Fantastic Mr. Phillips

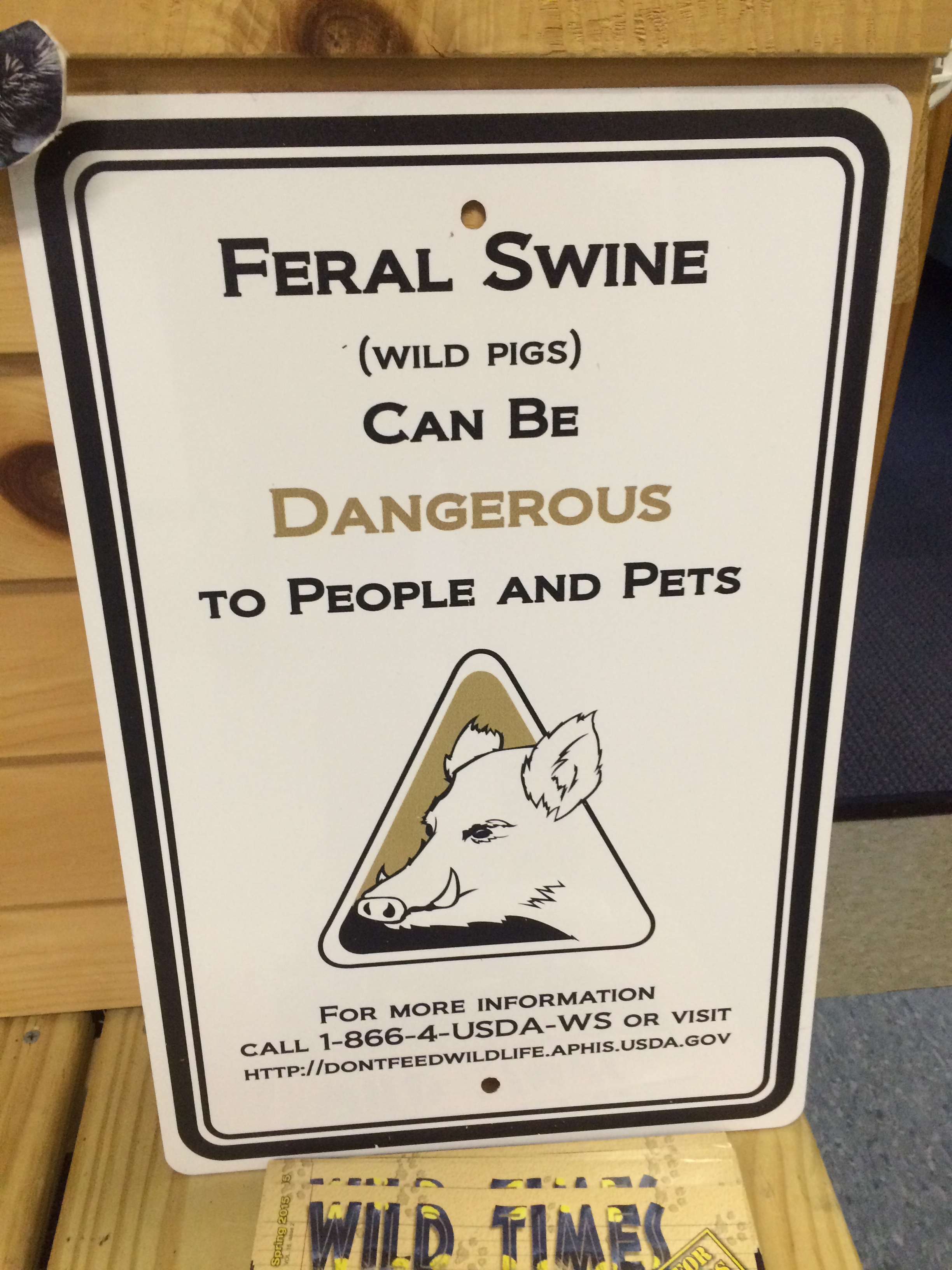

In the late sixties, a soap factory in suburban Illinois discovered one of its outflow pipes had been intentionally clogged by an industrial saboteur. Does environmental damage ever demand radical action? And when does environmental protest cross the line and become eco-terrorism?

In a suburb of Chicago, there is a Dial soap factory.

One day in 1969, a pipe that carried industrial waste out of the plant got clogged and started to back up, causing the factory to shut down. When the employees located the problem they realized the pipe was full of debris that had been mixed with concrete.

By one account, it was as much as seven tons of junk clogging up the works.

