Stay In Your Lane

If you ask John Forester, there’s a war being fought, between the forces that want to eject cyclists from the roads, and those that want to preserve their right to ride. According to him, it’s been underway for at least a century, and environmentalists and cycling advocates have all been co-opted by the car lobby.

The story of one cycling advocate’s quixotic battle against “motordom”, and one of its favorite anti-cycling tools… the bike-path.

I’ve been riding a bike for most of my life. I used to ride two miles to school on a two-lane state highway with 50 mile per hour speed limits, a road friends' parents were aghast I was allowed to ride on. Around age twelve, as a Boy Scout, I completed the cycling merit badge, which included a ride where a whole group of middle-school boys and our parents toodled around the entire circumference of the mighty lake Winnipesaukee. (This is a terrible bike ride that I don’t recommend.) After college, I took up bike racing and got up to all sorts of silliness both on and off pavement.

But more importantly for this story, I ride my bike to get around. I ride to work. I ride to run errands. I ride to get groceries. Riding for transportation just makes infinite sense to me. It lets me get a bit of exercise even on days when I have no time, and I find I’m grumpier and my mind is foggier any day that I haven’t ridden to work. It saves my family a ton of money that we only pay to gas up, register, and maintain one car for the two of us. And I like to believe that me getting my car off the road has positive effects for drivers too, by eliminating one more car from that line of traffic and freeing up another parking spot.

It’s hard for me to not evangelize for getting out of the car and getting to work on foot or on a bike, whenever you can.

But it’s easy for me. I’m in good shape. I’ve been riding my whole life and am comfortable with cars whizzing past at high rates of speed. Hell, I don’t even have to put my feet down when I stop at a traffic light. As such, a bedrock assumption that I’ve always held is that cyclists would be better off if we had our own infrastructure that separated bikes and cars. I mean, not everyone is going to be willing to suit up for battle against automobile traffic. Which is why it’s no surprise to me that cycling groups push for more protected bike lanes.

For this reason, when I learned about John Forester, I became just another in a long-line of cyclists shocked to learn that one of the nation’s most prominent cycling advocates thinks that building infrastructure for cyclists is a bad idea.

Who Is John Forester?

John Forester was born in 1929 in London, but moved to Berkeley, California when he was ten. He was an industrial engineer whose father wrote The African Queen and the Hornblower series, and John has the benefit of receiving a part-share in the royalties from those books. John had a very similar history to my own: rode his bike to school, and eventually got into racing and long-distance touring.

In 1972, his then home city, Palo Alto, passed an ordinance that would require all cyclists to ride their bikes on the sidewalks. This was a bald-faced attempt to kick us off the road, and John decided to kick up a stink. In an act of civil disobedience he rode in the street and when a police officer pulled him over, he told the officer, “I’m not going to obey you. What are you going to do about it?” The officer wrote him a ticket and they went to court, but before John exhausted the last of his appeals the city decided to overturn the ordinance and let cyclists back into the road.

This confrontation kicked off a lifetime of activism for John Forester. He started to pay attention to state transportation committees, realized that there are no cyclists on these committees and he started rallying together cyclists to oppose these rules. “I got myself a mimeograph machine, and informed California cyclists. Everyone I knew,” John remembers, "And we had a great big war."

John's Philosophy

This war, according to John, was waged against this big, shadowy, multi-tentacled beast called “motordom”. This moniker is not John’s invention, it was the title of a political publication produced by the automobile association of New York State, but John has adopted it as a catch-all term for car drivers and their advocates. (“It has to include, among other things, the Highway Patrol,” John points out.)

The two primary ways that motordom is pushing this agenda, according to John, is through “mandatory sidepath laws” and “far to the right laws”. The former specifies that when a bike lane exists cyclists must use it, while the latter demands that bikes stay right so that cars can squeeze past them in a travel lane. He says the “sidepath laws” are being pushed by drivers who want to exclude cyclists from the road “to make motoring more convenient.” That form the basis for his opposition to protected bike lanes. Whenever a cyclist advocates for this infrastructure, John maintains it is because they have been cowed by motordom; tricked into believing ideas that are contrary to their real interests.

He refers to this strain of rider as advocating cyclist inferiority cycling. “Subservient to motorists, cringing along the edge of the road, frightened of being hit from behind.” On the other hand, he insists, you have “true cyclists, “Enthusiastic cyclists — more men than women — in cycling clubs, who obeyed the rules of the road instead.”

