WTF is TFC?

When you walk a trail in the woods, have you ever wondered, how did this get here? Who carved this path? Was this stone staircase always like this? Nope. Chances are a team of hardscrabble men and women worked tirelessly to make sure the paths you follow blend right into the landscape. In this story, we find out why one such trail crew, known as the 'TFC', is the stuff of legend.

“People think these staircases occur naturally,” says Nova.

During the rest of the year Nova is known as Alex Milde. Alex is a clean-cut student at Cornell and a member of its varsity rowing team. But out here, in the wilderness of the White Mountains, he’s the leader of a trail crew and he goes by his woods name: Nova.

“We’ve had people do that. They’ve been walking down our work, talking to their kid, and we’re rolling around in the dirt, clearly putting in a staircase, and they’re like: ‘Yes, honey, these steps were put here by God.’” But they weren’t. They were put there by a crew of people -- mostly college students, working mainly with hand tools -- who labor in obscurity all summer long.

Officially, this is the Appalachian Mountain Club’s professional White Mountain trail crew. Unofficially, it's known as: the TFC.

“It came around in the '70s sometime. It stands for Trail Fucking Crew,” explains Aesop, a second-year member of the TFC, who declines to provide his real name, “We like to say, if your grandma asks what it stands for, you say Trail Fixing Crew.”

The History of AMC's Trail Crew

AMC’s White Mountain trail crew has been around for a long time. In the 1800s, hiking trails were largely cut by the owners of inns and hotels in the White Mountains. In the early 20th century some of the area’s more dedicated hikers, often faculty members of the region’s universities, started to connect these trails. The result was a trail network that was too big to be maintained by volunteer labor alone.

In 1919, the Appalachian Mountain Club formed its first professional trail crew, led by former New Hampshire Governor Sherman Adams, who was fresh out of boot camp and ran the crew accordingly. “He had a reputation,” says Bob Watts who served on the crew from 1952 to 1955 and now serves as the crew's unofficial historian. Watts says Adams once hiked from Littleton to Hanover in something like 43 hours.

1924 Crew at the Flume Gorge

L to R: Harland P. Sisk 1923-26(TM), Leonard B. Beach 1923-25, William J. Henrich 1924-27(TM), William L. Starr 1922-25(TM), Frederick Fish 1923-25, Harold D. Miller 1920-23(TM) & 24(TM), Dana C. Backus 1923, 24 & 26.

That superhuman trek was somewhere in the neighborhood of seventy miles, and Adams did it without Gore-Tex® gear, lightweight boots, or a CamelBak®. The culture that Adams created on the trail crew--hard living, hard working, hard charging--remains today. And in the intervening years, the crew has cultivated a mystique that surrounds them still.

Why is the TFC so legendary?

Pure physicality

Crew members are expected to do “patrols” for two to three weeks each summer. "Patrols" involve hiking between eight to twenty-two miles a day, clearing every fallen tree from the trail, and a year’s worth of accumulated leaves and dirt out of every water bar.

