As American as hard apple cider: an immigrant food story

Forget about beer, or even water; it was hard apple cider that was THE drink of choice in colonial America. Even kids drank it! And since it’s made from apples – the “all-American” fruit – what could be more American than cider?

But apples aren’t native to America. They’re originally from Kazakhstan.

Apple trees outside Almaty, Kazakhstan (Photo by Daset S, Flickr)

In this episode we look at the immigration story of Malus domestica, the domesticated apple, from its roots in the wild forests of Central Asia, to its current status as an American icon. And we look at how apples and cider were used in some of America’s biggest migrations – from Indigenous tribes who first brought apples west across the continent, to the new immigrants who are using hard cider to bridge cultures and find belonging.

Featuring Soham Bhatt and Susan Sleeper-Smith.

Special thanks to everyone Felix spoke to at the Cider Days Festival, including Judith Maloney, Carol Hillman, Ben Clark, Ben Watson, Charlie Olchowski, William Grote, and Bob Sabolefski.

Editor’s Note: This episode first aired in February of 2022.

The Erasure of Enslaved Black Cidermakers

Isaac Granger Jefferson ca. 1845, blacksmith at Monticello and son of George and Ursula Granger. There are no images of his enslaved parents, who were both involved with cidermaking there. (Wikimedia public domain)

George Granger, or Great George as Thomas Jefferson called him, was an enslaved Black cidermaker on Jefferson’s Monticello plantation. The November 1st, 1799 entry in Thomas Jefferson’s Farm Book (Tracy W. McGregor Library of American History, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library) reads: “70 bushels of the Robinson & red Hughes…have made 120 gallons of cyder. George says that when in a proper state (there was much rot among these) they ought to make 3 galls. to the bushel, as he knows from having often measured both.”

To learn more, check out Darlene Hayes’ article, George and Ursula Granger: The Erasure of Enslaved Black Cidermakers.

How many apple varieties are there?

