Life on the Edge of the Olympics

When you watch the Olympics, you think you’re watching the best in the world competing at the pinnacle of their fitness.

And while that is often true when it comes to America’s very best, when you start to get farther down the list, choosing which athletes deserve a ticket to the Olympics gets much more difficult… much more subjective.

And it’s often those margin calls, those athletes on the bubble, who have some of the most inspiring stories to tell. Today, the story of Jennie Bender.

This story first aired on Only a Game

Jennie Bender grew up in Vermont in a family that was not into cross-country skiing. For her first race, in seventh grade, she showed up dressed for a cold day of sitting on chair lifts.

"I remember being at the start line in snow pants and a big, old turtle neck," she says. "Way overdressed next to my fellow competitors on the East Coast, who grew up with Nordic skier parents, and they’ve been racing in spandex since they were 4. I’ve got a picture from that time. And oh, man, it’s embarrassing."

But she was good. From 14 years old on, she was part of the development pipeline for Olympic skiers. She qualified for junior national championships and then junior world championships. She got a scholarship to ski at the University of Vermont. This was when host Sam Evans-Brown met Jennie. He was racing in the Eastern collegiate circuit at the same time. But Jennie raced fast enough to be an NCAA All-American.

After college, she felt like she could compete on a larger stage. So she started looking around for an elite development team that would help her get there and landed at one in Minneapolis.

"It was a really strong team, and there were times at nationals when we swept the podium," she says.

In 2012, Jennie finished third in two races at U.S. National Championships.

She was a powerhouse. In a sport where results are often inconsistent because of differences in technique or course profiles or wax performance, Jennie was top 10 in almost every race she entered that season.

Disease Strikes

She was performing at or near the same level as the women who are now on the U.S. Ski Team.

But then came that summer.

"A skier is created in the summer," Jennie says.

Jennie was at a training camp with her teammates in northern Wisconsin, roller skiing, lifting weights and running in the woods.

"And so I was always the one who — many times the only one -- on our team who would, like, spray myself with DEET," she says. "I was, like, 'I don’t care if I get DEET poisoning. I don’t want a tick on me.'"

But, sure enough, despite all the bug spray, the last week of the training camp Jennie was feeling off. She was struggling to do her workouts.

"I could not do these easy running intervals," she says. "And I was, like, 'Oh, this is bad. What is going on?'"

She went to a clinic, got tested and was told she had Lyme disease. Recovery can take a long time. But that wasn’t all.

"And an hour later that day, I got a call back from the clinic," Jennie says. "And they said, 'Um, Jennie, actually you also have Mono.' And I was just, like ... I was overwhelmed."

Jennie was put on antibiotics and told to rest.

"Resting is like prison. It’s, like, the worst," she says. "You’re, like, 'No!' Especially mid-season. I was feeling really good and really fit. And I couldn’t even really go for a walk. I would go to the end of the driveway, and I would turn around and walk back and just feel drained. And I remember I wasn't allowed out in the sun because of how strong the antibiotics were I was on. I was on a month of antibiotics. I remember sitting in the living room in the dark during the day, and I felt like I was melting into the couch."

Skiers Are Created In The Summer

This was where Jennie’s story and those of her teammates diverge.

The fastest racers from the United States, the U.S. Ski Team, spend their whole winter in Europe, racing the World Cup. The domestic racing circuit, where Jennie had been killing it, is kind of like the training grounds for racing in Europe.

Now, those women from the Minneapolis team she’d joined on the podium at national championships? One was Caitlin Gregg, who would go on to win a bronze at the 2015 World Championships. And the other was Jessie Diggins, who just won gold as part of a historic Olympic relay team at the games in Pyeongchang.

Remember, skiers are created in the summer, and Jennie had spent the summer of 2013 melting into the couch and stress-baking. She did manage to start training again in the fall, but when January rolled around, her fitness was only so-so. But still, she showed up at U.S. national championships, the big stage for skiers who haven’t qualified to go ski the World Cup in Europe.

"I remember making it into the A final and just being, like, 'I don't know if I can do this. I am so exhausted.'

“Really, an athlete will tell you the cliche of, ‘It’s about the journey, not the destination.’ Which is very true. And it gets to a point when you’re in it so deep and you’re, like, ‘No, I want that damn destination. I deserve that destination.’”

"The course fit my strengths and I raced very tactically. And I out-sprinted a few girls at the end, and I won my first national sprint championship," Jennie says. "And I bawled afterward, because, like, I was able to do that after all that I just went through.

"And I’m, like, tearing up thinking back on that feeling. Because that result really saved me in a lot of ways."