John’s talking points on this front are incredibly consistent, and involve a little bit of verbal jujitsu: there are the cringing gutter-huggers versus the cyclists who obey the rules of the road. This construction suggests that any cyclist who is intimidated by speeding automobiles is also breaking the law, which is not prima facie true. Nonetheless, John insists that these cyclists — who he also refer to as incompetent cyclists — are the only ones who want their own infrastructure.

“Motordom doesn’t have to say anything anymore,” he asserts, “because the bicycle activists — environmentalists and whomever you like... anti-motoring people — they want side-paths. Because that’s what the ignorant people want. And when I say ignorant I mean it. The people who don’t understand.”

Why Did John Forester Matter?

John’s impact was two-fold: on cyclist education and on design guidelines. On the first front, he wrote a book, called Effective Cycling, which for decades was the go-to handbook for cycling safety classes. (Heck, it’s still recommended reading for Boy scouts completing the cycling Merit Badge.) His school was to teach people to ride in traffic, and to act as if they were a car whenever they reached an intersection. “Cyclists fare best when they act and are treated as drivers of vehicles.” Indeed, essentially every bike safety course you can find to some degree will teach you vehicular cycling ideas. Exhortations like "take the lane," "obey the rules of the road," "don’t ride on sidewalks" are all straight from John's school of cycling. (And I want to be clear right here, I personally don't disagree with using any of these techniques.)

In fact, this is how John believes cycling advocates can get more people on bikes. “The proper thing to have done was to have encouraged those people who they think might take up cycling to obey the rules of the road. Learn how traffic operates and therefore operate safely, and confidently and cheerfully,” he says.

While I don’t believe John's vision of safe cycling is an entirely un-problematic (more on that later), this particular piece of his legacy seems to me to be largely a good. Certainly the lessons I learned from the cycling merit badge have helped to keep me safe on roads that are full of speeding two-ton machines, occasionally piloted by people who actively dislike that I’m on the same street as them.

But John has a more problematic legacy, stemming from his dogmatic belief that all bike paths are part of a conspiracy to limit cyclists’ right to ride in the road. In 1974, an organization called AASHTO – drawing from experiments in bike infrastructure design carried out by University of California in Davis – wrote the nation’s first design guide for cycling infrastructure. That guide recommended separated, protected bike lanes in certain circumstances. This attracted John Forester’s attention, and in response he helped write a California guide that insisted that separate bike infrastructure is unsafe for cyclists. Next, when AASHTO re-wrote its guide in 1981, John submitted prolific public comments and AASHTO largely adopted the language from his guide and recommendations.

It wasn’t until 2012 that AASHTO finally conceded that some separate bike infrastructure might improve safety.

How important are these guidelines? “The AASHTO guidelines dictated what got built,” says Anne Lusk, a researcher with the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health. She says conservative state highway engineers are wary to exceed what AASHTO recommends, driven by concerns that they’d be courting a lawsuit if someone was injured on infrastructure that doesn't follow the standards.

“So when you track the AASHTO guidelines back, for bicycle facilities, and you realize they were written by men sitting around a table deciding what worked for them as vehicular bicyclists, and then that would go to the states and the states would build, sitting around a table deciding what was working for them… what we ended up with was decades of bicycle facilities that essentially were designed by John Forester, because he wrote the first AASHTO guidelines.”

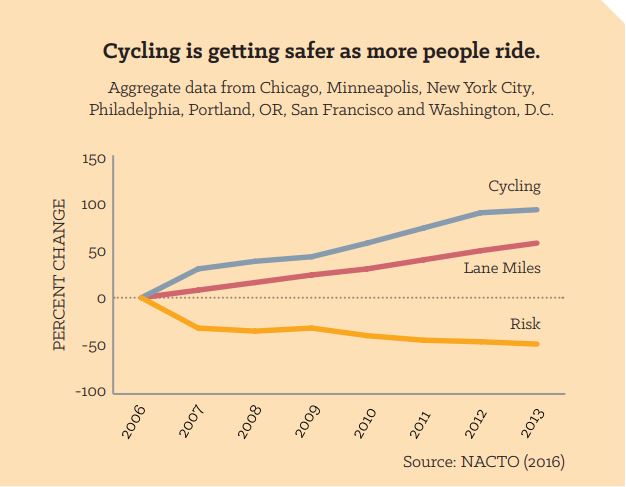

In other words, all of the new bike infrastructure that is being built in cities like New York and Portland and Minneapolis — infrastructure that has been found to be associated with more people riding bikes and a lower rate of crashes and injuries – might have started getting built back in the 70s and 80s.

