Holy Scat! Why Antlers Are Freaking Amazing

Antler tissue is the fastest growing animal tissue on the planet. It grows faster than a human embryo, faster even than a cluster of cancer cells. On a hot summer day, some people say antlers can grow as much as one inch per day! And buried inside them is a cocktail of nutrients that both animals and humans are itching to get their paws on.

In summary: Antlers are freaking amazing.

In this episode of Outside/In, we’ve invented a new segment just to highlight the magic of antlers. We’re calling it Holy Scat! and it’s our way of exploring all the things about the natural world that make us totally geek out.

For our inaugural adventure, we’ll learn about how antlers grow so fast, meet a collector who covers hundreds of miles searching for them, AND find out why scientists hope they could unlock new treatments for osteoporosis. Plus, we’ll tell you a whole herd of awesome deer factoids, and answer the eternal question: are Santa’s reindeer males or females?

Love Outside/In? You’ll love the Outside/In newsletter! Sign-up here.

Featuring Henry Ahern, Will Staats, Brendan Lee, and Tomas Landete -Castillejos. Special thanks to Chris Martin and Dave Anderson of Something Wild, who inspired this episode!

Links

Check out the episode of the NHPR podcast Something Wild that inspired this story!

Stanford scientists identified genes behind rapid antler growth. Read more here.

Watch a video describing the research on glioblastoma cells.

Good footage of an antler shoving match.

Graphic Video Warning! If you want to see what an emergency velvet antler amputation looks like, here you go.

Reporting on MMA Fighter George Sullivan’s one year suspension for the use of Velvet Antler supplements

Is the Coronavirus in Your Backyard? A New York Times report on coronavirus in animal populations (and especially, in deer)

An article from Smithsonian detailing what may be the first case of coronavirus to spread from a deer to a human

Credits

Produced and researched by Jessica Hunt and Taylor Quimby

Executive producer: Rebecca Lavoie

Edited by Taylor Quimby and Rebecca Lavoie

Mixed by Taylor Quimby

Additional editing: Felix Poon and Nate Hegyi

Special Thanks to Cindy Downing.and David Hewitt

Theme: Breakmaster Cylinder

Additional music by Arthur Benson and Claude Signet

If you’ve got a question for the Outside/In[box] hotline, give us a call! We’re always looking for rabbit holes to dive down into. Leave us a voicemail at: 1-844-GO-OTTER (844-466-8837). Don’t forget to leave a number so we can call you back.

Audio Transcript

Note: Episodes of Outside/In are made as pieces of audio, and some context and nuance may be lost on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors.

Taylor Quimby: Is this it? No. Ok. Looking for deer, looking for deer, looking for deer…

Jessica Hunt: Hello, I’m Jessica Hunt…

Taylor Quimby: I’m Taylor Quimby.

Jessica Hunt: ...and on a single digit day in January, we drove to a very unusual kind of farm.

Taylor Quimby: God, they're all packed together like penguins.

Jessica Hunt: It was a deer farm.

Jessica Hunt: They're looking at us.

Taylor Quimby: Ok. All right, keep your eyes on the road here.

Jessica Hunt: I can't, I can't. Oh my God.

Taylor Quimby: There are over four-thousand deer farms in the United States. Most of them raise white-tailed deer. Here, at Bonnie Brae Farm in Plymouth, New Hampshire, it’s their European cousins - the slightly larger red deer.

[car door/hello tape]

Jessica Hunt: About three-quarters of the farm’s profits come from selling venison. But the other twenty-five percent comes from what is arguably, one of the most incredible sets of bones on Earth.

Antlers.

Jessica Hunt: That’s amazing. After a year’s worth of growth, they’re this big.

[mux]

Jessica Hunt: Antler tissue is the fastest growing animal tissue on the planet. It grows faster than a human embryo. Faster than a cluster of cancer cells.

Taylor Quimby: That’s absurd.

Jessica Hunt: It is.

Taylor Quimby: In one season, a mature deer can grow 40 pounds of antler, and not long afterwards toss them on the forest floor like a beer can thrown out of a Ford F150.

Jessica Hunt: I don’t even know what a Ford F150 is.

Taylor Quimby: It’s a truck!

Henry Ahern: They're the only mammal that grow an appendage, and it falls off every year and they grow another one like your arm falling off every year and growing a new arm.

Jessica Hunt: They grow so fast… you can practically watch it happen.

