Dispatches from the New American Shore

Elizabeth Rush. Credit Stephanie Alvarez Ewens.

When writer Elizabeth Rush visited neighborhoods already transformed by rising seas, she noticed that many people did not use terms like “climate change.” They still talked about it – it’s just that they talked about it in terms of their own experiences: the dolphins, swimming in tidal creeks further inland than ever before… how the last big flood wasn’t gradual, but fast and sudden.

Rampikes and bayou around the Isle de Jean Charles. Credit Elizabeth Rush.

In this episode, we’re looking for new ways to discuss climate change with Elizabeth Rush, author of Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore. While some books about climate change are heavy on politics and UN reports, Rising is not that. Instead, Elizabeth focuses on the people, species, and communities on the leading edge of sea level rise, from New York to California, Louisiana and even to the mountains of Oregon.

“A good friend of mine… was like, ‘This is the first climate book I've also read that has zero quotes from politicians.’ That wasn't purposeful, but I looked back and was sort of proud of that,” Elizabeth said.

Credits

Hosted by Justine Paradis and Felix Poon

Reported, produced, and mixed by Justine Paradis

Edited by Rebecca Lavoie

Additional editing: Taylor Quimby, Felix Poon, and Jessica Hunt

Executive producer: Rebecca Lavoie

Theme: Breakmaster Cylinder

Additional music by Chris Zabriskie and Blue Dot Sessions

If you’ve got a question for the Outside/In[box] hotline, give us a call! We’re always looking for rabbit holes to dive down into. Leave us a voicemail at: 1-844-GO-OTTER (844-466-8837). Don’t forget to leave a number so we can call you back.

Audio Transcript

Note: Episodes of Outside/In are made as pieces of audio, and some context and nuance may be lost on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors.

Justine Paradis: This is Outside/In, a show about the natural world and how we use it. I’m Justine Paradis.

Felix Poon: And I’m Felix Poon.

Justine Paradis: Felix, you know that feeling when you learn that a thing you’re observing – that there’s actually a word for it? Like, you didn’t know that there WAS a word for a particular phenomenon… but it does have a name.

Felix Poon: Yeah a word that comes to my mind, I’ve been learning some Portuguese and one Portuguese word being ‘saudade.’

Justine Paradis: I don’t know that one.

Felix Poon: It's kind of like nostalgia, or longing for these old memories… it’s both good and bad. Bittersweet, maybe is the best equivalent in English?

Justine Paradis: Interesting one. I often find that when I learn someone else, and many many people, have described this phenomenon that I’m observing, it’s like, suddenly I get to experience it in a new way. And I feel recognized, somehow. And the way writer Elizabeth Rush puts it is – it’s almost like something is unlocked, and the word is like a key.

Elizabeth Rush: So as I started to spend a lot of time in coastal wetlands, I started to notice this really strange phenomenon: that in every single wetlands ecosystem that I was visiting, many of the hardwood trees were dead.

MUX: Maldoc, Blue Dot Sessions

Justine Paradis: The word for the phenomenon Elizabeth is describing is “rampike” - r-a-m-p-i-k-e. A rampike is a standing dead tree, undone by natural forces – in this case, death by salt water, as it rises.

Elizabeth Rush: And you see them. I promise you, go to a tidal wetland anywhere and you will see rampikes.

Justine Paradis: These standing dead trees, inundated by salt water, are to Elizabeth a visual marker of climate change – a way to actually SEE it. But that’s not all they are.

Elizabeth Rush: There is a deeper way in which I want the rampikes to function, which has to do with, I think, a big question that is at the heart of this book, which [00:31:00] is sort of once you're vulnerable, what do you do with that sense of vulnerability?

Justine Paradis: Rampikes are a starting image of Elizabeth’s book, Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore.

Elizabeth Rush: And at a human level, it really circles around that question of: do you stay or do you go? How do you stay in a place that's defined you even as it’s sort of changing irrevocably right beneath your feet? And how do you know when it's time to leave?

Justine Paradis: Rising is the subject of today’s episode AND the latest Outside/In Book Club pick.

Felix Poon: So Justine, If I’m a listener, and I haven’t read this book… should I bail right now?

Justine Paradis: NO! You do NOT have to have read the book to enjoy this episode.

Felix Poon: Okay that’s good.

Justine Paradis: Yeah, actually, a lot of books about climate change can be kinda wonky, heavy on the policy or on politics… but Elizabeth’s book is NOT that.