Article detailing a second attempt by the Fox at clogging the pipe. | The Aurora Beacon News | march 24th, 1971 | Page 1

Next to the pipe was a sign, which said something along the lines of: “Armour-Dial pollutes our water.” (Back then, Dial was still a subsidiary of the meat-packing company Armour.) The sign was autographed with: “the Fox.” The signature might have been referencing the river that this sludge was polluting—the Fox River—but it came to be known as a pseudonym; a calling card for a mysterious environmental vigilante.

Seven years earlier, the state of Illinois passed a law that was supposed to limit the chemicals that factories like this could dump into rivers and lakes, but Armour-Dial had largely ignored it. Now, somebody was calling them out on it; under the cover of darkness, somebody had come to teach these companies a lesson.

This protest didn’t bankrupt Armour-Dial, but it was just the beginning of a years-long campaign that this anonymous crusader waged against the company. In 1975, six years later, the state of Illinois brought them to court, and told them to clean up their act; the Fox had beaten an industrial giant.

Today, we know who waged that secret campaign. When this all started, he was a high school biology teacher named Jim Phillips.

“He didn’t make a plan to be ‘the Fox’. He didn’t come out and say: 'Here’s what I’m going to do, I’m going to be a crime-fighter, I’m going to be an environmental sage!' or whatever,” says Rob Phillips, one of the Fox’s nephews.

“This is a guy who’s upset,” adds Jim Spring, another nephew. “This is an average American who saw an injustice and went, wait a minute, that’s ridiculous.”

The Fox is Born

Jim Phillips, according to his nieces and nephews, was the fun uncle. He never got married, never had kids, but kids loved him.

“It was such a treat to go spend the night out there on the weekends, and part of that was rambling around at night actually, just looking at stars, looking at nature,” says Nancy Spring-Epley, one of Phillips’ nieces. “We would wander up to probably a couple of miles from the house; we’d go out for hours at a time after dinner.”

This was a time when the waste products of the industrial revolution were starting to get totally out of hand. The year the Fox carried out his first caper was the same year that—being absolutely covered in oil slicks—the Cuyahoga river in Ohio caught on fire. This was the same time that Maine’s Androscoggin River was so polluted that vapors coming off it, supposedly caused the paint to peel off the sides of houses that faced it, inspiring Senator Ed Muskie to champion the Clean Water Act. It was the apex of industrial pollution in America.

A few states started to try to clean things up, but in Jim Phillips’ eyes, progress was too slow.

“Nobody seemed to care, well, he cared. And then he started demonstrating just how much he cared,” says Rob, “It cost people a lot of money when they found out just how much he cared.”

The stunts began to capture the attention of the media, starting with one stunt in particular. A few years after the first clogged drain at the Armour-Dial plant, the Fox took aim at the biggest steel producer in the country, which at the time had around 200,000 employees, US Steel.

“He collected together a big jar of the kind of stuff that they were dumping in the river. Just waste!” recalls Sandy Benhart, another niece. The Fox told newspaper reporters that he collected it from a drain that came directly from a US Steel plant in Gary, Indiana, and that he added some clams and fish for good measure. He also crafted a tiny coffin and laid three dead creatures inside: a perch, a crayfish, and a frog.

The Aurora Beacon News | December 23, 1970 | Page 1

Sandy actually accompanied her uncle on this raid. She says she, her mother, and sister Ginny all went into town on the train. “He preferred to operate legally, but nobody came and paid any attention, so he was absolutely a nervous wreck,” she remembers, “So Ginny and I were his cover.”

While they waited in the lobby, Jim went up to office of the company’s vice president, and declared “I am from the Fox Foundation for Conservation Education, and we have an award for US Steel for their outstanding contributions to our environment.” He then opened up the top of the bottle and dumped its contents on the lobby’s white shag carpet.

The stunt grabbed headlines all across the country, and the Fox had cemented his place in history.

A Widely Held Secret

The stunts kept coming. He took to hanging big signs in public spaces, shaming polluters: one was on a famous Picasso statue in downtown Chicago, another was a banner on a big railroad bridge. He put caps on industrial chimneys. He would hang dead skunks in the offices of CEOs.

After these raids, Jim Phillips would call the press. He would talk to them using a harmonizer to disguise his voice. He even spoke with television journalists.

These reporters kept his confidence. His campaign was covered by a nationally syndicated columnist, Mike Royko, who was very sympathetic to the cause. Royko wrote that he would receive angry phone calls from executives at the affected companies who would quote: “sputter and threaten lawsuits and demand to know who this dangerous character was.”

Later, Phillips got a job with the local branch of the EPA, which then meant he would sometimes be called as an official source by the same reporters who he had called to notify about a raid. You can still find articles where he is quoted twice, once as the Fox, and then later as a “Kane County environmental officer.” It’s unclear if some of these reporters knew what they were doing, or if this was simply serendipity.

But Royko never told. Nor did anybody for that matter.