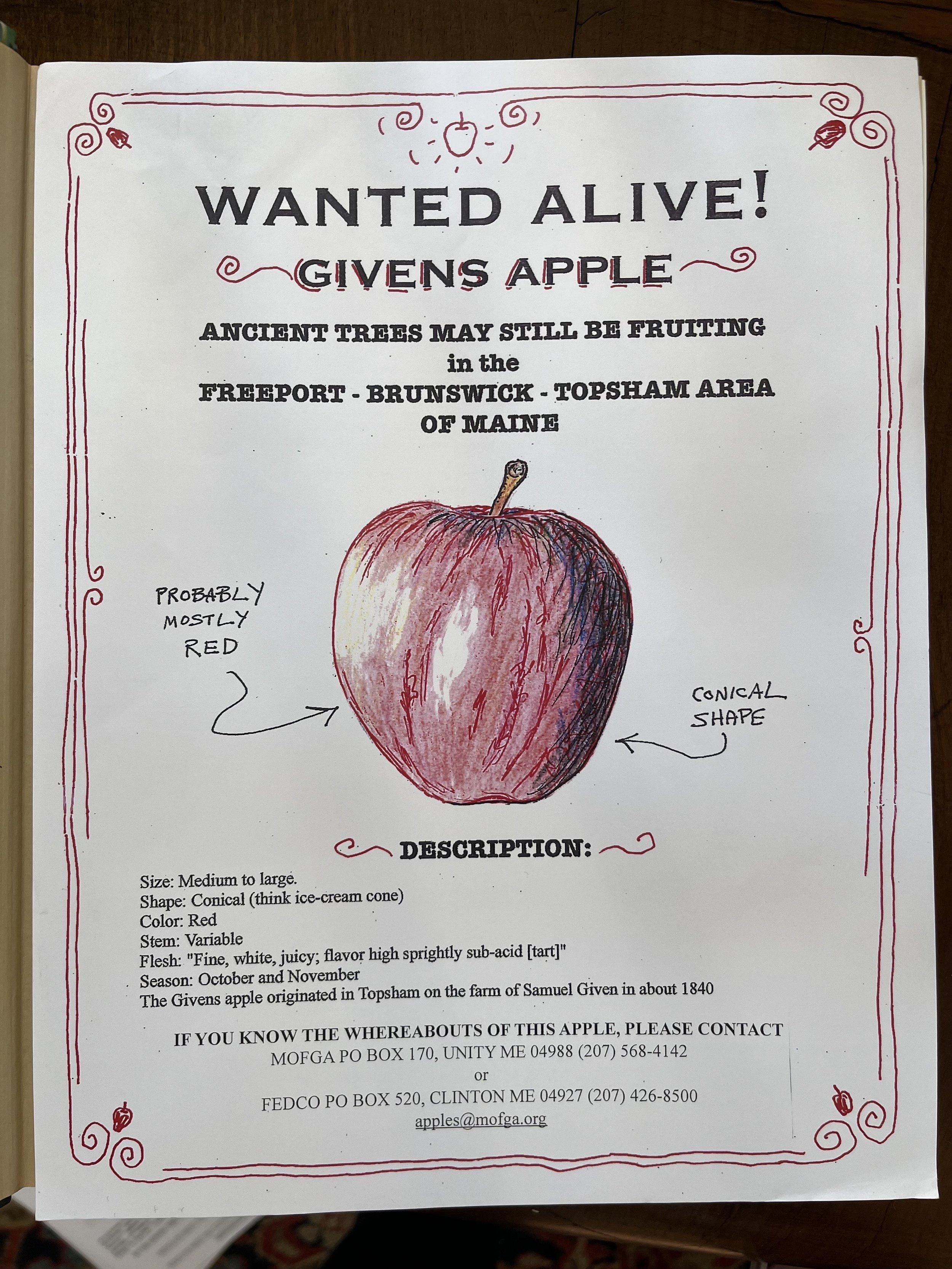

There are over 7,500 apple varieties in active cultivation around the world, but in North America alone, apple historian Dan Bussey has documented over 16,000 apples in his The Illustrated History of Apples in the United States and Canada. Many of these apples have gone wild, or “missing.” Here are some posters of “missing” apples on display at the Common Ground Country Fair in Maine (photos by Justine Paradis).

Links

George and Ursula Granger: The Erasure of Enslaved Black Cidermakers, by Darlene Hayes.

Cidermaker Soham Bhatt (Photo courtesy of Soham Bhatt)

Crab apples and polypores and homemade cider. Photos by Felix Poon.

Credits

Reported, produced and mixed by Felix Poon

Edited by Taylor Quimby, with help by Justine Paradis, Jessica Hunt, and Rebecca Lavoie.

Host: Nate Hegyi

Executive producer: Rebecca Lavoie

Music for this episode by Jharee, Kevin MacLeod and Blue Dot Sessions.

Our theme music is by Breakmaster Cylinder.

Outside/In is a production of New Hampshire Public Radio.

If you’ve got a question for the Outside/In[box] hotline, give us a call! We’re always looking for rabbit holes to dive down into. Leave us a voicemail at: 1-844-GO-OTTER (844-466-8837). Don’t forget to leave a number so we can call you back.

Audio Transcript

Note: Episodes of Outside/In are made as pieces of audio, and some context and nuance may be lost on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors.

Justine Paradis: Heads up, there’s a curse word in this episode, towards the beginning of the show. Okay, here’s the show.

Felix Poon: Let’s pop this bottle open!

[pop]

Justine Paradis: Opa!

Felix Poon: Opa, ayyy!

Justine Paradis: This is Outside/In, I’m Justine Paradis – and the other day, producer Felix Poon and I got into our studio closets at a very cool 10 in the morning to start the workday with an invigorating glass of hard cider.

[pour sounds]

Justine Paradis: Cheers!

Felix Poon: Cheers!

Justine Paradis: Mmm, that’s really dry, I like that.

Felix Poon: Yeah, mine too.

Justine Paradis: This one is kind of has a sort of floral edge to it that doesn't taste exactly like the fruit. Yeah, I don't know how to describe it.

Felix Poon: Yeah, I mean, I would say mine tastes like a rosé with but, yeah, with just a really subtle hint of Apple.

Justine Paradis: Both of our cider bottles are not like cider cans or like six packs. They're like wine bottles like, you know?

Felix Poon: Well, in a lot of ways, cider is closer to wine than it is to beer.

Justine Paradis: Because it’s fermented from fruit rather than grains like beer.

Felix Poon: Yeah, and also the taste of cider has a lot do with where it’s made. Like, cider has terroir, which is this French term that most people associate with wine. Justine, how would you define terroir?

Justine Paradis: Yeah, it's like the the flavor of a place coming through in the product, so the limestone of Burgundy, you know, appearing in wine or something… Placiness!

Felix Poon: Placiness, yes, the combination of soil and topography and the climate. All those things that go into the unique flavor of the wine.