Henry Ahern: And it will grow - on a nice, hot day you can actually go out in the morning and go out in the evening and you'll see that it has grown. It'll grow an inch or more in a day.

Jessica Hunt: Okay, so maybe not quite that much for deer, but for moose and elk - yeah, scientists say up to an inch per day.

Taylor Quimby: An inch a day?

Jessica Hunt: One inch..

Taylor Quimby: A day.

Jessica Hunt: Per day.

[Holy Scat Stinger]

Taylor Quimby: Today on Outside/In we take a look at the incredible, EDIBLE ungulate antler….a bone so wild, we’ve invented a new segment of Outside/in just to highlight it.

Jessica Hunt: We’ll learn about how antlers grow, find out whether Santa’s reindeer are cows or stags… meet a collector who scours the woods for shed antlers… and find out why scientists think antlers could unlock new treatments for diseases like osteoporosis.

Taylor Quimby: And Jessica I’m counting on you to do the work here because I’m just along for the ride.

Jessica Hunt: It’s always the way.

[mux fade]

Jessica Hunt: So I would love to just go out there and look at them and talk to you.

Henry Ahern: Oh we can do that. And I have antlers here. Now most of the deer at this time don’t have antlers on them, except the yearlings, the spikers still have them.

This is Henry Ahern, who runs Bonnie Brae Farm, now in it’s 28th year. The place is absolutely littered with antlers. They hang off the walls of his barn, line the inside of a big walk-in cooler, and there are two tall piles of them in the greenhouse near where we parked.

Jessica Hunt: How much do these weigh?

Henry Ahern: This is 12. This it may have dried out somehow, but this is about 12 pounds on a side, so it's about twenty four pounds.

Inside the farm’s tiny store, there’s a shelf of locally made jams and jellies, and in the back, racks and racks of old computer parts.

Henry also works as a computer consultant - a job he’s been doing since computers were basically giant calculators.

Jessica Hunt: So you’re our Steve Jobs.

Henry Ahern: I know Steve Jobs. I knew Bill Gates too, I’ve shaken hands with him and talked to him because… Bill Gates is a weird guy.

Which is why Bonnie Brae Farm may host the only retail establishment where you can buy a shoulder of venison, a jug of maple syrup, and a lightning to USB cable all at the same time.

Henry Ahern: I'm an apple computer dealer and deer like apples, so it only fits, right?

[mux]

Jessica Hunt: Ok, Taylor - are you ready for some antler facts?

Taylor Quimby: Hit me.

Deer and moose are all a part of the family Cervidae. There are more than 50 separate species on Earth - all but one have evolved to sport antlers.

Taylor Quimby: Ooh. Sucks to be those ones.

Jessica Hunt: Sucks to be that one, I’m like, what why?

Taylor Quimby: Because they’re left out, they must be sad!

Jessica Hunt: Maybe they’re evolved not to sport antlers.

Taylor Quimby: Okay, fair enough.

Typically, it’s the males that grow antlers. Caribou - which are another name for reindeer, by the way - are the only exception

The biggest antlers in history belonged to an extinct deer called Mega LOSS eros giganteus, [good name] , yes….better known as the Irish Deer. Their antlers could weigh as much as 80 pounds each and together, were as wide as two twin mattresses laid end to end.

Taylor Quimby: The other way to think about this is, as wide as a basketball hoop is tall.

Jessica Hunt: That’s crazy.

Taylor Quimby: How would you get anywhere?

Jessica Hunt: I can’t imagine.

Taylor Quimby: That sounds awful.

[mux swell]

Jessica Hunt: When a new pair of antlers start growing, they look like stuffed animals- because they're covered in a fuzzy coating of skin called velvet.

Those velvet antlers are where the magic happens. They’re so full of blood vessels that when they're growing, they’re warm to the touch.

Taylor Quimby: Like an actual limb - as opposed to a horn I guess.

Jessica Hunt: Exactly. They’re also packed with nerves - so antlers at this stage are incredibly sensitive. Except for the layer of fuzz, they’re basically exposed cartilage.

Taylor Quimby: Oof, that sounds scary. I bet they’re very careful not to bump them against things.

Jessica Hunt: Yes, absolutely. In the fall, the antlers start to harden into bone. Afterward, wild deer rub them against trees to scrape the skin off.

[sound of deer rubbing antlers against a tree]

Taylor Quimby: I looked up a video of this, it looks like they’re itching it off, it looks super-itchy at this stage. Like a scab.

[sound of deer rubbing antlers against a tree]

At Bonnie Brae farm, the deer never get to that stage. That’s because antlers are most valuable to humans before they’ve hardened.

