Fortress Conservation

In the first few years after Ulysses S. Grant created the first national park in 1872, Yellowstone was so remote that hardly anybody could afford the time and cost required to see it.

But things quickly started to change. As settlements grew closer, white poachers started killing off thousands of Yellowstone’s prized elk. And growing numbers of tourists discovered that the park, advertised as untouched wilderness, was not in fact uninhabited.

Featuring Karl Jacoby, Prakash Kashwan, Rosalyn LaPier, Hadrian Cook, and Vicky Tauli-Corpuz.

Want more Outside/In? Sign up for our newsletter!

In 1877, members of the Nez Perce - just one of many tribes that lived in or moved through the region - encountered a group of white tourists while traveling on an ancestral trail. At the time, the Nez Perce were engaged in a moving war and fleeing the US Army. Fearing the tourists might disclose their location, the Nez Perce kidnapped them and took them to Montana.

This wasn’t the wilderness experience the US government had imagined when they created the park. And so, in 1886, they called on the US Army to fend off white poachers and drive away indigenous tribes. They called their new home “Fort Yellowstone,” and for thirty years, the US armed forces managed the park.

Soldiers from Fort Yellowstone, posing with captured buffalo heads after apprehending a white poacher.

Throughout the 20th century, conservationists and environmentalists have looked to protect wildlife and biodiversity through the creation of parks and other forms of exclusionary wildlife zones; zones that seek to preserve spaces devoid of human impact, or to create them, by removing or dis-empowering indigenous people who already live there. Today, some academics call this strategy by a pejorative name: fortress conservation.

But fortress conservation relies on the myth that you can separate humankind from the natural world. When forests are turned into fortresses, they require guards, gatekeepers and administrators. People who decide how fortresses can be used… and by whom. And the history of the US National Parks is filled with examples of parks created through the forcible displacement of indigenous peoples.

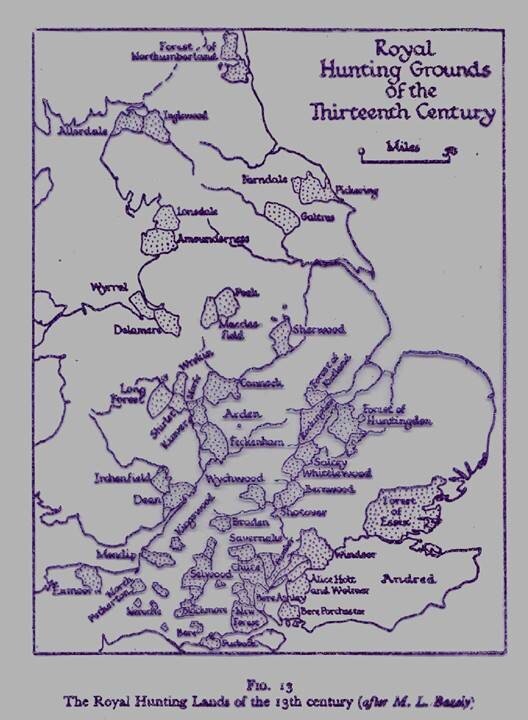

Of course, restricting access to outdoor spaces didn’t start in the 19th century. Arguably, one precursor to modern fortress conservation comes from medieval Europe. After the Norman invasion, in the 11th century, William the Conqueror put as much as a quarter of what is now England under Forest Law. Towns were depopulated to create these spaces, and hunting was outlawed, except for by the King and his men, or with his permission. The taking of lumber and other resources from these spaces was highly regulated, and poaching deer was punishable by death.

The story of Robin Hood, who lived in the Sherwood Forest with his band of Merry Men, is, in fact, the popular tale of a medieval poacher - illegally taking game and wood from a royal forest.

Today, models of fortress conservation - as popularized by 19th century American conservationists like President Theodore Roosevelt - have spread all over the globe. And similar patterns of displacement have emerged: in creating exclusive wildlife zones and national parks, countries and conservationists sometimes disenfranchise and/or displace native and poor populations.