Ups and downs would become the theme of Jennie’s career. In 2013, she threw out her back — herniated a disk.

"And I remember having to actually sit on the ground to get my roller skis on because I couldn’t bend over to put them on," she says.

Even so, that year she qualified to go to Europe for the World Cups that came after Sochi — her chance to prove herself with the best in the world and race with the U.S. team. But ...

"A lot of them came back from Sochi with a really bad sickness, kind of the Sochi flu," Jennie says. "And I got sick a couple of days later, and that was that trip."

Trying To Have Fun Again

Over the next few years, Jennie was racing very hot and cold. She wasn’t having fun anymore. She was so wound up about her results that she was making mistakes, crashing.

Whenever she made it to the international scene, she wasn’t having the results she wanted.

"Really, an athlete will tell you the cliche of, 'It’s about the journey, not the destination.' Which is very true," Jennie says. "And it gets to a point when you’re in it so deep and you’re, like, 'No, I want that damn destination. I deserve that destination.' It doesn’t help. I’ll say it doesn’t help."

Jennie always felt a step behind, a step below, as if her whole career she’d been playing catch-up. She just was never able to string together enough good finishes to get to and stay at that top international level.

Last year, Jennie was finally starting to feel like her old self again. She was once again winning or landing in the top 10 of almost every race she entered. She won a sprint at U.S. nationals and was ranked as the best sprinter in the country for the fourth year in a row.

But the U.S. team is currently loaded with good sprinters. And the rules were changed so that to earn a spot on the World Cup, a domestic racer has to do well in longer races, too. So once again, Jennie was passed over.

"So I was in Bozeman, [Montana,] last February — I was kind of bummed," she says. "I was trying to find my happy again."

She decided to go play a game of pick-up hockey. Have some fun.

"Of course no one's wearing a helmet. And someone just decides to slap shot the puck down the ice, and it clocked me in the side of the head," Jennie says. "Everyone was, like ... 'Oh, s---.'"

Jenny got five staples in her head and a serious concussion.

“I was just, like, this shell of a human.”

But even so, racers have to race. Every so often, Canada gets to host a World Cup, and when they do, the U.S. gets extra start spots. And Jennie was on track to qualify for one. She asked if she could skip the final domestic qualifier, but was told no dice. And she knew that getting a start in Canada would help her to get back over to the European World Cups and, maybe, to Pyeongchang. So she lined up at the start.

"I was standing there with my skis watching my start time tick down, and I was, like, 'No, I have to,'" Jennie says. "'Like, I have to. I don’t care if I get brain damage. I have to race this race.' "

She barely did well enough to keep her spot. But she says during the World Cup races, she felt like she was just floating along.

"Like, this was a huge event. I should feel something." she says. "I was, like, 'I feel nothing.' I was just, like, this shell of a human."

Olympic Selection

Jennie stopped to re-evaluate. The Olympic team for Pyeongchang would be selected in less than a year, and her prospects weren’t looking good. The first measuring stick the U.S. team uses is World Cup results. But if you’re not on the U.S. Ski Team, it’s hard to get the World Cup starts you need to make it.

Criterion No. 2 is coaches’ discretion. For this story, I spoke to a half-dozen cross-country skiers who were on the bubble for Pyeongchang, and dissatisfaction with the lack of transparency in how those decisions on discretion were made was the uniting theme in those conversations.

So Jennie says she asked the coaches how they would use it.

"They’re, like, 'You know, we’re really just looking for standout performances. We’re not just going to bring people to bring people, " Jennie says.

Jennie was thinking, only four athletes can start at each race in the Olympics. And the U.S. team already has at least five women who were capable of being in the top 30 in the world on any given day, and she seriously doubted she could be faster than them.

So why would they bring a domestic sprinter? They don’t even need any alternates.

"They just don’t need it. It doesn’t make sense," she says.

The Switch

Jennie decided she had no chance at Pyeongchang in cross-country and decided to switch sports.