Henry Ahern: All the hair what people call velvet gets actually scraped off and thrown away. That's not the product we're after. What we’re after is the inside, where all the nutrients, minerals, stem cells. I’ve got a brochure for you…

Since you might be wondering, I’ll tell you - farming velvet antlers means cutting them off of living animals. When we went out with Henry Ahern to see his deer, all the stags had already had theirs cut off - all that was left was a pair of boney stumps on their foreheads.

This makes farms like these a little controversial - after all, as we said, velvet antler is essentially a living appendage - packed with nerves and blood.

Henry Ahern: When we cut if off, it does bleed. We have tourniquets on it, local aesthetic that meds it like pulling a tooth, but it does bleed.

The American Veterinary Medical Association says that anesthetics are effective for numbing the pain - but obviously cutting off antlers causes the animals some stress. How much is the question.

Henry Ahern: The thing is the deer are used to losing their antlers. When they fall off in the spring, they bleed. You look at this button, there’s blood on it from when it fell off.

Henry showed Taylor and I a couple antlers in his office. The first one is from a hard antler, the kind we’re using to seeing on prize bucks, after they’ve scraped away the velvet. If you look closely, there are smooth channels carved along the length of each beam.

Henry Ahern: and these lines that you see on it are actually the blood lines where the blood flows were

The other was a velvet antler, cut from one of his deer just before it started to mineralize.

He keeps it in a freezer, so it’s cold and feels a little wet from the condensation.

Henry Ahern: It’s frozen now so you can’t bend it, but when we go to take it off you can bend it.

Jessica Hunt: Wait, what?

Henry Ahern: It’s still moveable.