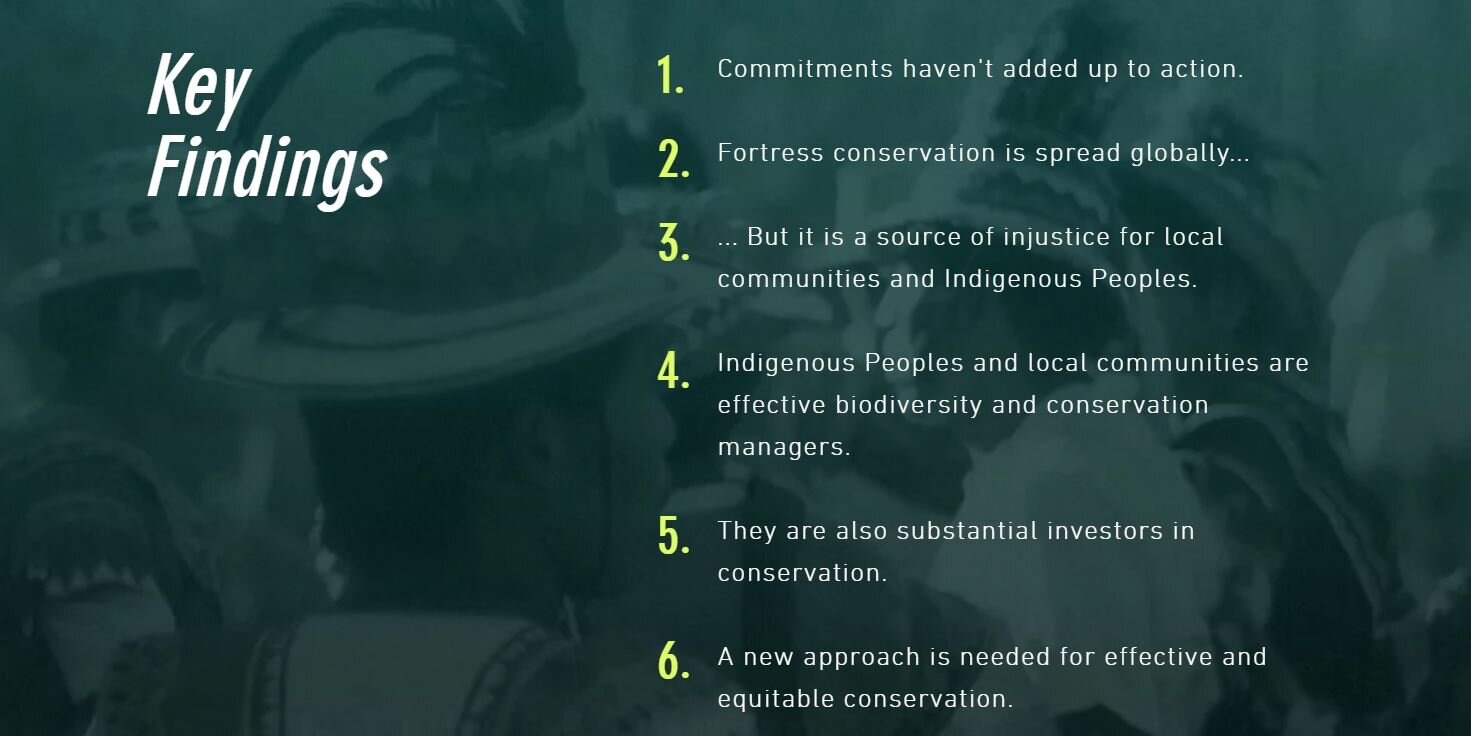

In 2018, former UN special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Vicky Tauli-Corpuz outlined the problems with fortress-style conservation, and made suggestions about how the environment movement can do better: by empowering local and Indigenous communities, who she argues are just as invested (and more efficient) when it comes to protecting the planet.

From the UN Special Rapporteur on The Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Cornered by Protected Areas.

Editor’s Note: A previous version of this podcast stated that there were oil and gas wells on 40 sites managed by the National Park Service . The actual number is 12 . There are 40 sites in total that have active wells, or are at risk of drilling. See this article for more information.

Credits

Outside/In was produced this week by Taylor Quimby with Sam Evans-Brown and Justine Paradis.

Erika Janik is our executive producer.

Our theme music is by Breakmaster Cylinder.

Additional music by Blue Dot Sessions.

If you’ve got a question for our Ask Sam hotline, give us a call! We’re always looking for rabbit holes to dive down into. Leave us a voicemail at: 1-844-GO-OTTER (844-466-8837). Don’t forget to leave a number so we can call you back.