“There were sometimes where he had to break windows on companies to put a sign in, or throw a skunk juice in there, and he would leave a money order to repair the window.”

For the nieces and nephews, when they were small, they were kept in the dark, but as they got older—usually around age 13—they each found out. “When we were little, I remember I was told it was Dick Young, who was his boss at the EPA in Kane county,” says nephew Jim Spring, “He just lied right to me.”

Jim Spring learned the truth by accident, after his junior high science teacher said they would get to talk to the Fox over a phone link-up, and Spring recognized his uncle’s voice. (As a side note, just think about this for a moment: Phillips was committing criminal acts, and high school teachers were asking him to speak to their classes.)

Article about the Fox in which Jim Phillips, a.k.a. the Fox is quoted. | The Aurora Beacon News | July 27th, 1984 | Page B4

It was in some ways, an open secret: kept widely, but still, somehow, closely. Phillips used to say that if he ever crossed the line, he’d be arrested the next day, because so many people knew who he was. This group included members of the local police department, who would occasionally help him on his raids by leaving notes in a bottle in a certain tree stump, notifying him of where and when security patrols would pass by his targets.

The Fox was not universally adored—you can find letters to the editor in the newspaper on both sides of the issue—but for three whole decades, his secret never found its way into the hands of people who would prosecute him. He was even caught by the police twice, read his rights, but never charged.

“There were sometimes where he had to break windows on companies to put a sign in, or throw a skunk juice in there, and he would leave a money order to repair the window,” says Jim Spring.

After his famous raid on the offices of US Steel, he heard that the odor of the effluent he poured on the carpet had made the secretary feel nauseous, so he sent her flowers.

Over time, the Fox’s raids became lower profile, and he dropped out of the limelight. But Jim Spring and Nancy Spring-Epley still remember the last raid they helped their uncle with, in 1988. They crossed a river, broke a window, and squirted a syringe-full of a chemical used in stink bombs into the headquarters of some small-time polluter.

Once he got back home from the caper, Jim Spring says he was shaking, couldn’t sleep and had to get himself a glass of scotch. “I remember thinking, ‘I’m married, I have a mortgage. There’s no way I can deny any of this.’” He recalls. “This is no longer a fun thing a teenager does with Uncle Jim; this is what adults do to fight corruption.”

But even as the Fox was winding down, others were picking up the baton of radical environmental activism. And some of them had very different ideas about how to get their message across.

Eco-radicals Rising

One night in October of 1998, eight fires erupted all across the ridges and peaks of Vail Mountain Resort. The fires went up one after another: snack-bars, chairlifts, and the largest building—the one that the news helicopters would circle around for hours as it went from a small blaze, to a structure fire, to eventually a smoldering pile of cinders—the Two Elks Lodge.

Immediately, investigators suspected arson, and found a trail of footprints from someone who ran down the mountain, following the path of where each fire was set. They found evidence that the fire had been set using five-gallon buckets full of diesel and gasoline. A few days after the fire, they learned they were right. An anonymous email, sent to a local radio station, said the fire had been set by a group called the Earth Liberation Front. They said the fires were set to protest the ski area’s expansion into an area they claimed was lynx habitat.

But after that, the trail went cold. For years, no arrests were made.

By some accounts the Fox was the first environmentalist who was willing to go outside of the law to try to make his point, but he certainly wasn’t the last. Not long after came Greenpeace, filming their confrontations with whaling ships and nuclear weapons testers. And then there was Edward Abbey’s Novel the Monkey Wrench Gang, in which a team of misfit eco-saboteurs traveled around the west, destroying billboards, disabling bulldozers, and destroying bridges. The book inspired groups like Earth First! (which is always written with an exclamation point, by the way) to start doing things like hammering clandestine metal spikes into trees that would damage loggers’ chainsaws if they tried to cut them down. And if you follow this lineage all the way to the end, or at least what so far has effectively been the end, you find the group that set fire to the lodges in Vail: the Earth Liberation Front.

The ELF had a things in common with terrorist organizations: they operated in cells, which were organized individually, not directed by some top-down central office. They didn’t know who the members of other cells even were. The most active groups were in the Pacific Northwest, and they targeted companies who they believed were doing environmental harm, including meat-packers, timber companies, SUV dealerships, and biotech research labs. They made sure that these buildings were unoccupied, so no one was ever injured, but they caused massive property damage. They watched as timber companies harvested stands of old-growth forest with 500 years old trees, and felt that the action happening through official channels wasn’t working.

“To them, they say this as if somebody were knocking down Notre Dame, just destroying something that’s completely irreplaceable and sacred,” explains Marshall Curry, director of the Oscar-nominated documentary, If A Tree Falls: The Story of the Earth Liberation Front.