Elizabeth Rush: A good friend of mine who's a journalist in Washington, D.C., was like, ‘This is the first climate book I've also read that has zero quotes from politicians.’

Justine Paradis: [laughs]

Elizabeth Rush: That wasn't purposeful, but I looked back and was sort of proud of that.

Felix Poon: Many of the people Elizabeth talked to did not use terms like climate change or sea level rise…. They still talked about sea level rise — it’s just, they talked about it in terms of like, the soil, and how it smells different now.

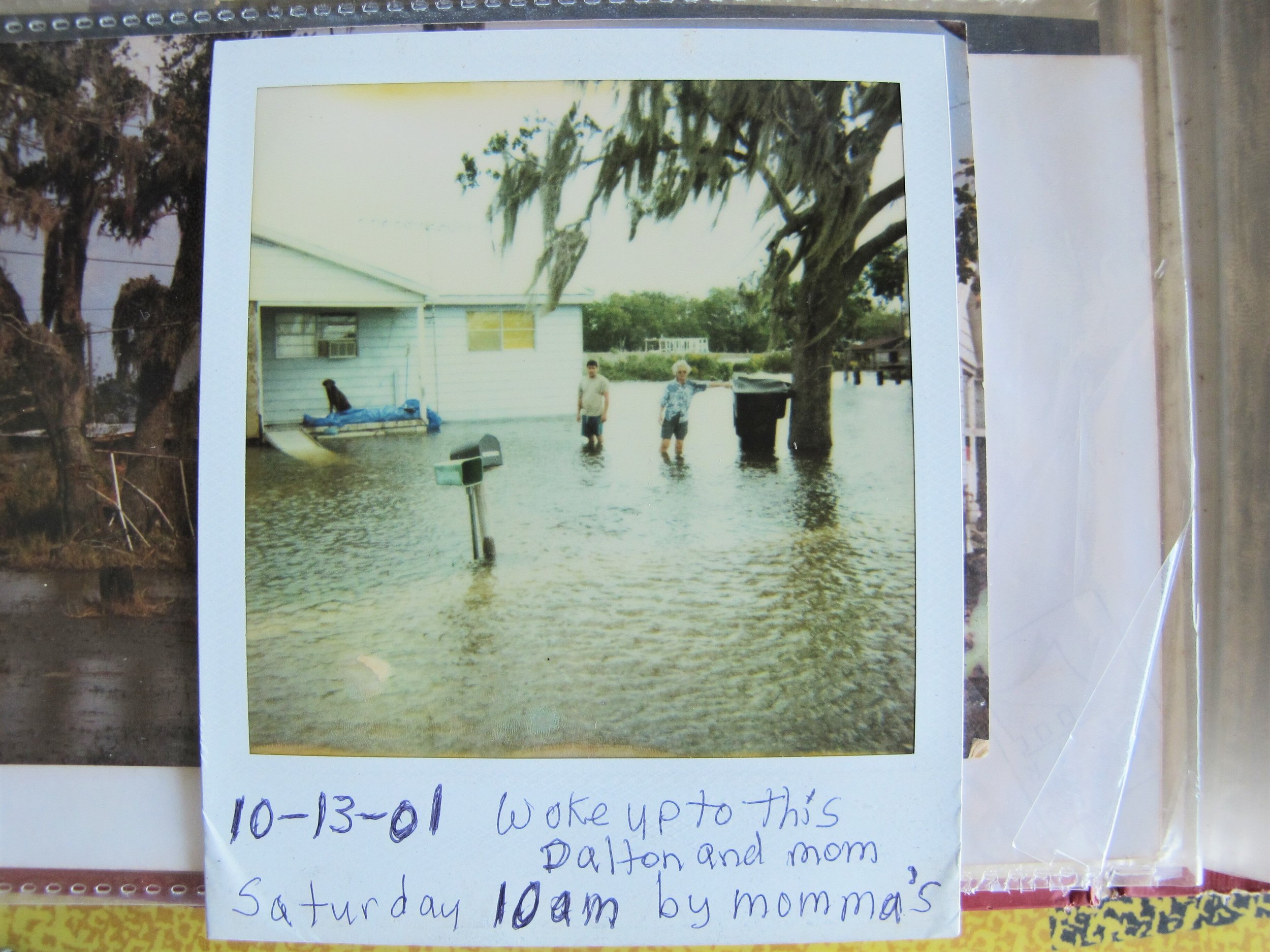

Justine Paradis: The dolphins, sighted further inland than ever before, swimming up deepening tidal creeks. How the last big flood wasn’t gradual – but fast and sudden.