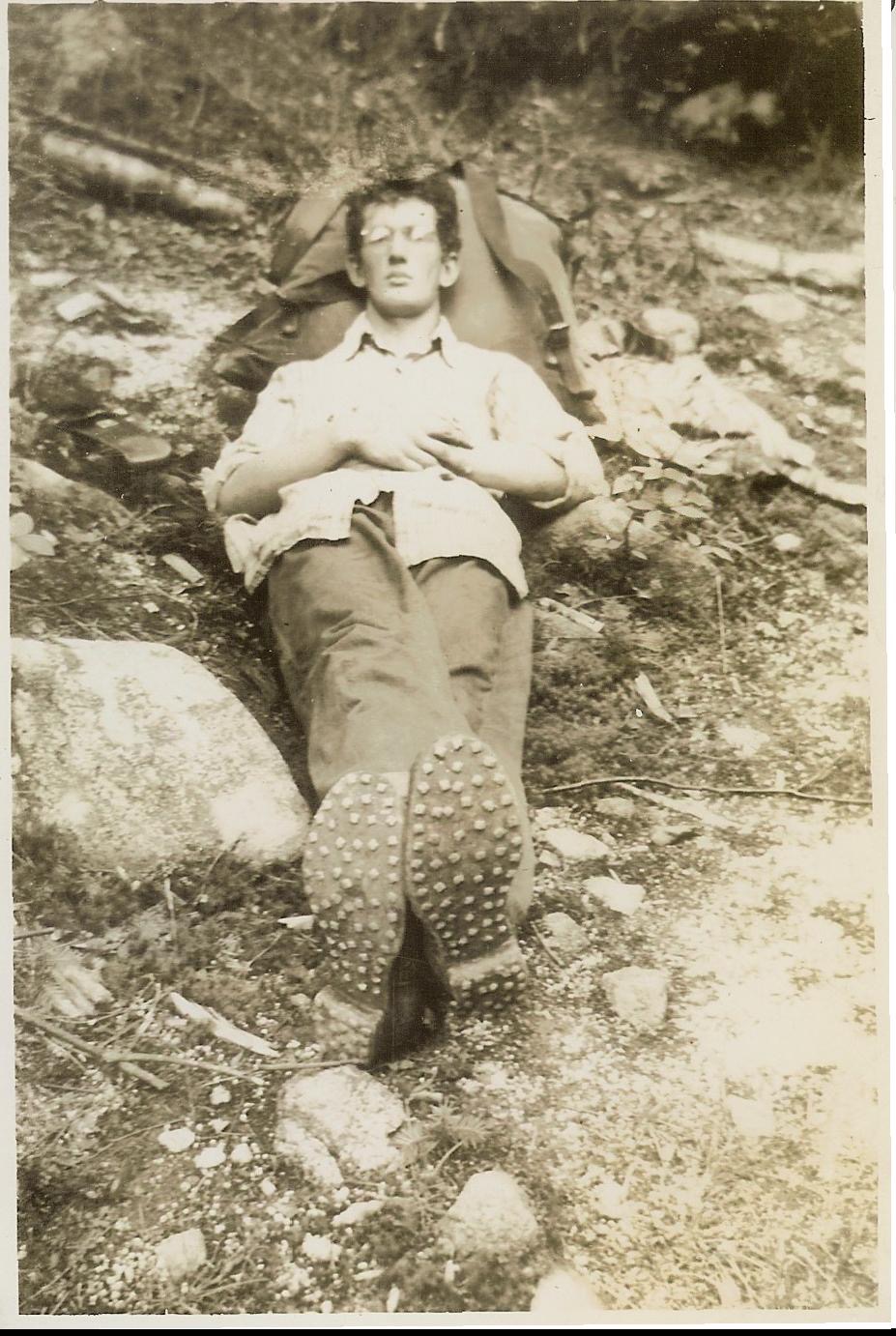

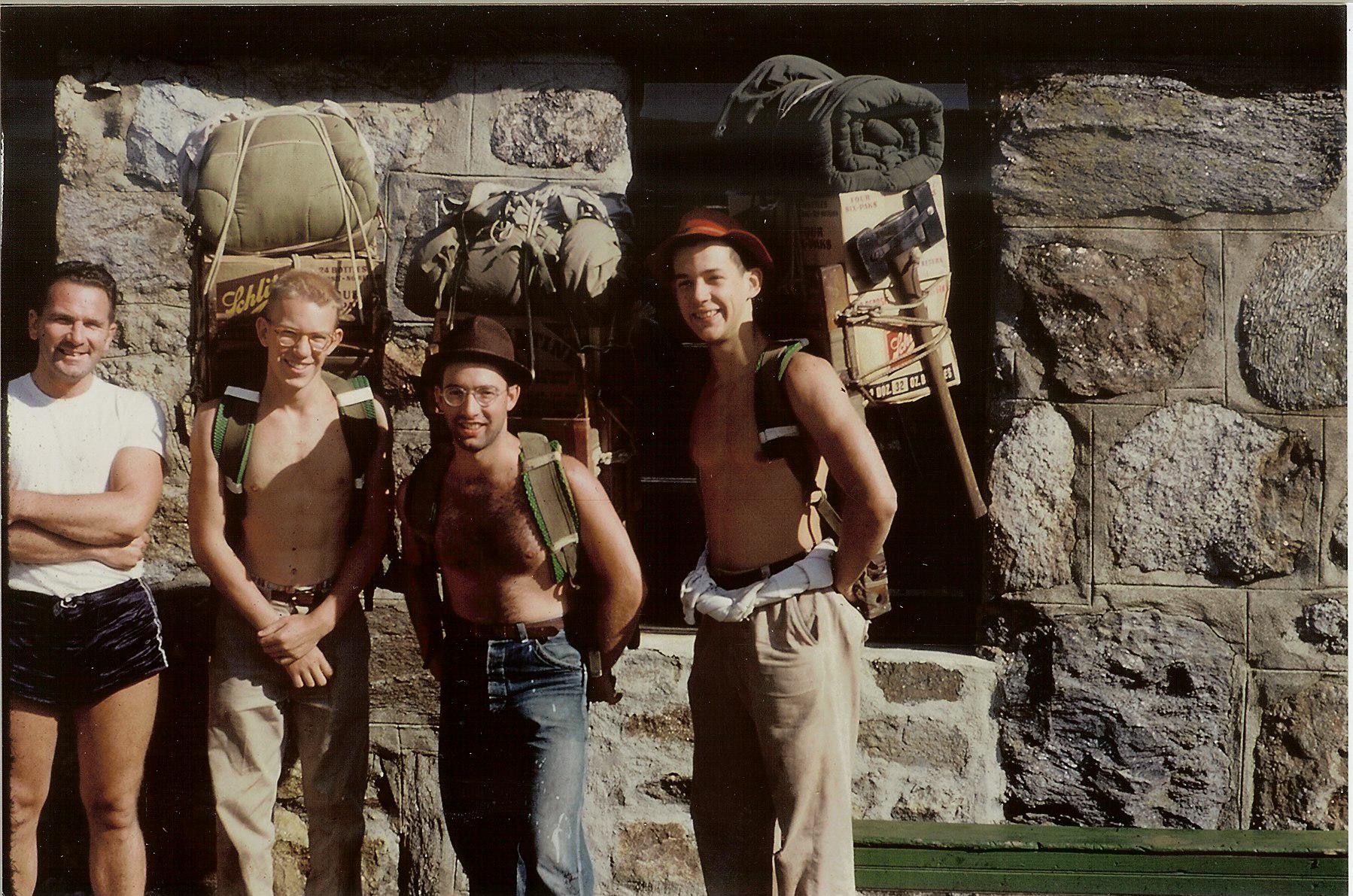

Once patrolling is done, the crew then gets to work on projects. In order to reach the project site, often set deep in the woods, they must pack and carry a week's worth of equipment and food. Their backpacks, which are technically pack boards, usually weigh more than 100 pounds. The TFC boasts that particularly burly crew members will carry 200+ pound loads. There's even a story of an unfortunate crew member who became momentarily trapped under river water after being toppled by the weight of his packboard.

These brutal workdays are accompanied by some equally punishing days off. Bob Watts reminisced about an impressive, but perhaps ill-advised, hike that he and his crew mate embarked on one summer. It took them 27 miles to the next project site and over Mount Washington (one of the most inhospitable peaks in the country) in the middle of the night. Every year, crew members take part in the fabled, 49-mile “hut traverse”.