But, it’s really the unique flavor that goes into the fruit that makes the wine. So you don’t even need to be talking about booze necessarily to understand the idea. Like, I spoke to a cidermaker named Soham Bhatt, and Soham says he first really understood terroir with another fruit altogether.

Soham Bhatt: Every spring, my dad would go to the Indian store and buy a box of mangoes. They were Marathon-brand mangoes from Mexico. And he would go there and buy this whole box, every year like a broken record, he would complain about the quality of the mangoes.

[MUX IN]

And it was like, there's no mango that's better than this Hafoos or Alphonso mango from the village that he grew up in, called Vulsar in Gujarat, India. And I never really believed him until I went there, and I had that mango variety and like it literally brought me to tears with how delicious it was.

Justine Paradis: I mean, that sounds amazing.

[MUX OUT]

Felix Poon: Yeah, totally, so his dad would really pine after this mango, but for, Soham he was born and raised in the US, so the place that he felt most connected to wasn’t India, it was New England, where he grew up. So, like, he likes mangoes, but what he really felt a deep affinity for were apples.

Justine Paradis: Yeah very strong New England fall apple association for sure.

Felix Poon: Yeah, and it was about ten years ago that Soham visited a cidery in Western Massachusetts called West County Cider. And that’s where he was inspired to start making his own. I went to this cidery last fall, which was part of this annual festival called Cider Days…

Woman: Welcome to Cider Days!

Felix Poon: …and I can definitely tell you - people at this festival don’t just like apples, they identify with them.

Bob Sabolefski: I think it definitely does have a cultural identity, I don’t know if anyone can explain it today, but the apple pie – is pretty damn fucking American.

Justine Paradis: I appreciate a man who curses.

Felix Poon: Yeah, even people who didn’t grow up here had similar thoughts. Here’s a German American woman who told me that Germans love apples too, but Americans take it to another level?

Woman: But this apple cult, is not so much German.

Felix Poon: Cult? A cult?

Woman: Yeah. Don’t you think it is, kind of, at this point?

Felix Poon: A little bit, yeah.

Woman: It’s a wonderful tradition...

Justine Paradis: I definitely think that the fall trope… like person wearing knee high…

Felix Poon: There’s, like, knee high boots.

Justine Paradis: Yeah, exactly.

Felix Poon: Flannel shirts. Yeah.

Justine Paradis: And one of those sort of suede bucket hats, you know?

Felix Poon: Yeah, it's such a caricature. But that's kind of sometimes how cultural identity boils down to this. Like, it's, it's just this all-American thing, kind of. But here's the thing: the apple tree isn't native.

Soham Bhatt: Apples aren't from here. Cranberries are native, blueberries are native, but not apples.

Felix Poon: This is Soham again.

Soham Bhatt: You know, apples are from Kazakhstan. And so, in many ways, apples are Asian immigrants. For me, it's an exciting way to think about it… that I'm more akin to an apple than. than some other people might be.

[Theme stems rise]

Felix Poon: Today on Outside/In, the migration story of Malus domestica, the domesticated apple. A foreign fruit that has come to symbolize American heritage.

Justine Paradis: What does that story tell us about migration in American history – but also, what does that story tell us about new immigrants, like Soham’s family’s migration from India.

[Theme stems out]

<<1st Half>>

Felix Poon: Okay so the migration story of Malus domestica, the domesticated apple, some of us might be familiar with. It begins in the apple’s ancestral home around Almaty, or Alma Ata, Kazakhstan.

[MUX]

Alma-ata actually means “father of the apple,” and this is a city where wild apple trees sprout up in the cracks of sidewalks. And all around outside the city are forests of wild apple trees, up to fifty feet high and as big around as oak trees.

Justine Paradis: Apple paradise!

Felix Poon: Anyways, people eventually took apples west into Europe along the Silk Road and then here to America with the early colonists. And cider was really common in colonial America.

Ben Watson: I mean, everybody drank cider, literally everybody. Even children would drink it, and it was seen as a healthful beverage

Charlie Olchowski: A common household in colonial America, you know, stored several barrels of apple juice when… It was sweet when it first went into the basement, but by the end of the fall into the winter it converted to alcohol.

Felix Poon: That was Ben Watson and Charlie Olchowski, two cider experts I talked to at the cider festival.

