”

Felix: This is a clip from a documentary called On the Fence, which you can watch on YouTube.

Woman: “Go on you lumbermen, go, leave the jungle forest, leave the axe, save the forest. That’s the song we sang. Come sisters come. We’ll save the forest. We’ll grab and bring the axe and saw, we’ll save our forests.

[singing]

Haritima: So Chipko in Hindi means hugging.

Felix: This is Haritima again.

Haritima: So they used to hug the trees and they used to say, if you're going to cut this tree, you're going to cut me as well, because it has got equal life than I have.

Sunderlal: I am simply the messenger of the movement. It was the ladies who hugged the trees. I simply went with this message from one village to another,

Felix: This is Sunderlal Bahuguna, interviewed for a documentary called Apiko - to embrace. The audio isn’t great, he said he’s simply the messenger of the movement, and it was the ladies who hugged the trees, not him.

Sunderlal: then I walked from Kashmir to Kohima, the whole Himalayan region.

Felix: He spread the message on foot, walking nearly 5 thousand kilometers. That’s like walking from Boston to Seattle

Sunderlal: without any money in my pocket, whatever people give, I lived upon that

Haritima: he was actually instigated by Gandhi who actually told him that if you have a message, you cannot concentrated in an area and expect it to be bigger. So they advised him to travel as much as he can and spread the message.

[Mux]

Felix: Bahuguna was influenced by Ghandian principles since the young age of 13. He and his friends were playing on the street when a disciple of Mahatma Ghandi came up to them carrying a big box. And so they were like, hey what’s in the box? So he opens the box, and says

Haritima: this is the weapon with which we are going to produce our own clothes

Felix: It was a charkha, or a kind of loom or spinning wheel. This was back in 1940, when India was still under British colonial rule -- which was suppressing Indian people from weaving their own clothes. So the charkha became an important tool for the independence movement,

Haritima: we are not going to be dependent on the British and we’re going to force them to go out of the country and make us independent.

Felix: This was Bahuguna’s first encounter with the independence movement, and it inspired him to read Gandhi’s books, and learn more from the disciple.

After Indian independence, Bahuguna got into politics, and joined the National Congress in 1948.

And it was as a politician that Bahuguna met a woman who would change the trajectory of his life. Vimla Behn was a Ghandian social activist dedicated to the education of village women. Family members of Bahuguna and Vimla Behn thought that arranging their marriage would be a smart move for Bahuguna’s political career. Vimla Behn wanted to marry Bahuguna, but she had a completely different idea for their marriage. So she said she’d marry him, but only on one condition.

Haritima: the only condition that I'm going to marry you is that you'll have to leave politics and settle in the hills and help people in the hills with me.

[Mux]

Felix: And that’s what he did. They got married in 1956, and Sunderlal Bahuguna left politics. They moved to a remote village with his wife Vimla Bahuguna, to set up an ashram dedicated to the education of village people with no restrictions of caste or gender.

an ashram is a spiritual retreat community in Indian religions, and this particular ashram would become the meeting grounds for many Ghandian activists to come and talk about the biggest issues affecting village people -- things like alcoholism, casteism, gender discrimination, and more than ever, deforestation.

They talked about how there used to be way more natural resources in UK, like indigenous trees, fertile fields, and grasslands, but so much of these were replaced with pine tree plantations, these monocultures that might be great for commercial logging, but are terrible for the local ecology. For example, Pines don’t soak up rain water in the same way thatthe indigenous trees did. And so the result was more environmental degradation, like soil erosion, floods, land slides, and drought.

And this all impacted women the most. Environmental scholar and activist Vandana Shiva, wrote that women were the foundation of the Chipko movement. They were the ones feeling the devastating impacts on a daily basis. So they didn’t want any trees to be cut. But the men in the Chipko movement still wanted to cut trees, for economic development. They just wanted to control that locally and on a small-scale.

It was clear to Shiva, which side Bahuguna stood on.

Hannah McCarthy as Shiva: Bahuguna has been an effective messenger of the women’s concern.

Felix: This passage is from Shiva’s book, Staying Alive: Women, Ecology, and Development.

Hannah McCarthy as Shiva: It is largely through listening to the quiet voices of the women during his padyatras (spiritual tours on foot) that Bahuguna has retained an ability to articulate the feminine-ecological principles of Chipko.