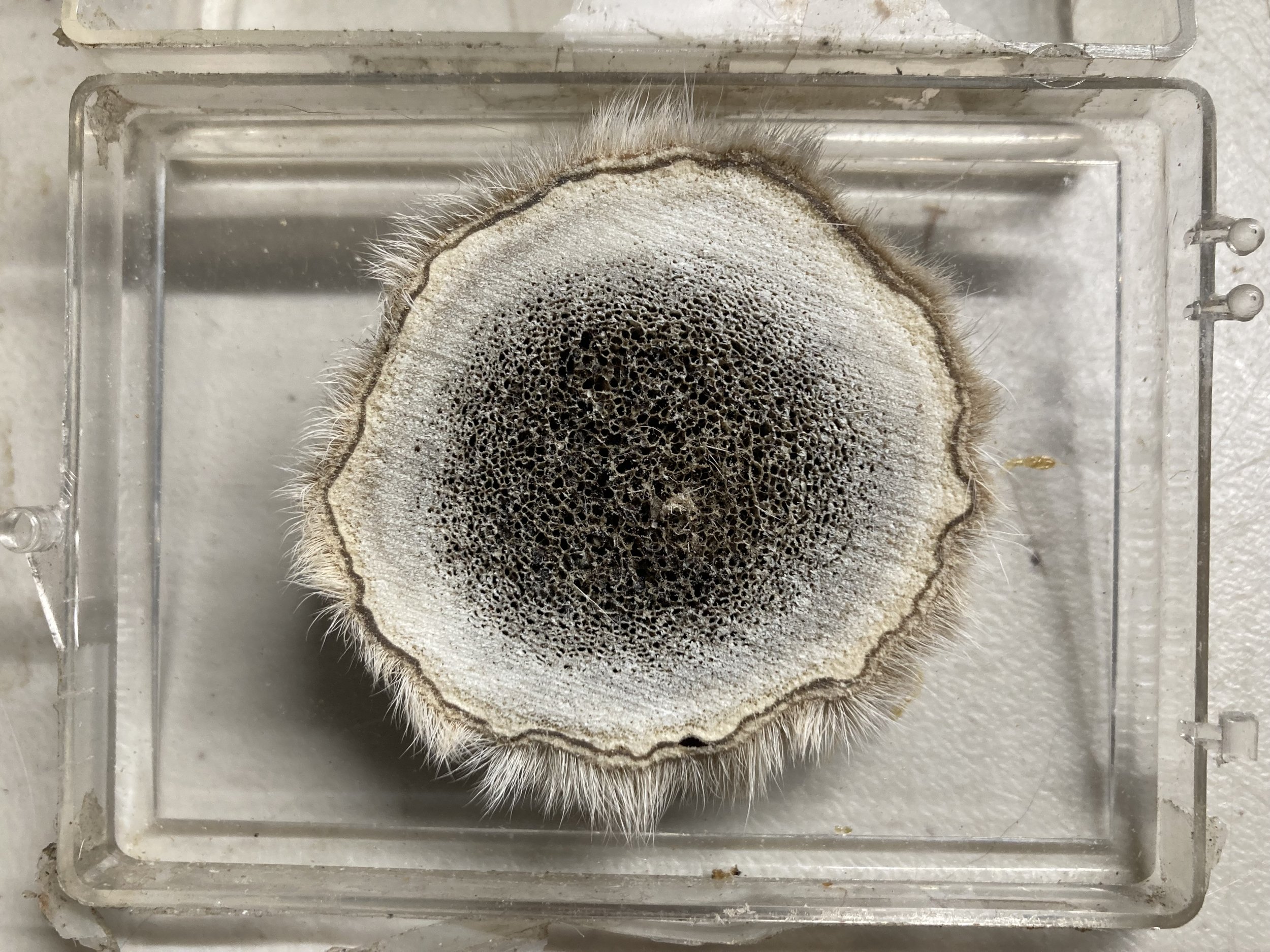

Henry also showed us a small, maybe half-inch cross-section of velvet antler in a small plastic case. It looked like something you’d see in a gem or fossil shop.

Jessica Hunt: Oh my gosh, it looks like a geode.

Henry Ahern: So that's what gets ground up and it's put into a capsule.

[mux]

As you’ll read on virtually every website that sells it, velvet antler has been used in Traditional Chinese medicine for thousands of years. In Asia, they’re sold whole, in dried slices, or as a ground powder used for making soups.

In the U.S. it’s mostly popular as a supplement.

Henry Ahern: They're good for both humans and pets.

The benefit for dogs is largely uncontroversial - and even animals in the wild will snack on antlers given the chance.

They’re generally packed with the sorts of stuff nutritionists love - proteins, peptides, antioxidants, and Omega-3 fatty acids… and there are studies that show velvet antler can help dogs with their immune systems, with arthritis, and a host of other things.

For humans, the story is a little more complicated. … because velvet antler contains a compound called Igf-1, or “Insulin-like Growth Factor”. So much so that the World Anti-Doping Agency has gone back and forth on whether velvet antler should be considered a banned substance in professional sports.

But scientists really do see promising evidence that velvet antler can be of benefit to humans. More of that in the second half of the episode.

Jessica Hunt: Do you take them?

Henry Ahern: I take them. Yep. I have for a long time, so it's good. Makes me feel good. Keeps me young.

[mux]

Taylor Quimby: I read about an MMA fighter who was banned for a year for testing positive for doping after taking velvet antler.

Jessica Hunt: no kidding!

Taylor Quimby: You’d think they wouldn’t care, I mean, come on. Shows you what I know.

So if antlers are wonder bones that grow like weeds and are packed with nutrients - Well, what are they actually doing for the deer?

Why expend all that energy growing them every year if you just lose them?

Jessica Hunt: Well, you might think they’re for fighting.

Taylor Quimby: Sure.

Jessica Hunt: Well you’d be WRONG [laughs].

Taylor Quimby: Not the first time.

Jessica Hunt: Sometimes male deer will get into a pushing match during the high-testosterone period when they breed.

[SFX]

They’ll lock antlers and occasionally get injured. But when it comes to predators deer are a flight before fight species.

So mostly, the antlers are just for show.

Taylor Quimby: So this is a classic example of sexual selection: Big healthy antlers are a sign of a big healthy animal - and the bucks or stags with the biggest rack tend to be the ones who do the mating.

Jessica Hunt: Right. But antlers might also play a role in hearing. Moose grow those huge palm or paddle-shaped antlers - and studies have indicated they might act like satellite dishes, increasing the sensitivity of their hearing.

Taylor Quimby: Oh my god, that’s so cool.

Jessica Hunt: But whatever shape they come in, antlers are cumbersome… so in the winter, males suddenly shed them - leaving a bloody hole, or pedicle, on their heads. The pedicle scabs over, and then the whole process starts again next year - with an even bigger set of antlers.

I said that wild animals love a good shed antler - and in fact, they’re a valuable source of calcium and protein in forest ecosystems.

Raccoons, porcupines, squirrels, even deer will munch on their own shed antlers.

That is, if a human doesn’t come grab them first.