So back in colonial days, apples were a matter of survival. It gave the colonists something to eat, but it also gave them something to drink, because most water sources close to settlements were polluted. Beer was the beverage of choice back in Europe where they had the same problem, but most early attempts at growing barley and hops in America failed, ehereas apple trees could be grown almost everywhere.

So cider was so common, and valued, that it became a unit of currency. Barrels of hard cider were used to pay people like doctors, teachers, and construction workers.

Justine Paradis: I just love how deeply boozy American history is.

[MUX IN]

Felix Poon: And up until the late 1800s, apple trees were mostly grown by seed in America, and this is an important point, because apples are heterozygous, they don’t grow true to seed, which means that if you want to plant a specific kind of apple tree, you have to graft it. And grafting is this technique where you cut a branch from one tree and basically stitch it onto another.

But it’s a different story if you’re planting from seed. The apples you get from the new tree will be completely different from the ones it came from.

Now there’s usually around 5 to 10 seeds in every apple. Your average tree has hundreds per harvest… which means, a lot of trees were being planted in America, and each one was completely new.

Felix Poon: And each one was trying to take root and thrive in its new environment.

And this is the part of the story where you usually hear about one particular man, who’s famous enough to have been turned into a Walt Disney folk hero. Johnny Appleseed.

[DISNEY CLIP]

Narrator: But lately little Johnny here would feel a stir in the air, the rumbling rolling underbeat of restless men and restless feet.

Singing: …rolling west, there’s plenty of room for you…

Felix Poon: The Disney version of Johnny Appleseed was this man who single-handedly brought apples out west into the frontier, bringing hope and courage to the pioneers as they settled the great unknown beyond the vast wilderness.

Singing: So get in the wagon rolling west, seeking the land that’s new…

Felix Poon: But it wasn’t just Johnny Appleseed and white settlers who planted apple seeds while they migrated across the country. It was actually Indigenous people who first brought the apple west.

I spoke to Susan Sleeper Smith, author of the book Indigenous Prosperity and American Conquest, and she says the Neutral and Erie tribes in today’s upstate New York, picked up apple cultivation from Jesuit missionaries, and then they migrated westward.

Susan Sleeper Smith: They were forced out by the Iroquois and they moved along the shores of Lake Erie.

Felix Poon: And they arrived in the area around present-day Detroit, which is where it’s been documented that these tribes cultivated apples…

Susan Sleeper Smith: Not just in their villages, but particularly along the river ways where the apple trees grew in abundance.

Justine Paradis: What year was this?

Felix Poon: This was documented in 1675, more than a century before Johnny Appleseed and a wave of white settlers ever arrived on the scene.

Justine Paradis: A whole century.

Felix Poon: Yeah, and then there was a French Canadian military captain, who documented Indigenous apple cultivation on an island on Lake Erie just outside Detroit.

Susan Sleeper Smith: And the island had apples, which had fallen to the ground, which were almost a foot deep and they were the most delicious apples he'd ever tasted.

Justine Paradis: That's hilarious. I mean, this is like wine, people would stomp the grapes, right? Did they ferment cider from these apples?

Felix Poon: That’s a good question, Susan says they mostly used the apples for eating and for flavoring stews. They did make apple juice, but she says they didn’t need to make cider since, unlike white settlers, they knew where the clean water sources were.

[MUX SWELL]

Felix Poon: But apples were also used as a tool for Western expansion. Indigenous people were being forced out by the US government and white settlers. And in some places, land grants in newly forming states required settlers to have apple or pear trees on their property as a condition of their deed.

And this is really where Johnny Appleseed comes in, whose real name was John Chapman.

Narrator: And as more and more pioneers come to push back the forest, the kindly deeds of little Johnny Appleseed spread throughout the land…

Felix Poon: Chapman traveled west ahead of the settlers, and grew an untold number of apple trees from seed. Although, according to Susan, Chapman probably also took over abandoned orchards that were cultivated by Indigenous people.

Justine Paradis: Typical.

[MUX IN]

Felix Poon: So, by the time settlers arrived, Chapman’s trees were ready to sell to them. Then he’d go back to Pennsylvania, pick up more seeds and repeat the process. Back and forth, back and forth.

And, Justine, when you think of Johnny Appleseed, what do you imagine?

Justine Paradis: Oh, what’s that guy’s name, I think about Paul Bunyan. I guess I picture mostly a cartoon.

Felix Poon: Yeah, he’s often portrayed as this dirt-poor guy who's walking around barefoot, wearing a tin pot for a hat.

Justine Paradis: A tin pot?

