Anothah Boston Cheat

Ari Ofsevit is a guy from Boston fueled by an intense, nerdy love for sports. The day after running this year’s Boston Marathon, his face was all over the cover of the Boston Globe and on all of the network news channels, but on the internet, people were accusing him of cheating. This is Ari’s story.

The Boston Marathon has a long, well-documented history of cheaters.

Of course, there was that most famous of marathon cheaters, Rosie Ruiz, who hitched a ride on Boston subway 10 miles into the race. But cheaters abound: there’s this armchair investigator who claims to have found at least 47 people who cheated back in 2015 by taking someone else’s bib, or by taking short-cuts in their qualifying marathon. There’s also the thriving online marketplace, where people say they’d be willing to spend as much as $5,000 dollars to get their hands on someone else’s starting number.

And this year, once again, a high profile Boston marathon finish is being called into question.

The racer in question is Ari Ofsevit. And he’s a friend of mine.

After the race, I was very surprised to see Ari was all over the internet.

.@RachelGBowers interviewed Ari @ofsevit & 1 who helped him across #BostonMarathon finish https://t.co/yvvXJJIlno pic.twitter.com/H8PInweTfW

— Boston Globe Sports (@BGlobeSports) April 19, 2016

@BGlobeSports @ofsevit @RachelGBowers This happened right in front of me! pic.twitter.com/VwPS7ps60I

— Brian Mengini Photog (@BMenginiPhotog) April 20, 2016

They carried him to the finish. #support #character #whateverittakes pic.twitter.com/Mv5dwlwhiV

— meb keflezighi (@runmeb) April 18, 2016

Ari Ofsevit recovering @TuftsMedicalCtr two days after running marathon. Carried across finish line. #wcvb pic.twitter.com/7y9MQRjGoK

— Reid Lamberty (@ReidLamberty) April 20, 2016

I was then doubly shocked to learn that beneath every story written about Ari and in a forum of a website called Let’s Run internet commenters were calling for him to be disqualified.

When Runner’s World noticed the online muck that was swriling around Ari’s story whenever it was posted, they stirred the pot, posting a second article about the reaction to the first article, inviting readers to “engage” on the question.

“So, there are people who say you cheated,” I said to Ari, when I interviewed him.

Ari responded with an exasperated snort.

“With cheating you have to have intent,” he said, “People were saying things like, he shouldn’t have accepted the aid from those guys. Well you know, I didn’t have the opportunity to say that because my brain was not functioning.”

Today's episode of Outside/In (which I encourage you to listen to, instead of reading… I promise, it’s better) is the story of my friend Ari, his fifteen minutes of fame, and the bigger question: what’s a race like the Boston Marathon for?

What Happened?

If you want to hear this story straight from the horse’s mouth, with an impressive dose of profanity mixed in, you can read Ari’s account of why he thinks he collapsed just before the finish line of the race. What’s below is my abridged account.

His preparation for the marathon the day before was pretty reasonable - despite making a transcontinental flight the morning before the race. Ari hydrated, he slept in his own bed, and he woke up before his alarm.

And that day, Marathon Monday, was gorgeous weather, 65 degrees and sunny. (Though Ari, who hates running when it’s hot, calls it “sneaky warm”.)

The first 17 miles Ari felt great and was on track to beat 3 hours. He says he was drinking every water stop. But as the race wears on he started to slow down, though he said it was nothing unusual.

“Most people are going to feel lousy on those hills,” he said.

He’s slowing down: from 6 and half minute mile pace, to 7 minute mile pace… to mile 26 when he’s up to nearly an 8 minute mile.

But he turned the corner onto Boylston street, and then end was in sight.

“I remember thinking, “Alright legs, go,” Ari said. That thought was the last thing he remembers before waking up in the intensive care unit four hours later.

Did he finish?

Ari got to within 200 feet of the finishing line before collapsing with a body temperature of 108.8 degrees. At this temperature, doctors told him he had a 30-minute clock ticking toward organ failure and brain injury.