Will Staats: Yeah, in a perfect world, oh, we wouldn't touch a thing, you know, but we're part of that system, you know, we're all part of the system. I'm an animal too.

Jessica Hunt: Coming up - the shed hunters! Stick around.

Taylor Quimby: You know when I want to go shed hunting I just go to Lowe’s. [pause] Get it?

Jessica Hunt: No [pause] Shed, shed, shed, shed. Oh man.

BREAK

JH: [car door shuts] My god, everything you said came true! The roads were so icy, and the logging trucks!

Will Staats: Yeah yeah, I just see that one go up, I was wondering if that one was in front of you there.

Jessica Hunt: Welcome back to Outside/In, I’m Jessica Hunt.

Taylor Quimby: I’m Taylor Quimby.

Will Staats is a former wildlife biologist who’s been hunting shed moose antlers, for about 40 years.

Will’s enthusiasm for moose antlers is off the charts. He’s got a tree out back where he piles up old ones - he calls them “junkers.” They’re jammed under tables, piled in corners. Will tells me each one is like a snowflake.

Will Staats: So these are all unique, there's a hole through this one. This one's got a unique bend to it. This one here has a point broken off where it fought with another moose. See the point right there?

Will has found so many sheds, he’s devised his own lingo for describing them.

WIll Staats: This one I call a taco antler, because it has a fold like a taco.

Now these are standalones. These antlers antlers in the corner. Yeah, I call them standalones because they stand up on their own.

This looks like a Mickey Mouse ears or something like that.

Taylor Quimby: His house sounds like the Disney World of moose antlers…Antler World!

Jessica Hunt: Is there a kettle

Will Staats: Boiling or yeah, that's deer bone soup. Oh. Yeah, I got to turn it down a little bit. Yeah, that's that's.

But, because of his career as a wildlife biologist - the antlers aren't just interesting to look at, or good for making bone broth.

Every one is a window into the life of the animal that produced it.

This moose was sick. This one was old.

Will Staats: So this moose was in poor condition… This was from likely a yearling moose.. very often, not super often, but pretty often when a moose sheds its antler, it often breaks out a piece of skull. That's a piece of skull.

[mux]

Jessica Hunt: Unlike the deer farmer from the first half of the episode, Will doesn’t just cut off his collection from captive animals. He personally found each one, and carried it out of the woods himself.

Will Staats: : It's it's a giant treasure hunt. It's a giant treasure hunt every year.

Some shed-hunters use snowmobiles or even drones to search for antlers. Will hunts on foot. He’ll cover as much as 13 to 15 miles per day…and figures he logs close to 300 miles searching every year.

Will spends so much time in the woods - he’s actually heard a bull moose lose an antler in real time.

Will Staats: : He knocked it off on a yellow birch tree. And I mean, if you Could have heard the noise he made when he hit that thing now, I don't think he did it on purpose. I think he was going down. Halladay ding dong through the woods towards that cow and bullet. He just whacked into this tree. It was a tremendous pow.

[mux]

Taylor Quimby: Ok, so I just googled the deer population in the United States, there are over 25 million deer. I know there’s way less moose, the population is dwindling. But that means we’re talking about millions upon millions of antlers being dropped onto the forest floor every year. And I’ve never freaking found one!

Jessica Hunt: Oh me either, ever. And now that I’m doing this podcast it’s driving me mad to think there are all these antlers out there and you can’t find even one.

Taylor Quimby: Right. So how does Will do it?

Will Staats: “You have to know what to look for. So you got to look for bull sign. So you've got to know that it's a bull there, not a cow, not a cow and a calf… Cause they’re going to leave lots of sign they’re gonna leave poop all over the place, and you’re going to look for feedings sign. . You're going to look for trees that they've rubbed with their antlers. They do lots of rubbing to get rid of those antlers, so you’re looking for rub trees. That is like a beacon to you. I can spot a rub tree a 100 yards away and so can any shed hunter, and you’re going there! Now it’s not necessarily the antler is going to be at the base of that. But those antlers tells you there’s a bull there. You might have to walk 5 miles behind a locked logging gate, and then start searching, and then carry 30, 40, 50 pounds of antlers on your back. But it’s worth it.

Jessica Hunt: Will loves antlers - but it’s not just a passion. It’s also a side gig.

Taylor Quimby: So he sells them?

Jessica Hunt: Yeah, some of the lower quality ones he sells as dog chews.

Taylor Quimby: Well I guess dogs don’t care.