Elizabeth Rush: Really intimate stories about what a person loses in a storm, about really specific objects and memories that are tied up in home places… and what they decide to do with the knowledge that not only are they vulnerable, but that there's a shared vulnerability amongst them and usually their neighbors.

Felix Poon: But reporting on communities that are vulnerable to sea level rise – both human and wildlife – is a complex thing.

Elizabeth Rush: I felt like if I was spending time in these communities and asking residents to share with me… that I had to make myself vulnerable too.

Justine Paradis: So, today on Outside/In, a conversation with writer Elizabeth Rush, on the people and species on the leading edge of sea level rise… and what it was like to report on that for her book Rising.

Elizabeth Rush: “It’s about rising sea levels, but it’s also about rising into awareness and rising into power.”

MUX FADE

Justine Paradis: Tidal marshes are places that for a lot of people are not TOP of mind. That was true, for Elizabeth, at least. But eventually, the tidal marsh became central to her reporting.

Felix Poon: Here’s Elizabeth, reading from Rising.

MUX IN: Clouds at the Gap, Zither, Blue Dot Sessions

“To most, a wetland is just a mess of grass. The sulfuric scent of decomposition, miasmas and mud. But I'm beginning to see them as divining rods, signaling where there will be more water in the future, and even more importantly, that the future is, in many cases, already here.”

Justine Paradis: Why is the tidal marsh so important to think about?

Elizabeth Rush: Oh, they're important for a million reasons. I should also say that when I started writing this book, I quickly figured out that I was going to have to spend a lot [00:19:30] of time in marshes, and my first response was like snooze! *** Who likes the Marsh. And the more I worked on it, the more excited I got about marshes because I started to recognize just what a dynamic ecosystem they are.

Justine Paradis: Tidal marshes are dynamic – that is, constantly changing. It’s right there in the name – they’re tidal! And – the roots of the grasses that grow there help protect the coast, by cushioning the force of waves like a shock absorber. Plus, they’re carbon sinks. Marsh grasses and their roots sequester carbon in the soil.

MUX OUT: Clouds at the Gap, Zither, Blue Dot Sessions

Justine Paradis: So, Felix. You know how, when you read a book that you like and you get really excited about it, at least for me – there’s often one specific factoid or story that I tell just EVERYONE about in every conversation.

Felix Poon: Yeah! Totally. I do that too. What’s the part of Rising you’re really excited about?

Justine Paradis: Well I guess ‘excited’ might be the wrong word but the thing that blew my mind was when more and more ocean water floods a tidal marsh for more and more time… in some cases, the marsh literally ROTS.

MUX begin: Headlights, Blue Dot Sessions

The underground roots begin to decompose, and the ground starts to collapse. The marsh even starts to smell different – a “musky, almost strawberry scent of decomposition,” as Elizabeth puts it (p48).

Elizabeth Rush: Some of the marsh grasses are gonna be a little bit more adept to living with higher levels of saline, others are less so. And so in places where you see marsh grasses that don't have that built-in adaptability spending more time, more hours underwater every day they rot. They, they die, and they as marsh grasses rot, they release methane into the atmosphere, which is actually a more powerful greenhouse gas than CO2.

Justine Paradis: So… not only is the marsh dying and the coast is losing that protective buffer, but it’s also losing its capacity for carbon storage.

Felix Poon: Yeah, it’s like the function of the marsh.. flips, it used to be something that sequesters carbon, but now it’s something that emits greenhouse gases.

Justine Paradis: mmmm. Yeah.

MUX FADE

Justine Paradis: Elizabeth features eight different communities dealing with these changes. Most are coastal, which makes sense - Miami, Florida, Berkely, California, Staten Island, New York …

Felix Poon: But there’s one place she reports on that’s a little surprising.

Justine Paradis: There's one point in the story where you journey very far from the shore to the Cascades in Oregon. This is a book about sea level rise. Why are you in Oregon? In the mountains?

Elizabeth Rush: I'm in the mountains at a writing residency to try to write this book, Rising, and even there, where I think I won't be immediately haunted by the impacts that rising sea levels are having on wetlands communities… and come to find out that… many of the breeding birds who find their way to this mountain to make their babies get there by migrating through tidal wetlands. And so as the tidal wetlands disappear, fewer and fewer of these birds are making it. So, you know. It becomes clearer that when we talk about the impact of rising sea levels on coastal communities, the aftershocks of that reverberate all throughout the country, even eight thousand feet above sea level.