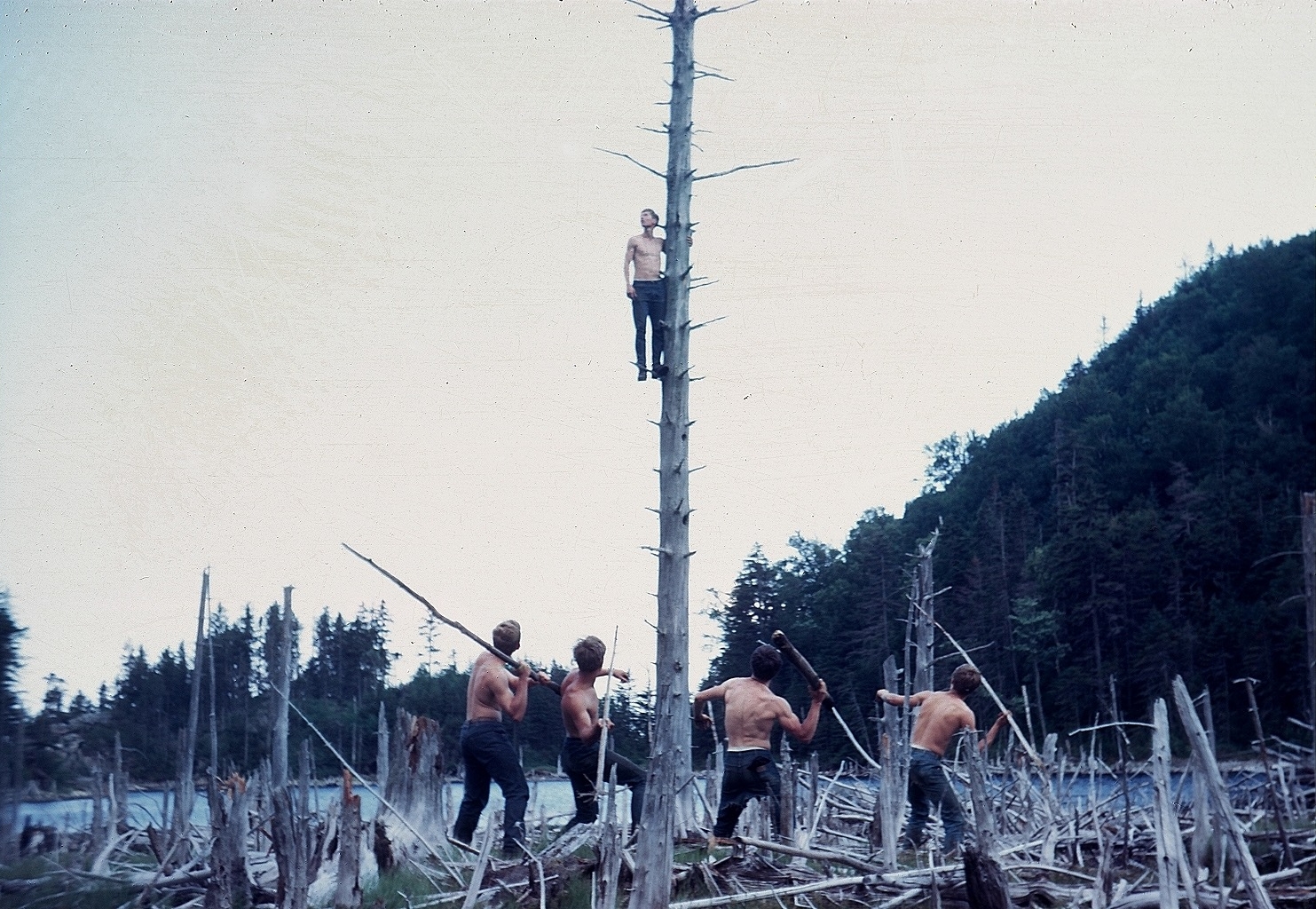

Shenanigans

The trail crew is legendary for being composed of spirited college kids with a penchant for pranks. The most notorious example went down in the '50s when some trail crew members caught wind that President Eisenhower was coming to visit New Hampshire. They decided to put a goatee on one of the state's more notable icons, the Old Man of the Mountain. To do this, they managed to tie some bushes to his rocky chin, which was located forty feet below a cliff edge; all of this just to give him a funny little beard. “So these guys really, for almost a half a century went into hiding and never would admit their participation in this shenanigan,” says Watts.

Ben English, another crew member from the '50s, remembers the time he and his crew mates constructed an over-sized birds nest with sticks and moss. They hard-boiled some eggs, drew spots on them with a magic marker, and tossed them into the faux-nest. When curious hikers passed by and asked about the nest, they responded, “Why, that’s the nest of the alpine duck.”

This tomfoolery is harmless, but I’m also fairly certain they are some of the more PG stories. If you asked me to guess, the most legendary tales, the kind that attract new crew members from college campuses all around the country, don’t get told to a reporter carrying a microphone.

The Look

To match the mystique they’ve cultivated over the years, the crew has adopted a certain style. Members of the crew don’t look like earth-loving hippies, or tech-fabric wearing ultra-athletes. They’re more like filthy, muscled punk rockers, wearing heavy work boots and stained t-shirts. Many of them sport mohawks, which they say optimizes their aerodynamics for hiking fast.