Jessica Hunt: But veterinarians mmm, they’re mixed. They are very hard and they can break teeth if a dog really goes at it. And he also sells them to crafters, or people who want to make furniture out of them.

Taylor Quimby: Or art. People like to hang them up.

Jessica Hunt: Exactly.

Taylor Quimby: Whenever I’m up in the white mountains - all the restaurants and hotels are completely decked out with alpine decor. Like A-frames, antler lamps, antler chandeliers… antler butter knives.

Jessica Hunt: I have an antler on my mantelpiece. I’ve had it for over 25 years, and I’ve moved with it like four times…why??

Taylor Quimby: Because it’s evidence of a moose!

Jessica Hunt: It’s cool, yeah.

[clip]

The price, Will says, is determined by the color. A brown antler means it was dropped this year, and if it’s in good shape and not chewed by other animals, it fetches top dollar.

In a good year, he can make a few grand - enough to fund his yearly canoe trip.

Will Staats: Yeah, I mean, I you know, yeah, my my life is dictated by seasons, I guess you would say. I mean, you know, spring is antler hunting and then and then summer is, you know, canoe trips and canoeing and and then come into fall. It's heavy duty hunting for deer. And then all winter we track bobcats and then spring it sugaring and then back to shed hunting. So there's a circular sort of rich, you know, circular sort of pattern of living. That's that just is what I do.

[mux]

Okay. So after a break, we’re going to talk more about the science behind how deer produce so much bone in such a short period of time - and why scientists think that could be the key to treating human bone diseases.

But first, a quick deer fact speed round.

[mux transition]

A female white-tailed deer is called a….

Taylor Quimby: Doe, a deer, a female deer. [pause] A doe.

Jessica Hunt. A doe.

Taylor Quimby: You know the song!

Jessica Hunt: You confused me! All those answers.

Ok, a female caribou or moose?

Taylor Quimby: Is a cow.

Jessica Hunt: And a female red deer?

TQ: Ok, we’re really playing this, because I was there when we learned this…It is called a hind.

Jessica Hunt: And the breeding season for white-tailed deer, caribou, and moose?

Taylor Quimby: Is called the rut.

Jessica Hunt: And for red deer?

Taylor Quimby: I really like this one… it’s called “the roar.”I wish I could name one of these. If I discover an animal can I name it’s breeding season… the “fluff”…the “creep”.

Jessica Hunt: TMI…

[sfx]

Taylor Quimby: And here’s one last quiz question to see if you were paying attention earlier… I obviously had not been

Henry Ahern: Are Santas, reindeer, boys or girls?

Taylor Quimby: I think they are. I think they usually have antlers, right? So, they're probably all bucks… stags.

Jessica Hunt: Trick question. They're all female.

Henry Ahern: She’s right. The males all lose their antlers in November. They fall off in November, early December. So Santa's reindeer all have to be females because they're the only ones that have antlers left.

Jessica Hunt: All right, that's been going around on like Instagram.

[mux]

Jessica Hunt: Remember, deer listener, Outside/In is only possible because of the support of people like you. So if you’ve learned anything wild so far this episode that you’re probably going to talk to someone about - tell them where you heard it, and donate to the show at outside/in radio dot org. There’s a link in the show notes.

BREAK

Welcome back to Outside/In, I’m Jessica Hunt. Taylor, have you ever heard of the ship of Theseus?

Taylor [paraphrases]: There’s a famous philosophical paradox about an Ancient Greek hero named Theseus. Actually, it’s really about his sailing ship.

The paradox goes like this: as the ship aged, the crew replaced its old wooden planks with new ones. Eventually, every piece of the ship has been replaced - so that, even though it was well used, it looked just as good as it did the day it first set sail.

So…is it still the same ship? Or is it something new? Can something change completely, and yet still be the same?

[curious mux]

Jessica Hunt: Ok. I want you to imagine that the ship of Theseus is actually your body. Over time, you’re replacing all of your skin cells as they slough off. Same with all of the tissues that make up your organs. Even your bones are quietly, and constantly being replaced.

Old bone tissue is being reabsorbed to supply calcium to the rest of the body, and new, stronger bone tissue is being laid down - just like the planks on the ship of Theseus.

Whether or not that makes you a different person is an interesting question, but let’s forget about the paradox.

Taylor Quimby: we’re talking about antlers here…this is an antler show

I want to talk about what happens when the process gets unbalanced. Because unlike the mythical ship of Theseus, we do age. At some point, the crew can’t keep up - and our bodies start absorbing more bone than they replace.