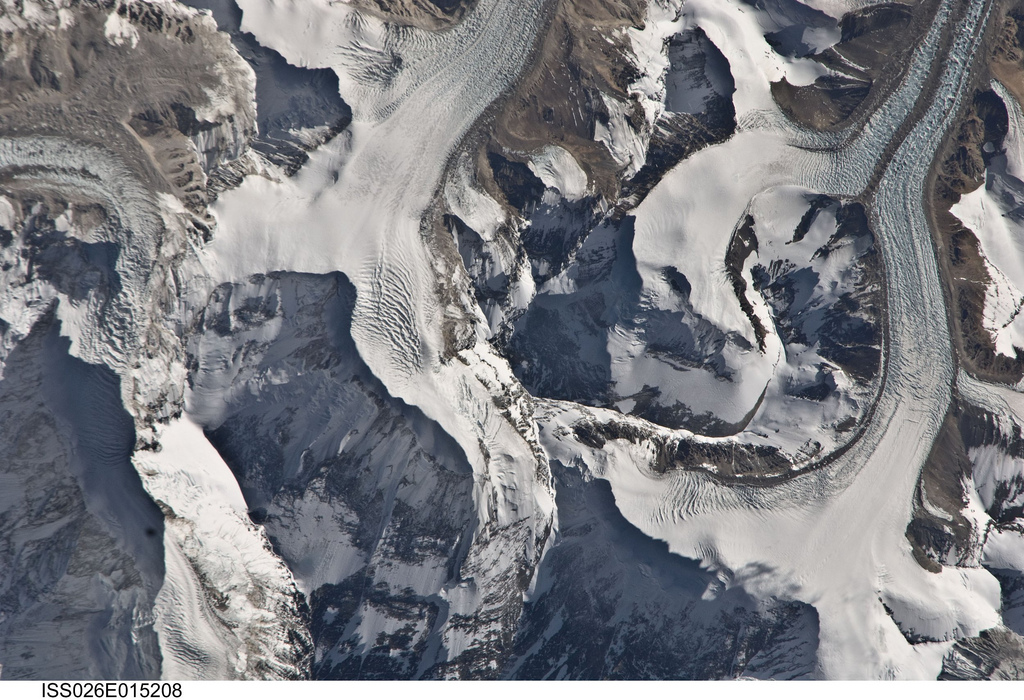

ari did pretty well... right up until the very end of the race

Two runners helped him across the finish line. And first responders dumped him into a tub of ice. This actually led to an over-correction, and when they sent him off to the hospital he was actually hypothermic: his body temperature had dropped to 84 degrees.

Ari didn’t break the 3-hour mark, but he did get a time: a very respectable 3 hours and 3 minutes. You can find his name, and his time on the results. He finished in 1848th place - and like all finishers, he got a medal.

Once his story started to hit the media, first on the cover of the Boston Globe, and then later on the network TV channels, certain parts of the running community started grousing.

“To me, it would have been considered, he should have been a DNF,” Jay Curry told me. DNF is runner-speak for “Did Not Finish”.

Curry is an an OR nurse, a cyclist and a triathlete. He’s never done the Boston Marathon, but he has done ironman triathlons: that’s where you have to run a marathon after swimming 2.4 miles and biking 112. I found him through a Facebook comment he left underneath one of the articles about Ari.

“It kind of takes away from the sport, if anybody can just pick him up and carry him across the line or I could jump on a bus and say, Jeez, I’m kinda tired right now, I’ve got two miles to go I’ll just call a taxi and take a taxi to the finish line and be considered a finisher.”

Jay says he has no ill-will toward Ari, and doesn’t think he deliberately cheated. But he’s steadfast. Ari did not finish. And Jay’s not alone. For every 10 people who celebrate his finish as a story about good sportsmanship and community - there are one or two that say, nice story, but he should be disqualified.

Albert Shank a Spanish teacher and marathoner from Arizona is another.

“You’re toeing the line running the same exact course at the same time as these elite runners from Kenya, and Ethiopia, and the United States and all over the world, and I think you should be subjected to the same rules as they are,” Shank told me in a phone interview.

When it comes to this question of whether he deserves to be considered a finisher, there’s a legitimate point being made. If Ari had been in first place, he definitely would have been disqualified. This actually happened in the Olympic marathon in 1908. Dorando Pietri, an Italian, had to be helped to his feet by the course umpires when he collapsed five times in the last 400 meters. The second place finisher -- an American -- protested, and Pietri lost his gold medal.

Ari has done a lot of races... a lot of races.

What's a race for, anyway?

But there’s a big difference between an Olympic athlete , and Ari Ofsevit. Hell, there’s a big difference between the front of the Boston Marathon and Ari Ofsevit.

“I understand that there are folks out there in the world that, a rule is a rule is a rule, and I get it… god bless ‘em for feeling that way,” said Dave McGillivray, the race director of the Boston Marathon, one of the people who very well could have disqualified Ari.

The rules are that runners accepting aid from others “may” be disqualified, not that they “shall” be disqualified. Typically, the routine is that another competitor submits a complaint, which the race jury considers. In Ari’s case, there was no complaint… at least no official, not-in-an-internet-comment-section complaint.

“It was a gallant effort, and I feel he earned the medal. Let’s move on,” said McGillivray.

In reality, there are two races going on in Boston, with two different sets of rules. One of those races -- the elite field -- is really only about who is fastest. The other, is mostly just a community building event. One that would be totally ruined if you militantly disqualified thousands of people who did things like take water from someone other than an officially sanctioned water-stop.

Some of the complaints circle around the prestigiousness of the Boston Marathon. It’s really a tough to race qualify for, and so many people register that in 2016 more than 4,500 people who made the official qualifying time still got turned away.

Because he finished, Ari will likely qualify for next year’s marathon and he could be taking a spot from a runner who finished the race on his own two feet.

They carried him to the finish. #support #character #whateverittakes pic.twitter.com/Mv5dwlwhiV

— meb keflezighi (@runmeb) April 18, 2016

Take it up with Meb

So who gets the final word? I’m going to give it to Meb.

Meb Keflezighi -- olympic silver medalist, winner of the 2014 Boston Marathon, and general goodwill ambassador for the sport of long-distance running -- actually tweeted a photo of the guys carrying Ari across the finish. That tweet was above, but here it is again.

You’ll notice, Meb didn’t write #ObviousDQ.