[MUX]

Felix Poon: Yeah, it’s kind of like how Elizabeth discusses in the book that a lot of coastal areas, they’re no longer getting resupplied with sediment because we’ve dammed off a lot of rivers. It kind of really illustrated for me that a problem isn’t just isolated in one place. It’s all interconnected, really.

Justine Paradis: Yeah. Ecosystems are not closed containers at all.

As Elizabeth was describing this experience in the forest in Oregon, I started to visualize these tidal marshes are almost all this one ecosystem, all connected in the US and the world… imagine, let’s say you or I were going on a road trip and you’re looking for spots to refuel or to get snacks or to go to the bathroom – you look for a certain kind of place that exists all along your route that can help you do that. And I feel like if you’re a migratory bird, that’s what a tidal marsh is.

MUX: Dell Mare, Blue Dot Sessions

Felix Poon: They’re little fueling pit stops for the birds?

Justine Paradis. Yeah. Here’s Elizabeth, reading from Rising again.

I think about the places these birds pass through on their way here. Of the disintegrating cypress swamps the Rufous hummingbirds fly from. Of the willow groves that Swainson's thrushes have long thought out in San Francisco's South Bay. Of the drowning bayous the ospreys pause in before crossing the Gulf. The birds are all nomads, at home in movement. But what happens when points along their paths begin to disappear? What disorientation will settle upon all of us then?

Justine Paradis: After a break, Outside/In journeys with Elizabeth Rush from the mountains to the bayou. We’ll be right back.

MUX FADE

Justine Paradis: Outside/In is a member and listener supported podcast. We rely on listeners, like you, to take the leap to donate to support the show – if you’re able. It’s quick and easy – just go to outsideinradio.org and click DONATE. And thank you – so much.

// BREAK //

Justine Paradis: This is Outside/In. I’m Justine Paradis, here with Felix Poon. So, let’s talk about one of the communities Elizabeth Rush spent time for her book Rising. The Isle de Jean Charles, in Louisiana.

MUX in

Elizabeth Rush: Oh, the island. First and foremost, I just want to say it's a really stunning place.

Justine Paradis: It’s about an hour and a half from New Orleans – first through these raised highways through the marsh.

Elizabeth Rush: …you like kind of cruise through at eye height, you know, swamp oak and cypress

Justine Paradis: And then – the highway drops down to wetlands – and sea level. And then it jags out – onto open water.

Elizabeth Rush: And then you hang a left and you're on the island.

And it’s sort of this spine of land surrounded by open water. It's a single road. Out at the end is a marina that kind of doubles as the local hangout place, where everyone gathers and like boils crawdads and drinks beer. And then most of the homes out there kind of look like trailers up on like 20 foot high stilts. You just you can jump in your boat, off the bat, in your backyard and just be out in the water. 50 years ago, all that was wetland!

Justine Paradis: 50 years ago, the Isle de Jean Charles was 10 times bigger. Elizabeth said about half the swamp trees she saw around the island are now rampikes – standing dead.

Felix Poon: And for decades, the big gnarly question has been – how long can people keep living there?

Elizabeth Rush: The folks who live out there tend to be members of the Biloxi Chinamacha Choctaw tribe, though the island isn't recognized as reservation land because of the intermarriage of folks. So it's easier to get sort of that tribal recognition if it were just Choctaw or if it was just Chitamacha. But all of these different tribes convened on this really vulnerable land about two hundred years ago, as each of them was fleeing similar kinds of but different moments of colonial violence… and they convene on this place in part because no one really wants this land. And in that sense, it acts as a kind of invisibility cloak…

Justine Paradis: As the island has shrunk and shrunk in size, a lot of people have left. Those that have stayed – are quite vulnerable to storms, especially hurricanes.

MUX IN : Sleeper stems, Blue Dot Sessions

Elizabeth got to know two people in particular living on the island at the time– Chris Brunet and Edison Dardar. Both really love the island… and they’ve responded differently to the changes happening all around them – especially the idea of collective relocation, also known as managed retreat. Since 2001 , much of the tribe and their leader, Albert Naquin, they’ve been organizing to resettle together.

Elizabeth Rush: Chris… is choosing to participate in relocation. And Edison says, ‘you know, I really want nothing to do with it.’ I remember him saying to me: ‘you know, what am I going to do if you move me inland, I'm just going to sit on my butt and watch TV and grow old fast.’ Edison is like in his seventies. He throws the cast net in his backyard every day. He gets shrimp out of the bayou. He lives out there and it is who he is, and he's, you know, and I don't think he's wrong to say that he would probably die sooner if you moved inland, although he might die on the island in a storm, you never know, so. But he's making this choice to stay on the island, and Chris is making a choice to be part of the relocation, and I think the chapter tries to give equal space to both of them, because I think they're both really reasonable responses.