[Mux in]

Felix: Women were the backbone of the Chipko movement, and this was true of Sunderlal’s wife, Vimla, as well. He said he was just the flag of the movement, and Vimla was the staff that held him up.

Bahuguna became the face of the movement to the Indian national government, The national government offered him an award for his activism in 1981.

Felix: The padma shri award, one of the highest civilian awards in India.

He refused the award.

[mux out]

Haritima: But he refused because even then, the government has not banned forest deforestation in Uttarakhand.

Felix: Here’s Haritima again.

Haritima: He's like, I do not deserve any honor or award until what I want is not done

Felix: Less than two months after Bahuguna’s refusal of the award, the government finally bans all logging above a thousand meters in Uttarakhand. UN data shows that around this time, India’s forest coverage makes a turn at around this time, and The country goes from a steady decline in forest coverage, to a steady increase. And that increase is still going today.

Felix: What do you think is your grandfather's legacy? What is Sunderlal Bahuguna’s legacy?

Haritima: Legacy. Well, it’s kind of a lot, putting it into words is actually interesting.

Felix: I know this is kind of a pithy question, trying to encapsulate a man’s life in a couple of neat sound bites. It’s the sort of thing that people ask after someone has passed -- but the best answers might not fit that neatly into the history textbooks.

Haritima: he was majestic The way he used to speak the things that I’ve heard from him, I have never heard such things from anyone else, he had that very different charisma in him.

Felix: There’s one story about Sunderlal Bahuguna’s life that really stuck with me. Besides his major victories in Chipko, the thing he’s really known for in India was his fight against the construction of the Tehri Dam, which wasn’t just because he cared about the environment. It was also because he was from there.

Haritima: He actually grew up there. Whatever he did, he did. To save his community, to save his environment

Felix: Bahuguna was jailed several times for protesting, and he fasted for nearly 75 days in protest of the dam. Eventually, his efforts did prompt India’s prime minister to review the project. But he ultimately lost. The supreme court ruled that construction of the dam could go ahead.

Haritima: My grandfather actually stayed there until his house was literally drowned

Felix: Bahuguna refused to leave until all the town’s people were safely resettled in new homes.

Haritima: he was so adamant in not leaving. He's like, it's fine if I die, I'll die with this.

Felix: He and his wife Vimla were the last people left in the town, and the water was literally rising and submerging their house

A boat had to go and rescue them.

Bahuguna was heartbroken by this. He shaved his head, and his beard in mourning his loss. Haritima says he'd never done that before.

Some would say his activism against the dam was a failure. But, we can look to Haritima’s memories of him to know what he thought. According to Haritima, he often recited a verse from the Bhagavad Gita.

Haritima: in Hindi, they say Garnkar falkee jan tah mand kar. It means that do your work, do not be concerned about the results of it. And he used to always used to tell me that it's my job to do my job to the best of my potential that I can and that I will, whatever result I get, that's not in my hand, someone else decides that.

Felix: Sunderlal Bahuguna died on May 21st, 2021. A memorial service was held for him on June 5th, which is World Environment DaY.

[Theme mux]

a day established by the UN to encourage awareness and action to protect our environment. World Environment Day was established in the early 70s, the same time that the Chipko movement began.

Justine Paradis: That was producer Felix Poon on the life of Sunderlal Bahugana. Excerpts of Sunderlal Bahuguna and sounds from the forest came from the documentary, the Axing of the Himalayas, which is available to watch on YouTube.

CREDITS

Justine: That’s it for Outside/in. This week’s episode was produced and mixed by Felix Poon, edited by Taylor Quimby, with additional editing help from Erika Janik, and me, Justine Paradis. Rebecca Lavoie is our executive producer.

Special thanks to Professor Emeritus George James of the University of North Texas for his expert knowledge on Sunderlal Bahuguna and the Chipko Movement. Thanks also to Hannah McCarthy, who read an excerpt of Vandana Shiva’s book, Staying Alive: Women, Ecology, and Development.

Music in this episode was from Samuel Corwin, and Blue Dot Sessions. Saumya Bahuguna sang the Ganga Aarti. Our theme music is by Breakmaster Cylinder.

Outside/in is a listener-supported podcast from New Hampshire Public Radio - you can support the show by donating at outsideinradio.org.