When bones become especially weak, it’s called osteoporosis - which is Latin, for “porous bone.”

For someone with osteoporosis, their bones break easily and they grow shorter and more stooped over as their spines begin to compact.

Taylor Quimby: I’ve actually seen pictures of bone under magnification, healthy bone should look like a tight honeycomb or a dense spiderweb. With osteoporosis patients, it starts to resemble a very very holey swiss cheese…like the spiderweb is thinning, there are fewer strands. It’s pretty wild to look at.

Jessica Hunt: Right. Osteoporosis affects millions of Americans, especially women, over the age of 50. And once it gets bad, there’s no reversing the process.

But deer get osteoporosis every year. Antlers grow so fast, their bodies rob their shoulder blades and ribs for materials - calcium and protein - and while the new rack gets stronger, these other bones get weak and fragile.

But then, unlike humans, they can undo the damage. Their antlers fall off, their shoulders and ribs fill in with stronger bone mass, and the cycle begins anew.

Taylor Quimby: So what you’re telling me is these deer are basically Wolverine from the X-men. Mutant healing factor unlike any other creature on earth.

Jessica Hunt: exactly…exactly

Taylor Quimby: [pause] You don’t know actually anything about Wolverine, do you?

Jessica Hunt: I know what a wolverine is! I don’t know who Wolverine is.

[mux]

Despite all of the incredible stuff we told you about antlers in the first half of the episode - THIS is the true superpower of the Cervid family. Their ability to grow and regrow bone is unparalleled.

So for the rest of this episode, we’re going to be exploring how scientists think we might be able to deploy this superpower for humankind - and we’re starting with Dr. Brendan Lee.

Brendan Lee: And this is where good for, good fortune, actually, and chance is very important.

Dr. Lee is chair of the Department of Molecular and Human Genetics at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas.

And his research into antlers came almost by chance. He was meeting with a major supporter of the bone disease program at Baylor - who just happened to live on a ranch.

Brendan Lee: We were having a conversation, you know, about his ranch and really talked about, you know, how they manage the wildlife there and so forth, including deers. And you know, it's interesting that conversation led me to think more about deers and antlers"

It was researchers at Baylor who played a leading role in sequencing the genome of the white-tailed deer - which was made available to the public in 2017.

Dr. Lee is trying to take apart the antler process piece by piece, and stage by stage - to see how exactly the bone growth superpower actually works.

Brendan Lee: So we actually did do that resection the tip, the middle, the the the core. We actually also covered section to the covering called the Velvet

Our bones go through stages too - when we’re first born , we develop cartilage that acts almost like a sketch of where and how bone will be shaped. And then, in the center, it starts to transform into a spongy matrix - - before finally hardening, or mineralizing, into bone. Something similar happens when a broken bone repairs itself too.

Dr. Lee hopes that if we identify the right genes and pathways in deer, maybe we can accelerate bone repair and strengthening in humans.

Brendan Lee: If you think of bone formation as almost like a conveyor belt, you can accelerate different parts of the conveyor belt. But if you don't do it in a coordinated fashion, you just end up with a big traffic jam, so to speak.

Understanding the genetics of antlers might help with more than osteoporosis - it could speed things up when somebody breaks an arm or a leg, too.

But it’s not just bone growth that’s interesting. Researchers also want to know how to stop it.

Jessica Hunt: are you looking at only the genes that cause bone growth, or are you also looking at the genes that stop growth.

Brendan Lee: With antlers, for example, as you may know, in deer, they stop growing at some point and in fact, they shed. You can imagine what would happen if the antler just kept on growing and didn't stop it would it would basically overwhelm the deer. Because if you have uncontrolled growth, what would you end up with? You end up with cancer.

Taylor Quimby: This just blew my mind. I never thought about the idea..how many things do to speed up, speed up, speed up because that sounds like a really good thing. But what is what is fast growth. It is uncontrolled multiplication.

Jessica Hunt: yeah, so we want to harness that superpower, but it could be …

Taylor Quimby: it could be a super…non-power…what’s the opposite of a superpower?

Jessica Hunt: Kryptonite!

Taylor Quimby: Yes, kryptonite. Anyway….

Jessica Hunt: Anyway, that’s why people like Dr. Lee are looking at genes that grow bone fast, but also genes that put on the brakes. Because in order to protect their antlers from growing out of control, deer have basically developed cancer-suppression genes.

Tomas Landete Castillejos: Something that grows so fast is because it's producing energy. It's probably one hundred or one thousand or more times than a normal cell.