MUX OUT

Justine Paradis: The Isle de Jean Charles is one of those places which, kind of like certain coastal communities in Alaska or the Polynesian islands, is experiencing climate change directly already. And so, it is featured in a million documentaries. So, people living in those communities – a lot of them have had a lot of encounters with journalists and media. Sometimes… those encounters… are not great.

And this brings up another difference between Chris and Edison that for me, really opens this can of worms around how do you ethically report on a vulnerable community?

As for Chris – Elizabeth witnesses him being pretty open to speaking to journalists.

Felix Poon : Yeah like once while she’s interviewing him, another group of reporters comes through to film him. And he’s like, ‘Oh I forgot about them, I think they’re from National Geographic??’

Justine Paradis: Yeah, ‘I forget where they’re from, these famous’… yeah. But Edison – the first time she goes to his house, there’s a handmade sign out front that says “ISLAND is NOT FOR SALE. IF YOU don’t like THE ISLAND STAY OFF” (p37).

Elizabeth Rush: I think it has to do with a lot of different things. Many journalists are working on really tight deadlines, and so they don't have a lot of time to commit to a place when they're doing their stories, and that's no fault of their own. That's just sort of like the 24-hour news cycle. And so they kind of like parachute into a community, gather up the stories and leave. And the longer I worked on sea level rise, the more it started to feel to me that that kind of reporting… mimics a little bit of what's happening in the extractive industries that have gotten us into the climate crisis. It's sort of like, OK, you take out the ore and whatever wealth it can generate leaves the community and the community is left sort of hollowed out by that process of extraction…

MUX IN: Flatlands, Blue Dot Sessions

Like, ‘I told you my story and like, what do I get from this deal?’ And I think that there's also a little bit of a false promise like, ‘Oh, if you speak with me, things are going to change fundamentally as a result of this conversation.’

And that's not necessarily true, right?

Justine Paradis: Elizabeth eventually does develop a close relationship with Chris, in particular – I get the impression that they’re still pretty good friends. And Edison did end up speaking with Elizabeth too. And so I really wanted to ask her: how did she gain that trust? And her main response was –

Elizabeth Rush: Whenever I asked to go report a story if I put together a budget for that reporting, I always asked for time.

Justine Paradis: Time.

Elizabeth Rush: Put me up in a cheap Airbnb, let me camp, let me have months to be in a community.

Justine Paradis: The book actually took eight years to write, and in the case of the Isle de Jean Charles, Elizabeth took two extended research trips there.

Felix Poon: And another thing Elizabeth does – is she opens every chapter with testimony, almost in essay form. Each one is authored by a resident of the places she’s reporting on. Chris is one of them.

Justine Paradis: Also, Elizabeth also wrote the book in the first person - she uses the word “I”a lot – which is maybe uncommon in straight-up journalism. And she shares a few details of her own life at times – a broken off engagement, leaving behind an apartment and a life and one possible future (p27).

Elizabeth Rush: I felt like if I was spending time in these communities and asking residents to share with me what is arguably, like, the most difficult knot at the center of their lives, asking for them to recall past traumas, that I had to make myself vulnerable too. Like it had to be a conversation, it wasn't fair for it to just be me showing up with a microphone and being like, ‘well, tell me about Hurricane Katrina.’

Justine Paradis: Yeah, like, what's the worst thing that's ever happened to you?

Elizabeth Rush: Exactly. Like, that's a nonstarter. And it's also a nonstarter to go in there and be like, ‘Well, we've moved past three hundred parts per million, and so this is what's happening in this community.’ I also don't need to be an expert on my podium telling them, convincing them that climate change is real when they know, like they know they're flooding worse and worse… So I think that, you know, it's in the book out of that necessity, out of that like human decency… and then it's also in there for a second reason, which is, I think readers are a little bit voyeuristic.

Justine Paradis: [laughs]

Elizabeth Rush: At least I'm a voyeuristic reader. I love learning about what my favorite authors have in their kitchen cabinets… or everyday struggles or big struggles that ground their lives…

Justine Paradis: It's such a real answer. Like, people are gossipy, that we love, we're all voyeurs. I am!