Felix Poon: Yeah, that’s so weird, why is he wearing a tin pot?

Justine Paradis: Why is he wearing a tin pot, that seems like… heavy and inefficient.

Felix Poon:, in the Disney movie it’s like song and dance and this angel is like: Here’s your bonnet, and you know, flip it upside down and then you can cook things on it.

Justine Paradis: Oh, so the idea is that it’s more efficient.

Felix Poon: Right, it’s multipurpose.

Justine Paradis: Yeah [laughs].

Felix Poon: So knowing all this, would it surprise you to hear he actually made a bunch of money off these apple trees?

Susan Sleeper Smith:: He, at the end of his life, has far more lands that he's holding than any other settler around

Felix Poon: 1,200 acres throughout Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana, to be exact, which is a lot of land.

[MUX SWELL]

Anyway, growing apples from seed was the norm because seeds were plentiful… and portable.

But the thing about growing from seed, when it comes to the flavor of the apples, is that they’re usually really tart. In fact, Henry David Thoreau once wrote that they’re, quote, “sour enough to set a squirrel’s teeth on edge and make a jay scream,” unquote.

Justine Paradis: Oh yes, the classic idiom sour enough to set a squirrels teeth on edge.

Felix Poon: Is that a classic idiom? I've never heard it.

Justine Paradis: I am being facetious.

Felix Poon: (laughs)

[MUX OUT]

Felix Poon: Anyway, so almost all of these new apple trees grown across the country were not ideal for eating, but they were perfect for making cider.

But, things changed with industrialization – lots of Americans moved off family farms, and into the cities in the late 1800s. Orchards were abandoned, and beer became the beverage of choice, especially with the arrival of European immigrants who brought better beer-making techniques over.

Then prohibition happened, and apples became almost exclusively for eating. Cider all but disappeared, and it was basically forgotten.

[ambi mux]

But then, over a half a century later, it started to make its comeback. West County Cider was the first modern cidery to open in 1984 in MA. And then Woodchuck Cider came along in Vermont.

[YouTube]

Woodchuck guy: Our first cider was Woodchuck Amber, which we originally bottled in a small two car garage…

[Youtube]

Angry Orchard: Like the taste of fresh apples? Try an Angry Orchard hard cider…

And since then, cider has consistently been one of the fastest growing segments of the alcohol industry.

Angry Orchard: …When you’re looking for something a little different… Angry Orchard hard Cider. Explore the orchard.

But what if that long period when cider disappeared in the 20th century was actually a blessing in disguise? What if, in order to flourish, the future of cider has to be divorced from its past?

Soham Bhatt: A lot of producers nowadays at least recognize that cider being forgotten was a good thing.

Felix Poon: That’s after a break.

[MUX SWELL]

Felix Poon: Outside/In is a listener supported podcast. We rely on listeners, like you, to donate to support the show. It’s quick and easy – just go to outsideinradio.org and click “donate.” And thank you.

<<MIDROLL>>

Justine Paradis: Welcome back to Outside/In. I'm Justine Paradis here with producer Felix Poon. And today Felix is talking about cider and why cider maker Soham Bhatt thinks that cider being forgotten in the 20th century was actually a good thing.

Felix Poon: But before we get to that, Justine, let’s spend some time talking about apple varieties. And I wanna play a game first that’ll tell me what your favorite varieties are.

Alright, which variety do you like better? McIntosh or Honeycrisp?

Justine Paradis: Honeycrisp.

Felix Poon: Honeycrisp or Gala?

Justine Paradis: Uh…Ok, I’m gonna stick with Honeycrisp.

Felix Poon: Honeycrisp or Pink Lady?

Justine Paradis: I like Pink Lady a lot. I guess Pink Lady.

Felix Poon: Pink Lady is the winner here, ding ding ding!

Justine Paradis: [laughs] I mean Pink Lady should win, it’s a good name!

Felix Poon: Yeah, totally. Anyway all of these common varieties are from grafted trees. And the interesting thing about grafted trees is that all of them can trace their lineage back to a single tree that was once grown from seed. Like, take the Red Delicious for example. The first Red Delicious tree was discovered on a farm in Iowa in 1872.

[MUX IN]

And this farmer kept whacking this one tree. He was like, I don't want this here, and he just like, whacks it. It comes back, whacks it again, and eventually he's like, All right, I guess I'll keep this. And then, you know, years later, once it fruited, he tried it. He was like, Oh, this is really delicious.