“My theory is it’s also a radiator,” Nova explains, “So shave the hair on the sides so that allows a lot of heat to radiate out and you evaporate, and then you have the vein of hair coming down the center and that condenses the sweat coming off your head and recirculates it.”

Getting grimy is expected; this is pretty much a one shower a week kind of group. John Lamanna, who was on the crew in the '70s, explains the ethos this way: “Any trail crew guy worth his shit, he would rather have mushrooms growing out of his underwear--if in fact he wore underwear--than [...] ever be caught with his axe dull or not ready to go.”

What’s it like to be on the TFC?

Joan Chevalier was the first woman to be on the trail crew back in 1978. She had worked in the huts, but was always envious of the trail crew. “I wasn’t really a people person, per se,” she says. She started in the huts, and eventually became the caretaker of Guyot shelter the summer it was being rebuilt by the the trail crew, so she worked closely with them. Afterwards, the head of the crew invited her to join the team.

“AMC was one of the places where finally...that women and men were equal,” she says. “It didn’t matter, everybody did what they could do and made a contribution.”

Anna Malvin, a current crew member whose woods name is 10-Gauge, agrees, “The only time I really notice I’m a girl is when like, hikers will pass and make [...] sexist comments. Like, ‘Oh, why don’t you get the guys up there to help you and stuff like that.”

But, “it was almost like a fraternity,” says Chevalier. “They just really had a lot of fun, working very very hard and doing amazing things to keep the trails up.”

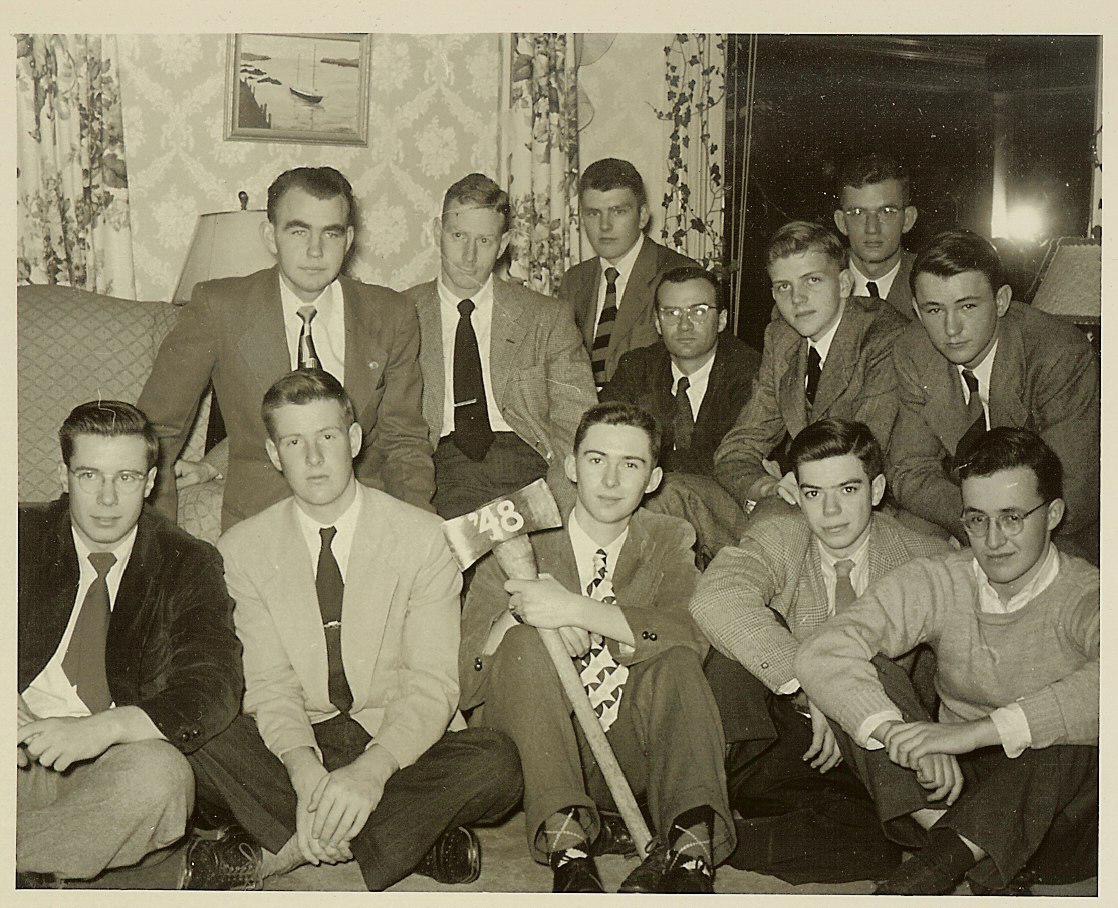

2012 Crew

There are echoes of fraternity culture in the TFC’s traditions.