Elizabeth Rush: Totally! Like, I tell my writing students that and they kind of look at me like, ‘Oh, aren't we better than that?’ I'm like, ‘Are we? Not really.’

MUX: Beast on the Soil, Blue Dot Sessions

Justine Paradis: Our conversation with Elizabeth Rush continues – after a break.

////// BREAK II /////

Justine Paradis: This is Outside/In. I’m Justine Paradis.

Felix Poon: And I’m Felix Poon.

Justine Paradis: And we’re going to pick it up here – with a little non-sequitur. Because… you need to know that a book about sea level rise… can be funny.

Felix Poon: Can it?!

Justine Paradis: [laughs] Well!

Felix Poon: Okay, let’s try.

Justine Paradis: So, this comes from a moment when Elizabeth is in this forest in the Cascades in Oregon, hanging out with a bunch of scientists who are studying bird migration and breeding – and Elizabeth was shadowing them, as they tromp deep into the woods to record their calls.

Elizabeth Rush: And it was a place where there was a lot of big old growth and Doug firs and also a lot of stumps, you know, signs that a century ago, the biggest trees were removed as part of that uptick in lumber and extraction that happened in the Pacific Northwest. So we're sitting there and –

MUX: Introduction to Beetles, Blue Dot Sessions

– an owl swoops in and just like perches on this branch really close by. And then another one comes in and joins it. Spotted owls are endangered species. And they're also the species that was used to create the injunction against the felling of old growth in the Pacific Northwest.

ARCHIVAL AUDIO: “The only reason why the environmentalists are using the owl is just to work on the emotions of the people. It’s all the logs, it’s the trees that they’re after.”

And so in the world of, like, environmentalists, spotted owls are like a holy grail. And so the guy that I'm with, we're both like, ‘I think those are spotted owls. Oh my god.’ And you know, we like, silently sit there for an hour and I feel like I'm having this moment of interspecies communication, like I'm looking into its deep black obsidian eyes and it's looking back at me and I just feel so special.

And later, back at headquarters, I go to the guy who's the head of the spotted owl study, and I'm like… ‘it was so amazing, they were so close. I can't believe it.’ And he looked at me and he's like, ‘You want to know why they do that?’ And I was like, ‘Why?’ And he was like, ‘Oh, because they think that you're going to pull a bait mouse out of your backpack.’

Justine Paradis: [laughs]

Elizabeth Rush: and my like my. My dream is shattered in that moment. It just… it's become so accustomed to being observed by humans as part of these ongoing studies that are used to stop, you know, to maintain old growth… that it knows that when we come around, it can expect a special snack.

MUX SWELL AND FADE

Felix Poon: I kinda feel like this is maybe less funny than it was sad..

Justine Paradis: Well, it’s both, really. I mean it’s the sixth extinction, things are weird.

Felix Poon: Yeah.

Justine Paradis: But again there’s this theme inside it -- this theme of journalists and scientists gathering stories of vulnerability to support a larger narrative. And in this case, that story is the plight of the spotted owl, which was employed with some success – but it's still a little uncomfortable, right?

Felix Poon: There’s something about, I think, as a scientist trying to objectively observe something, you think you’re removed from it? But you’re actually not. You’re poking and prodding while you're observing… and that… there’s no way to escape that interconnection.

Justine Paradis: Yeah, the scientist tries to be sort of this objective eye… but here we’re seeing this species is changed BY that process of being observed.

Felix Poon: Exactly.

// MUSIC SWELL – BEAT //

Felix Poon: One thing about some species is there's a limit to how far they can migrate. Like if your habitat is a mountain, eventually you can’t go any higher.

Justine Paradis: Yeah. Some species, and communities, are very limited in terms of the capacity to move – while others are innately more flexible.

Felix Poon: That brings us back to the second grounding image of the book – the rhizome.

MUX IN: Out of the Skies, Into the Earth – Chris Zabriskie

Elizabeth Rush: Rhizomes are similar to roots in that they kind of drill into the ground and hold and support and absorb nutrients for a lot of these tidal wetlands, marsh grass species. But where they differ from root systems is that they're also able to send out lateral shoots that then turn into new plants. And so as an area becomes more frequently inundated… rhizomes are able to go in search of higher, drier land that might be more suitable. So they're really kind of this neat interconnected web that drives inland migration in marshes.

Justine Paradis: So, rhizomes become this metaphor for human communities that are doing the same thing.

MUX FADE

Felix Poon: One of these communities is Oakwood Beach, on Staten Island – one of the boroughs of New York. It’s pretty suburban for New York – historically very Italian American, with a reputation of being kind of an insular place.