Justine Paradis: [laughs]

Felix Poon: And he named it the Hawkeye. But there was this apple nursery that was looking for, like,a really amazing apple, and they had a name for it, already. “Delicious.” They had that name prepared and they were just looking for the apple to give that name to. And so it was through this apple competition that that this farmer submitted his Hawkeye Apple to them. They're like, “Oh, this is the one.”

Justine Paradis: Who will be crowned the “Delicious?”

Felix Poon: They crowned it “the Delicious.”

So, all varieties at one point had to be discovered by chance like this. And this process is why some have called apples “the democratic fruit.”

Like, you plant apple seeds in the same soil, and any seedling has an equal chance at greatness, like the Red Delicious, and the Golden Delicious. It doesn't matter your lineage or origin, America will recognize and celebrate great apples.

Like, Michael Pollan writes in his book The Botany of Desire, “what native plant zealot would dare to challenge the right of such trees to call themselves American now?”

[MUX OUT]

Justine Paradis: I mean, as iconic as it is, I kind of also feel like the Red Delicious is the most maligned apple as well. Like, for good reason, in my opinion, they’re not very good!

Felix Poon: Yeah, Red Delicious apples are pretty bland, and mealy. But that’s because of how we’ve selectively bred them over time. Because even with grafting, growers are still cutting from branches that look the most red, and have the toughest skin so they’re easier to transport. We’ve essentially evolved them for the mass market. But this is very much an American story though, right?

Justine Paradis: Do you mean like, the homogenization of so many different apple varieties down to just a handful that are good for the grocery store?

Felix Poon: Right, that’s kind of endemic to American agriculture right?

Justine Paradis: Or like culture, like, wipe out your difference. Like, fit in!

Justine Paradis: Have you ever been to the common ground fair in Maine?

Felix Poon: I have not.

Justine Paradis: It's, like, huge, and it's in the fall and it's been going for decades. One time when I went, I went to this stand of, like, heirloom apples that were sort of, like, very localized in Maine. And they had these missing posters kind of like wanted posters for, like, a missing cat or something? But instead of the cat it was missing all of these varieties of apples, like “last seen in this county in 1920.” Um, because a lot of these varieties, those heirlooms, have gone out of existence.

[MUX IN]

Felix Poon: Honestly, finding lost apples is something I could totally see myself getting into.

Justine Paradis: Oh I love that for you. Second career.

[MUX SWELL]

But apples aren't the only heterozygous species in our story. The other species are humans. We are not like our parents or grandparents.

And just as generational change happens with apples, especially through the process of migration and changing environments, we can see something like that with humans too, and how culture shifts, and changes.

[MUX IN]

Take cidermaker Soham Bhatt, who we heard from in the first half of the episode. His story is a great example of this. So, Soham’s parents immigrated to the U.S. from India, and his whole family loves food. They love eating it. They love making it. And growing up. Soham’s parents got really good at making one dish in particular.

Soham Bhatt: There's a kind of famous street food in India called panipuri.

Felix Poon: Panipuri is this spherical fried bread, about the size of an egg shell, and you fill it with stuff like potatoes, lentil, some different chutneys.

Soham Bhatt: It's one of these things that if you grew up eating it, it's like, it's a very, very important kind of nostalgic taste memory for, for them, a comforting one.

Felix Poon: And his parents and relatives put a lot into this, putting together essentially this assembly line for making hundreds of these.

Soham Bhatt: You needed somebody to to make the main dough. Then you needed somebody to make tiny little balls out of it. Then you needed somebody to roll the little balls into discs, you know, the size of a silver dollar, and then you needed somebody to fry them.

Felix Poon: Soham was only about five or six at this point.

Soham Bhatt: My rule was getting all the, all the puris that didn't puff – the flat ones, the ones that were like little crackers. Those were those were our those were our snacks.

Felix Poon: Soham says he's always been a tinkerer in the kitchen, like kneading his own bread, fermenting his own yogurt — it’s a relationship to cooking he picked up from his parents. And he also learned to value seasonality from them.

Soham Bhatt: You know, for them, the mango season or the guava season are short two or three week windows.

Felix Poon: Growing up in America, Soham identifies more with fruits that you find here.

Soham Bhatt: For me, it's like, oh, like tomato seasons here. And I'm going to really appreciate tomato season while it's here and apple seasons here, and I'm going to appreciate the apple harvest.