The Trouble with John’s Philosophy

The trouble with John’s philosophy is there is little to no evidence suggesting that he’s right. John likes to cite a study that was conducted in 1974 by Ken Cross. This study found that overwhelmingly cycling accidents occurred at intersections, but only 7% occurred because of cars overtaking cyclists and hitting them from behind. In John’s mind, the conclusions to draw from this data is obvious. First, any cycling infrastructure that doesn’t address the danger cyclists face at intersections will not actually improve safety. Second, a barrier that ensures vehicles can’t cross into a bike lane won’t actually prevent many crashes.

What’s interesting here is that John might be right on both counts, but still be wrong to conclude that bike infrastructure shouldn’t be a priority. The reason for this is that it has long been observed that the more people who are out cycling the safer cycling becomes, because drivers become accustomed to dealing with bike traffic. There’s a safety in numbers effect, and that alone might be the most important safety improvement for all cyclists.

But John goes beyond simply arguing that bike lanes don’t make us safer, he actually believes that bike paths are less safe. Part of his evidence is a “test” that he himself conducted in which he rode his bike along a sidewalk as fast as he could, and counted how many times he had close calls with cars and pedestrians. (You should read his own account of this. It’s about halfway down, called “actual sidepath test.”) This is, of course, not how science is done. It would be like concluding that because one speeding motorist had an accident, that therefore any road that can't be driven on at 100 miles an hour is unsafe.

John does cite a handful of studies that he says prove his conclusion as well. But it's not a given that these studies stand up to scrutiny. For instance, Anne Lusk reanalyzed the data from one of the studies, and found that the higher crash rate was entirely attributable to cyclists traveling in the opposite direction as the cars, and otherwise riding on the sidewalk was just as safe as out in the road.

This does not necessarily mean that the studies don’t tell us anything, but rather that there are not data sources for cycling accidents that are good enough to draw strong conclusions about how to design good infrastructure. A recent review of the studies on bike facilities pointed out while crash data exists “the quality of that data is often lacking due to problems of under-reporting and reporting bias.” Because it’s hard to create a randomized, controlled trial in the real world, it’s actually tough to say with any certainty what kinds of infrastructure is safest.

But in the end, it might not matter. That same review points out that thanks to the safety in numbers effect the relevant question might actually be, “how much emphasis should be placed on designing for safety alone versus designing facilities more people will want to use.”

There’s another problem with vehicular cycling that John typically doesn’t acknowledge: some roads are objectively more dangerous than others and insisting that cyclists either ride in the road or don’t ride at all reinforces already existing inequities in the safety of the roads people have access to. This is where I think the school of vehicular cycling also has the potential to be pernicious.

“I really started to notice what neighborhoods I would be in when I would be riding in a bike lane, and what neighborhoods I would be in where there wasn’t a bike lane at all,” remembers Tamika Butler, former head of the LA County Bicycle Coalition, “Or what neighborhoods I would be in where we would actually feel safer getting on the sidewalk, and then all of a sudden the sidewalk would end and it would turn into a freeway entrance.”

Minority communities tend to live in areas where the roads are less safe for cyclists. Black and Latino cyclists are killed at a rate that’s 30 percent and 23 percent higher than white cyclists. Insisting that the only way to get more people to ride bikes is to teach them to ride like vehicle drivers is tantamount to sending more minority cyclists into the teeth of objectively more dangerous infrastructure. But of course, members of these minority communities aren't stupid, and often opt to ride on the sidewalk instead of facing traffic. Sidewalk riding is also illegal in many cities, and this may help to drive the “biking while black” effect: where minority neighborhoods get twice as many cycling citations as white neighborhoods.

These types of arguments tend to hold little appeal to vehicular cycling adherents, and Tamika has a theory as to why.

“It was actually a white guy who first told me this,” she remembers, “One of the things you’re gonna run into is that there’s a lot of guys just like me, who have never faced any sort of oppression or discrimination in our lives until we’ve been on a bike. And so when someone tells us we have to be in a bike lane, or we have to wear extra equipment or that if we get hit it's our fault not their fault… we’ve never experienced that. So when that happens to us for the first time, and when we feel like we’re being blamed even though often-times we’re the victim, this feels like a social justice to us. So you’re really gonna struggle talking about social justice because that’s what it going to mean to that group of people.”