#rJP: Elizabeth worked as a professor at the College of Staten Island for years, and she told us she’d often ride her bike over to the neighborhood after teaching.

Elizabeth Rush: It was a community that was very right-leaning, a little bit climate change denying, working class, and low-lying, and they were decimated by Hurricane Sandy.

Staten Island Residents band together after Sandy

Voice 1: Imagine going in your house an everything in there has to be thrown out.

Voice 2: We’ve heard the stories about bodies being pulled out, I myself saw them pulling out some bodies as we were doing relief efforts, and it’s tough emotionally...

Elizabeth Rush: And what surprised me was that in the wake of the storm, many residents started to band together and publicly ask that the state purchase and demolish their homes.

MUX IN: Base Camp, Blue Dot Sessions

Elizabeth Rush: They said they no longer felt safe living there. And the longer I sort of spent dwelling in the stories rising up from Oakwood Beach, the more I started to suspect that there was something that these residents knew that the rest of us who are not quite so vulnerable to climate change did not. Because I didn't understand how it was that they were asking for this, really, what's considered like a really radical climate change adaptation strategy… managed retreat, is what it's formally called.

Felix Poon: Yeah, I feel like I’ve not ever heard the language of “managed retreat” in everyday conversation.

Justine Paradis: Yeah, it’s kind of a policy word, for sure.

Felix Poon: Yeah. But I mean, it’s definitely another example of people not using the words and terminology of climate change. They’re recognizing and experiencing it firsthand, but like, they’re thinking of it more as like, ‘I gotta get out of here in a way that feels good to me,’ rather than ‘we’re doing managed retreat!’

Justine Paradis: This kind of brings us back to this language thing that we started with. Like this idea that if you are able to name something it kind of allows you to experience it more deeply. But it's almost like the reverse here. Like, if Elizabeth had kind of forced the issue here and said, ‘no, it’s definitely climate change,’ it’d be probably an example of language getting in the way of an interaction.

Felix Poon: Yeah, it’s like, a lot of terms like ‘climate change’ have cultural baggage that people can get really stuck on, and then your message just gets lost in that.

Justine Paradis: Yeah and maybe your relationship too.

Elizabeth Rush: And I think to figure out why they wanted to retreat, you kind of have to dig into the community's past and you start to see that a hundred years ago, it was all wetlands out there. And in more recent decades, you know, they flooded frequently and they're often sort of at the bottom of the city's repair list or to-do list.

Justine Paradis: I think there’s a narrative around why would anyone ever choose to live in a place that’s so vulnerable to flooding?

Felix Poon: Right.

Justine Paradis: And this is where more structural elements come in – actually, a HUGE amount of the New York metropolitan area was once wetland. About 90% actually has been backfilled and built on (p117). So, you know, a wetland acts as a “giant sponge,” as a geologist Elizabeth spoke to put it… but now a lot of it is paved or houses are built on it or whatever… and this geologist also plotted it out for Staten Island and found that: “Over half of the people who died in the storm were standing atop land that was once a tidal marsh.”

MUX OUT

And he said – a lot of these houses should just never have been built.

Elizabeth Rush: So when Hurricane Sandy came around, they read the writing on the wall. They're like: everyone's going to get money before us. Like we will be tasked with living in FEMA housing for years or in our homes with mold creeping up the walls and parts of the roof pulled off. And they just didn't want that.

Justine Paradis: And I think a major part of why this seemed to work so well – is how truly bottom-up this organizing was. Like the drive for the buyout was coming from the community, from the people living there.

Elizabeth Rush: And so someone from within the community heard about the possibility of managed retreat. And he started to advocate for managed retreat, and he understood that this was a story, an idea that had to enter into discussions sort of in a horizontal way.

So he organized these different buyout committees, and they went door to door and started educating residents on what managed retreat might mean, that you would actually get pre-storm value for your home, that the land would be held in open space in perpetuity, that a developer wasn't going to come in and and throw up a high rise condo, which was surprisingly interesting to a lot of folks.

They were like, ‘Oh no, if you're going to, if you're going to put in luxury housing here, I will rot on this piece of land. I don't want to be part of whatever would sort of make me have to give up my community so that someone wealthier could end up living there. Absolutely not.’

Justine Paradis: Even though it might be really sad for them still - you might be leaving behind the garden you started – the street where you grew up – maybe your grandparents built the porch, whatever! All these intimate details that make your life, you’re still having to leave that behind even if that’s what you want.