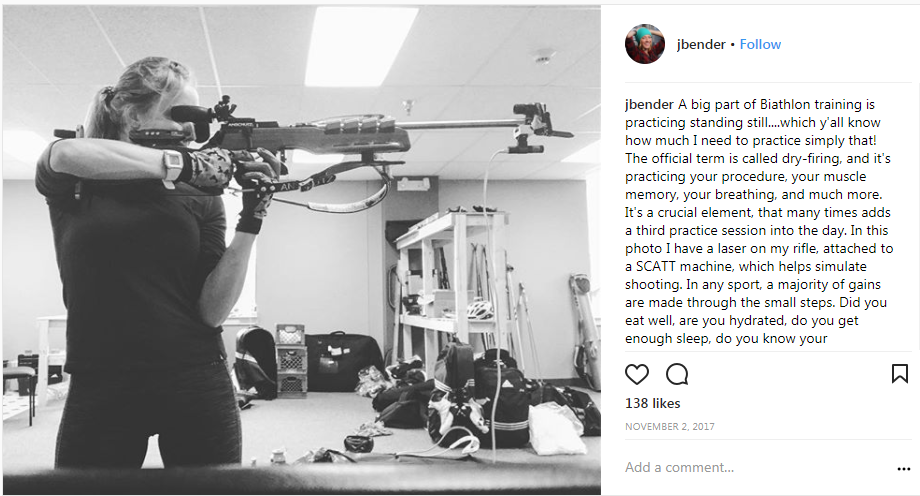

As many cross-country skiers do, she switched to biathlon -- that’s skiing and shooting.

"Because, I was, like, 'I really want to make this Olympic goal, the biathlon criteria is clear, they have trials, so, like, who knows,'" she says. "'Maybe I can pull this off. I don’t know.'"

Considering that the common wisdom is that it takes three years to learn how to shoot, Jennie did pretty well. She qualified for some lower-level competitions in Europe, but not the World Cup and not the Olympics.

"I learned now, like, wow, biathlon is really hard," she says. "Like, damn."

And it was while she was over in Europe doing biathlon races, that she heard the news. The Olympic team had been announced, and one of the skiers was the current leader of the domestic sprint rankings, a slot that Jennie had been holding consistently for the last four years and was told would not be good enough to get her to Pyeongchang.

"And I broke," she says. "I broke mentally, I broke physically. I was, like, 'How is this possible?' I felt, kind of, deceived and lied to. And I bawled. Sometimes there are things that make you turn inside out."

Moving Goal Posts

"It can be a heartbreaking time for some athletes," says Luke Bodensteiner, chief of sport for the U.S. Ski and Snowboard Team. "They’ve put a lot into it, and when they don't make it, it can definitely be a challenge."

The coaches who selected this years’ Olympic squad weren’t willing to be interviewed. Sam knows some of them, too. One coached team New England when he raced at junior national championships.

But Bodensteiner is a step above them. He called to talk from Pyeongchang.

This can get pretty technical, pretty quick. But the ski team says they got more spots for Olympic skiers than they anticipated — 20 racers instead of 18.

Since only four men and four women can start each race, they certainly didn’t need all of these spots. But if they aren’t filled, they are allocated back to other nations, which is against U.S. Olympic Committee policy.

"And that gives us an opportunity to enter more athletes in the Olympics than we have before," Bodensteiner says.

So to fill these two surprise, extra spots, they decided to just go down their ranking list and take the next skiers — and because the next skier happened to be a sprinter, they used discretion to overrule their stated position of only bringing five sprinters.

Jennie’s decision to switch to biathlon was a rational one, based on all of the information she had at hand.

But because discretion means coaches can change their minds at the last minute, that rational decision now looks like the wrong one

"I don’t want to sound like some bitter athlete who didn’t make it — I’m trying to speak up so that this doesn’t happen in the future," she says. "Suddenly this life goal that I’ve had was right there, and the finish line was moved on me."

To be clear, we’re talking about spots for the alternates. They’re the athletes who go over, march in the opening ceremonies, hang out for a few days in case someone gets sick or injured and then go home. If you’re the U.S. Ski Team, worried about winning Olympic medals, the stakes here feel pretty low.

But when you’ve devoted your entire life to an obscure sport, hoping that in one of those moments every four years that the world turns its attention to what you do you’ll get to be on that stage, it feels pretty important. And it feels pretty personal.

Outside/In was produced this week by:

Outside/In was produced this week by Taylor Quimby and Sam Evans-Brown with help from: Hannah McCarthy, Jimmy Gutierrez and Justine Paradis.

Erika Janik is our Executive Producer.

Additional editing from the folks at WBUR’s Only A Game, where this story first aired.

Special thanks to all of the people in the Nordic community who helped Sam report this story.

Music from this week’s episode came from Podington Bear and Blue Dot Sessions.

Our theme music is by Breakmaster Cylinder.

If you’ve got a question for our "Ask Sam" hotline, give us a call! We’re always looking for rabbit holes to dive down into. Leave us a voicemail at: 1-844-GO-OTTER (844-466-8837). Don’t forget to leave a number so we can call you back.