“You don’t really get hazed,” says Malvin. She points to traditions like delegating more menial chores--like having to carry a week’s worth of trash out of the woods--to first year crew members. And then there was this: “We had to take a test at the beginning, just as a joke. Like ‘what color are this person’s tighty-whitey’s?’ While getting little balls thrown at us,” she says, laughing. “But it’s all in good fun.”

“It is sort of difficult, sometimes, to see the line between what’s hazing and what’s bonding,” says Peenesh Shah, who was on the crew in 2001 and 2002. He says an example is the tradition of always keeping your axe close at hand. Ben English explains this tradition stems from a tendency of porcupines to gnaw through the “salty handles” of the axes. Shah once left his axe on a workbench while eating dinner, and some senior members of the crew took it and hid it from him. "You know I think there’s some element of hazing there, but there’s at least some purpose to that.”

“Ultimately it’s pretty harmless right,” he says, but these traditions create a sense of cohesion. “I don’t think you’d be able to get that quality of work product, or just the amount of labor the crew puts in for the amount they get paid, unless there was some other benefit and that benefit is pride.”

“This trail crew job, this is not something that they just drop in out of the sky and work for a summer in the woods in the White Mountains,” says Ben English. “They might think that way when they plan to get here but they find out quite soon that it's different.”

But when it comes to telling the best stories of fun and fellowship in the woods, the ones that bring in new trail crew members year after year. Ben English and John Lamanna demure.

I ask, “Are these stories too good for radio?”John Lamanna responds “We have to maintain a certain mystique around us. We don’t want the whole friggin’ world knowing how good this is, because they’ll all want to do it.”

So there you have it. If you want to know what it’s really like to be on the TFC--the heavy loads, the long-days, the shenanigans in the woods and the life-long friendships -- you’ll just have to join up yourself.

Historic photos courtesy of Trail Crew Association archives.

**Correction: An earlier version of this article quoted Bob Watts saying Sherman Adams once hiked from Whitefield to Hanover in 43 hours. Watts later amended his statement to say this hike actually was between Littleton and Hanover**

Robert Moor - On Trails

Robert Moor is the author of a book called On Trails. Robert started thinking about trails while walking the Appalachian Trail in 2009, and decided to write about trails generally when he realized that no-one was interested in another story about a middle-class white guy walking the AT.

"[He] began to wonder about the paths that lie beneath our feet: How do they form? Why do some improve over time while others devolve? What makes us follow or strike off on our own? Over the course of the next seven years, Moor traveled the globe, exploring trails of all kinds, from the minuscule to the massive. He learned the tricks of master trail-builders, hunted down long-lost Cherokee trails, and traced the origins of our road networks and the Internet." (Source: robertmoor.com)

Walking the AT does have a profound effect on people, it certainly changed Robert, as you can see from the photo below.

BONUS: It also includes this somewhat upsetting photo of me before-and-after my hike. pic.twitter.com/3MD1GgB27u

— robert moor (@robmoorstuff) August 2, 2016

Outside/In was produced this week by:

Sam Evans-Brown, Logan Shannon, and Cordelia Zars. With help from Maureen McMurray, Taylor Quimby, Molly Donahue, & Jimmy Gutierrez.

Special thanks to former TFC members Kyle Peckham and Natalie Beittel who are assembling a book of stories of people from the crew. Also Barbara Whiton of the Trail Crew Association who helped Sam track down old crew members. Thanks as well to Rob Burbank of the AMC and Cristina Bailey of the National Forest Service for setting up the day out on the trail.

Theme music by Breakmaster Cylinder

Photos of Sam are by Greta Rybus unless otherwise noted.