Felix Poon: So, these people sound pretty empowered. They’re like aware of the politics and the money involved here.

Justine Paradis: And… in the end, the organizing worked. The buy-out program ended up adding up to almost $300 million, mostly on Long Island and Staten Island.

Elizabeth Rush: and the governor eventually agreed and purchased and demolished 600 homes on the eastern shore of Staten Island, and I think th e thing that really, like, still jazzes me about the whole thing to this day is that. The city offered a five percent bonus on closing, and so 80 percent of people who participated in the buyout still live on Staten Island, they still see each other. They still go to the same grocers and butchers. What's changed is their real, immediate vulnerability to flooding.

Justine Paradis: At one point, Elizabeth writes, “I am done dreaming the earth undrowned. It is no longer a useful skill”. And I think part of the reason that the Staten Island example is so profound and feels kind of hopeful, for me, and the reason the rhizome metaphor is so apt here, because hree is this interconnected web of people. They’re moving together, and from the sound of it – the community is in large part, intact. Away from the place it once existed but the community still exists. So it sort of shows the potential of this moment, can we be more flexible and make room for this movement, in a way that is fair to human beings and to non-humans as well?

Felix Poon: Yeah I think it is a pretty apt metaphor. So, yeah maybe in some cases we can move, in an organized equitable way. But sometimes maybe there are structural barriers to that. For example I wonder would communities of color have been funded and supported the same way the Staten Island community was?

Justine Paradis: There is some data that says that communities are being treated differently but making direct comparisons I think probably has it’s limits. But I will say: I read this study which looked at the ABILITY to organize as ITSELF a quality of resilience – like that sense of empowerment, you mentioned – that’s informed by the history of activism in your neighborhood, urban infrastructure, and how close you are with your neighbors – physically and socially close… all that impacts a community’s ability to adapt and move like rhizomes.

MUX IN: What True Self Feels Bogus, Let’s Watch Jason X – Chris Zabriskie

Justine Paradis: To finish, let’s go to the beginning. Rising opens with two epigraphs. And one is a quote from the Penobscot scholar, John Bear Mitchell. He said, in part:

“Within a single human existence things are disappearing from the earth, never to be seen again. In Passamaquoddy [Maine] our sacred petroglyphs – those carvings in rock that were put there thousands of years ago – are now being put under water by the rising seas… These losses have been slow and multigenerational. We have narrowed our spiritual palettes and our physical palettes to take what we have. But the stories, the old stories that still contain a lot of these elements, hold on to the traditional. For example, our ceremonies and language still include the caribou, even though they don’t live here anymore. Similarly, we know the petroglyphs still exist, but now they’re underwater. The change is in how we acknowledge them.”

The other epigraph is from the French philosopher, Simone Weil. “Attention is prayer.”

Elizabeth Rush: I think that one of the reasons why we have such a hard time addressing climate change has to do with the fact that we're still kind of searching for the language to talk about it, to make its impact felt... And I also think that the stories we tell can also help guide us towards different futures, like we've gotten really caught up in apocalyptic storytelling around climate change, and in many ways, I think that kind of storytelling robs us from the possibility of being transformed and not only for the worse. … not just a disaster multiplier, but an opportunity multiplier. There will still be incredible loss ahead of us. I am not at all suggesting there won't be, but I think… I think the stories that we tell have the power and potential to shape the future that we want to inhabit.

And so the search for language… repeatedly carries me back to people who know more about navigating tremendous transformation, environmental transformation than the average Joe Schmo. So I think that's kind of how both of those get to be in the book, as sort of, the bell that’s struck at the beginning of the exercise.

Justine Paradis: Yeah. Thank you so much for being on the show.

Elizabeth Rush: My pleasure, thank you. This has been a really wonderful conversation. Thank you for taking so much time with my work. I really appreciate it.

// CREDITS:

Justine Paradis: That was Elizabeth Rush, author of Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore. She’s working on a new book on motherhood and Antarctica’s diminishing glaciers.

This episode was produced ,written and mixed by me, Justine Paradis, with help from Felix Poon. Editing by Rebecca Lavoie, with help from Felix Poon, Taylor Quimby, and Jessica Hunt. Our executive producer is Rebecca Lavoie.

Music in this episode came from Chris Zabriskie and Blue Dot Sessions.

Our theme is by Breakmaster Cylinder.

This is a member and listener supported podcast – if you listen to the show and are able to donate to help us keep making it – please visit outsideinradio.org and click donate.

Outside/In is a production of NHPR.