John’s Abuses

While you might agree with John Forester’s ideas about separated bike lanes (if you do agree with him, I’d wager that you ride a road bike and that you are probably riding it fairly quickly) it’s hard to defend the way he goes about making his arguments.

Anne Lusk tells a story that is instructive.

She got her start in transportation planning by building the nation’s first recreational bike path in Stowe, Vermont in 1981. Despite having a master’s in historic preservation, the bike path was so popular that she found her experience was in demand and she began to give lectures across the country about how to design these recreational paths. And so it was in this capacity that she found herself sharing a panel about cycling infrastructure with John Forester at a conference in Montreal.

Anne says that Forester told her he would like to be able to speak second, in order to rebut her presentation, but since the schedule had her listed second, she stood her ground and kept the order as-advertised. “So John started off not being happy,” says Anne.

“‘Possibly DeLong had such strong dislike for Forester, but Forester merely considered DeLong to be an engineer of low competence.’”

“While he was speaking I knew I was in trouble, because I could see the people in the front row were nodding at everything John said,” she says, recalling that his presentation was all about how bikes should never be separated from traffic, even by a painted bike lane. Anne then put up her slides: slides showing children riding on Block Island with no helmets in bathing suits and bare feet. “They would gasp,” she recalls.

She says she couldn’t see John from where she was presenting, but I got the sense that she believed John was leading this crowd of his disciples with his facial expressions.

“I realized I was being heckled… that I was being booed. It was ‘you don’t know what you’re talking about. We know better than you.’” She says she nearly broke into tears in the front of the crowd, and that this experience is what drove her to get her PhD, in order to use statistics to rebut the arguments that John was making.

John doesn’t hesitate to call people who disagree with him ignorant, or incompetent. He engages aggressively online, either on his own bare-bones website, or in the comment section of articles that he disagrees with. He extensively rebuts authors who take him on. (including my favorite correction, inexplicably written in the third person, to the claim in an article that John and another cycling advocate disliked each other: “Possibly DeLong had such strong dislike for Forester, but Forester merely considered DeLong to be an engineer of low competence.”)

So perhaps it’s no surprise that he has alienated almost all of his potential allies in the cycling advocacy community.

Cycling Advocacy Has Moved On

At this point, Vehicular Cycling is nearly a fully marginalized idea. John and his disciples are barely part of the conversation among advocates for cycling as transportation. This became clear this last fall at the International Cycling Safety Conference that was held this past fall at the University of California Davis. (A tweet-storm account of this conference was actually the first time that I ever even heard John Forester’s name)

“Two of the three plenaries basically were — and I hate to use the word — calling him out,” explains Tara Goddard, the author of that tweet-storm and a professor of Urban Planning at Texas A&M University, “It wasn’t just like, ‘hey we’re attacking this approach,’ but it’s very much 'this person.'”

Tara says that John was given a chance to respond to these critiques from the audience; a kind of live rebuttal of the sort that he typically lodges on his website.

“It really just kind of felt like 300 to 1,” says Tara, “That late-night tweet-storm was me kind of wrestling with that, but ending on a sense of relief and hope because the whole profession is shifting this way. And so I came away with a lot of hope, but still kind of feeling a little bit sad and uncomfortable with how it all went down.”

John is unrepentant in the face of this sea change. “Look, America’s got itself into a terrible tangle. What they aim to do, cannot be done,” he says. He maintains that the America will never build the type of cycling infrastructure that has been built in the Netherlands that American cycling advocates like to push for in our cities. He continues to see his legacy in heroic terms. “I’ve kept vehicular cycling, in other words -- obeying the rules of the road — alive when otherwise it would have been killed.”

But it would seem that at least within the community of professional advocates, a changing of the guard is nearly complete.

Outside/In was produced this week by:

Outside/In was produced this week by Sam Evans-Brown with help from: Hannah McCarthy, Erika Janik, Taylor Quimby, Justine Paradis, and Jimmy Gutierrez.

Special thanks to Bill Schultheiss, Jeff Rosenblum, and Kari Watkins

Music from this week’s episode came from Komiku, Jason Leonard, Blue Dot Sessions, Podington Bear, and Ari de Niro

Our theme music is by Breakmaster Cylinder.

If you’ve got a question for our Ask Sam hotline, give us a call! We’re always looking for rabbit holes to dive down into. Leave us a voicemail at: 1-844-GO-OTTER (844-466-8837). Don’t forget to leave a number so we can call you back.