Felix Poon: Soham has a foot in both cultural worlds, and what you eat and drink is a big part of that for Soham. Having a foot here means connecting to something that's literally from the soil we walk upon: apples. Having a foot there in India means eating something that Soham had with his parents as a kid like, say, a spicy dish of goat neck biryani.

[MUX OUT]

Soham Bhatt: All these foods that we eat, you know, like Nigerian, like, jollof rice, spicy dumplings and gyoza and Thai food, we look up, you know, recipes for for something Filipino or whatever it might be.

Felix Poon: Yeah

Soham Bhatt: There's a place for that kind of food with cider that's very natural, and the best thing about it is that it's local. So you get you can kind of connect both to this global perspective and also with where you are.

[MUX IN]

Felix Poon: Soham makes these kinds of food pairings in his taprooms. He partners with ethnic food pop-ups to make sure the food reflects the heritage of a diverse clientele. Soham says that cider can reflect this future-forward identity, rather than a nostalgia for a colonial or old frontier identity.

Justine Paradis: Food pairings and alcohol make a lot of sense to me, like that's how a lot of alcohol is treated right? Like wine and and cheese or a heavier wine with, like a meat or a stew or something. So the sweetness of the cider plus spiciness, just, it makes a lot of sense to me. I don't know – you just, you taste new things in the cider as well when you pair it with food.

Felix Poon: Yeah, I think what Soham is doing is he's doing his own branding campaign for cider.

[MUX OUT]

He’s trying to avoid this cultural baggage that he says beer has.

[Youtube commercial: Miller Lite]

Narrator: Man up, and choose a light beer with more taste…

Narrator: Budweiser presents, real men of genius…

Felix Poon: Beer is marketed for the blue collar all-American man who likes pickup trucks, hot babes, and Sunday Night Football.

Justine Paradis: Well, also they could very just as easily be associated with, like Belgian monks, you know? But it's not. Like, asceticism.

Felix Poon: Yeah. And then there's wine that has this cultural elitism to it. But Soham says cider doesn't have any of that. He points to market research that shows cider consumers are evenly split between men and women, whereas beer skews male and wine skews female. And among cidermakers themselves there are a lot of women in leadership roles as cidermakers, agricultural researchers, and on the American Cider Association board.

Justine Paradis: Yeah, I mean, I enjoy wine myself, but I also get really annoyed by the like “rosé all day.” Like, like “mom needs her wine” stuff. It's like, Even if you're like, I like rosé and I'm a woman, it's like, I don't want that to be the commentary.

Felix Poon: Yeah

Justine Paradis: Just like a man should be able to enjoy a beer without participating in masculinity culture, you know?

Felix Poon: Right? Totally. I love rosé. I could drink rosé all day.

[MUX IN]

Justine Paradis: There you go. You can own that phrase if you like.

Felix Poon: I will. Thank you, Justine. Yeah, and this is what Soham meant when he said he's glad cider was forgotten in the 20th century. It didn't get shaped by all these terrible ad campaigns, and, you know, social media…

Justine Paradis: Just got to skip it.

Felix Poon: Yeah, exactly. So, there’s this opportunity to associate it with diverse backgrounds.

Justine Paradis: So, as far as the landscape of cider, and the industry, is there a lot of diversity in terms of flavor as well?

Felix Poon: Yeah, Soham’s pretty focused on that. He’s not interested in making cider that tastes like what they drank back in the day. For him it’s about using modern winemaking techniques – like chemical stabilizers and temperature control; it’s about experimenting with the thousands of different apple varieties out there, or infusing your cider with blueberries or cranberries.

Justine Paradis: Yeah It sounds like a lot of experimentation, just like the craft beer movement too right? And now there’s way more options out there than just your classic lager or New England IPA .

Felix Poon: Yeah, it’s about making all sorts of new things, to make sure that there’s something for everyone.

[MUX SWELL]

But I think, on the flip side, the fact that cider was forgotten kind of makes the nostalgia of cider even more potent. Like as cider has been getting rediscovered in the past couple of decades. A common kind of branding strategy was to bring up how the founding fathers all drank cider. How George Washington and Thomas Jefferson fermented their own, and how John Adams drank cider with breakfast every day.

[MUX OUT]

Justine Paradis: Yeah, and even some of the artwork is, sort of, on, you know, labels sort of calls back to that.

Felix Poon: It's very, yeah, feels very colonial right?

Justine Paradis: Vintage.

Felix Poon: Yeah, yeah.