This is Tomas Landete Castillejos, a deer scientist at the University of Castilla La Mancha.

Tomas Landete Castillejos: So imagine somebody or elderly people or sportsmen having mitochondria at work like this

Dr. Landete Castillejos is specifically looking at velvet antler for its anti-cancer properties - which he says, don't have the same toxic effect in normal cells that chemotherapy has.

Tomas Landete Castillejos: We actually found that it is the tip part, not the middle part is active against a kind of cancer that's called a glioblastoma brain cancer that it's actually people who have it have a very short expectancy of life.

[mux]

This research is in its early early phase… Nothing has been tested on humans, or even lab animals. The next step is to try treating mice with velvet antler.

Turning an animals superpower into a human one can take decades, massive amounts of funding - and there’s still no guarantee.

Brendan Lee: I think that the challenge next is picking the right targets, because when we think about developing drugs or therapies, you know, you have to identify what we call lead compounds or lead targets. And so that's really the next phase.

[mux]

Henry Ahern: More volume. Why is it not playing?

After Henry Ahern of Bonnie Brae Farm did his velvet antler show and tell, he played us a video of his male deer during the breeding season.

Henry Ahern: That's the roar.

But he also took us out front, where he keeps a few dozen females.

Taylor Quimby: Ahem, hinds.

Jessica Hunt: Good job Taylor. Hinds. So, no antlers here - but these deer are especially habituated to the presence of people.

[sound of opening gate]

Henry Ahern: I'm not foolish enough to go in there with a bag of grain. Go.

Taylor Quimby: Ok. Oh my God. Hi. Oh boy. Oh boy.

The audio doesn’t really do it justice - but this is the sound of several deer slurping grain out of our bare hands.

Henry Ahern: Did you get a kiss? Lower your head like this.

Taylor Quimby: [laughs] Do you guys ever talk?

[mux]

It was pretty special for a couple of non-hunters to be able to be this close to what we generally think of as an elusive animal.

But just a couple days later, I saw a New York Times article with a picture of a scientist standing right next to a deer - like we were - but he was wearing a mask.

A new study shows that some 60% of deer in Iowa have tested positive for Covid-19 - another outlines what may be the first case of Covid-19 passed from a deer to a human.

We don’t know how they’re getting it. We don’t know if it’s making them sick. But we do know that deer could wind up being a reservoir for new mutations - spreading disease at the same time that we’re hoping they can help us to treat it.

Taylor Quimby: I was literally kissing the deer. It seems like a bad idea in retrospect. What was I thinking.

Jessica Hunt: but they were very cute..and they had gigantic eyes, and they were quiet and polite. So should we think of deer as beautiful?

Taylor Quimby: Mysterious?

Jessica Hunt: Creepy?

Taylor Quimby: Bambi?

Jessica Hunt: Sweet? Dangerous? Amazing?

Taylor Quimby: Either way…

Jessica Hunt: It’s enough to make you say… “Holy Scat!”

[mux]

Taylor Quimby: Well thank you Jessica for this very fun but also alarming story.

Jessica Hunt: It was my pleasure.

Taylor Quimby: So there are at least three things you’re going to want to see after listening to this story, and we’ve got all of them at our website and in the show notes.

Jessica Hunt: We’ve got pictures and video from my trip to see Will Staats, so lots of antler footage there - Also a video of deer creeping Taylor out at Bonnie Brae Farm.

Taylor Quimby: Ok, they're all following us… super weird!

Taylor Quimby: And we’ve also got some videos of deer rubbing off their velvet, locking horns - and even one that shows you what it looks like to amputate abnormally growing antlers during the velvet stage - which is definitely a little graphic, so be warned.

Anything else?

Jessica Hunt: Yeah, actually, I want folks to send us pictures of their own shed antlers or antler decorations! Tag us on Instagram, we’re @outsideinradio.

Taylor Quimby: Or email us at outsidein@nhpr.org.

Jessica Hunt: This episode was produced and researched by me, Jessica Hunt and Taylor Quimby

It was mixed by Taylor Quimby

Edited by Taylor Quimby and our Executive Producer, Rebecca Lavoie

Additional editing by Felix Poon.

Taylor Quimby: Special thanks to Cindy Downing and David Hewitt.

Our theme is by Breakmaster Cylinder

Additional music by Arthur Benson and Claude Signet

Outside/In is made possible because of listener support - there’s a link in the show notes to donate. This is a production of New Hampshire Public Radio.