Justine Paradis: And then, nostalgia – like you imagine like, oh, was Thomas Jefferson making and pressing his own cider? And no, he was not.

Felix Poon: And this is a conversation that's been happening in the cider community, that this romanticization of colonial times often leaves out Black cidermakers from the story. Like Jefferson's enslaved cidermakers

[MUX IN]

Jupiter Evans, George and Ursula Granger. And by filling in these gaps in cider history, the industry is saying that Black people and Indigenous people are a part of this story too, part of this ancestral and cultural heritage.

But for Soham, he doesn't see himself in this country's heritage.

Soham Bhatt: I mean, there are people here in the Northeast that can probably link their their family history to the colonial period. And, by all means, like, that actually is their heritage. You know, but it's weird for me to, to use the word heritage because it isn't, you know? It just simply isn't my heritage.

Felix Poon: At the end of the day, Soham doesn’t think enjoying cider should even be about heritage.

Soham Bhatt: Why did it go away? You know, like we can, we can point fingers at beer or whatever it might be. Or Prohibition. But, like, it's not part of the cultural consciousness in the way that beer is. It was truly forgotten for some reason. Maybe because it wasn't that good.

You know, and now, we're living in a modern era where we have access to knowledge technology, varieties that allow us to, like, invent new ways of making cider that people actually like and they're really excited about.

[MUX IN]

And so I'm more about embracing that kind of forward-looking perspective than I am about the, the kind of backward-looking perspective.

Justine Paradis: Felix, thank you for this really interesting reporting on cider.

Felix Poon: My pleasure.

Justine Paradis: And, actually, before we go, Felix, you actually made your own cider, during your reporting for this story, right?

Felix Poon: Yeah, it’s not that hard. What I did was I actually picked a bunch of crab apples from a nearby park. I washed them with my roommate.

SFX

He snuck in a bite . I juiced them with my juicer. And then I poured that juice into a glass jug and put an air lock on it, which is this kind of zigzag tubular thing that lets air escape but it doesn't let any air… to get in.

Justine Paradis: And… how did it go, what did it taste like?

Felix Poon: Well, we’re about to find out!

Justine Paradis: Are you serious?

Felix Poon: yeah, can you see this?

Justine Paradis: Yeah it looks like the sediment has settled to the bottom, it’s pretty amber and clear though. Take a swig!

[Drinking tape]

Felix Poon: Hmm. It’s… uh…

Justine Paradis: So, for the full review, visit our website, outsideinradio.org.

Felix Poon: Yup, roll to credits!

[Fake theme ending]

Felix Poon: No, it’s a little sour, there’s some acidity here.

Justine Paradis: Would you bring this and serve it to a friend?

Felix Poon: I have to say there’s a funky taste in here. So probably not.

Justine Paradis: I think it’s a valiant first cider.

Felix Poon: Thank you, thank you Justine.

<<Postscript>>

Felix Poon: So I’m gonna recommend to you, our listeners, to get in on the fun, and maybe give this a try yourself. if there aren’t apple trees around you, you can get unpasteurized sweet cider from the store, and throw some yeast in that to ferment.

Justine Paradis: We will put a link to a cidermaking guide in the show notes.

Felix Poon: And if you want to learn more about the story of cider, I recommend checking out a couple articles. One is about the Black cidermakers George and Ursula Granger; and there’s another article by cidermaker Melissa Maddens. Melissa only uses foraged apples in her cider. She does that as a way to reflect on her relationship to the land that she lives on, which Indigenous people were pushed out of.

Justine Paradis: All that and more you can find in the show notes.

CREDITS

Justine Paradis: This episode was produced, reported, and mixed by Felix Poon. It was edited by Taylor Quimby, with help from me, Justine Paradis, Jessica Hunt, and our executive producer, Rebecca Lavoie.

Felix Poon: Special thanks to Darlene Hayes. She’s the editor of Malus Magazine and author of George and Ursula Granger: The Erasure of Enslaved Black Cidermakers. Thanks also to Matthew Festa. And thanks to all the cidermakers I talked to at Cider Days – Ben Clark, Ben Watson, Charlie Olchowski, Judith Maloney, William Grote, Chris Gayzaks, and Carol Hillman.

Justine Paradis: Our theme music is by Breakmaster Cylinder. Additional music by Jharee, Kevin MacLeod and Blue Dot Sessions. Outside/In is supported by listeners like you. There’s a link to donate in the show notes. You can also go to outsideinradio.org and click “donate.”