The Earth Liberation front succeeded in one way. They got headlines. Those headlines, though might not have been the ones they were hoping for. While the Fox was seen as a vigilante, the ELF were branded Eco-terrorists and virtually every story about them led with this term.

“My understanding is that that was actually a term that was coined by Ron Arnold, who was kind of a spokesman for the extraction industries, and was famously quoted as saying he wanted to destroy the environmental movement,” says Curry. “It’s an incredibly clever term because it rolls off your tongue and it sticks in your ear just like the best marketing campaigns.”

This term may also have stuck because visually, their actions looked a lot like terrorism. Images of multi-million dollar ski lodges in Vail being turned into smoldering holes in the ground, or of Hummers exploding as fires reached the gas tanks, attracted news camera crews like moths around a campfire. Despite the careful avoidance of casualties, the group was perceived as violent extremists.

And this perception undermined their success.

“It’s an incredibly clever term because it rolls off your tongue and it sticks in your ear just like the best marketing campaigns.”

“I spoke to people in Vail who were part of the protest movement against the expansion of the ski resort in Vail. And they told me they had built a really great coalition there of old lady bird watchers and yuppies who wanted to ride their mountain bikes and crunchy old hippies and scientist environmentalists... and that when the fire happened there, suddenly everybody said, ‘oh jeez, I don’t want anything to do with these crazies,’” Curry explains. “Suddenly the coalition completely splintered, the ski resort completely won the PR battle, and it completely undercut their support with the mainstream.”

Compared to the 1960s, when protesters of all kinds were taking to the streets and demanding changes of all sorts, the ELF was operating in the post-9/11 era: the time of the USA PATRIOT Act, and the War on Terror.

The FBI launched "Operation Backfire", where they managed to convince one member of the ELF to turn on his co-conspirators, and then travel the country wearing a wire, and getting them to incriminate themselves on tape. Thirteen men and women were arrested. Many turned state’s witness in exchange for avoiding jail time, but a few did not and were eventually convicted on a charge that included a “terrorism enhancement.”

So, Is this "Terrorism"?

Marshall Curry says the activists he spoke to maintain that their activities are closer to something like the Boston Tea Party, and call it “symbolic property destruction.” But at the same time, the victims of the arson felt differently.

“In their minds, the essence of terrorism is: are you trying to inflict fear on somebody,” says Curry, “They get a call in the middle of the night that suddenly their office or their factory or their life’s work has been burned up, and I have to say that if somebody lit my office on fire, and destroyed the only files of movies that I had been working on and sent a threatening communique, I would say that yes, that I would consider that to be terrorism.”

Terrorism has a legal definition, but it also has an emotional definition. Whenever I’ve told people about the Earth Liberation Fronts actions—arson, spray painting slogans on walls, using splashy media stories to try to get their message out—I watch their faces, and what I see is horror.

We can imagine our homes being burnt to the ground and our way of life being vilified, and that is terrifying. But is it terrorism?

Marshall Curry says the sister of one of the convicted ELF arsonists, who is not at all sympathetic with her brother’s cause, told him something that he will never forget. She says she grew up in Rockaway, in a neighborhood full of cops and firefighters, which was devastated with families that lost their fathers in 9/11.

“She said, ‘I know what terrorism feels like,’” says Curry. She says that to use the same word to describe what Al Qaeda did to those families to describe burning down an empty building, “is just a twisting of that word.”

But a judge disagreed. Based on the law, using ignition devices to light property on fire to convey an ideological message, that’s terrorism.

Both the Fox and the members of ELF were engaging in illegal activity. But these two stories feel very different. Somewhere between the Fox pouring caustic chemicals on the carpet of the corporate offices of a major manufacturer, or breaking a window to squirt smelly chemicals into a polluter’s building—somewhere between that and burning down a building, it seems that a line is crossed.

After this line society says: “That’s not a reasonable way of making your point.”

We can ask ourselves, if the Fox were to come back today, what would his community think? The same low-level law-breaking that was accepted in the era of the anti-Vietnam protests and the Civil Rights movement, might have been seen very differently in the early 2000s, right after 9/11. Maybe in post 9/11 America, his acts of small-scale industrial sabotage and vandalism would be seen as unpatriotic.

The beacon News | May 4th, 2006 | D2

Jim Phillips’ had diabetes, and died in 2001 at age 70. It was only after his death that it became public that he was the Fox. Big newspapers all around the country, including the Chicago Tribune, but also the New York Times, and the Los Angeles Times ran an obituary, laying out his whole story. Once the secret was out, far from repudiating him, the community thanked him. They put a plaque with his symbol in a local riverside park.

There’s a question that we’ve been kind of dancing around, here.

Dumping waste into a river has an immediate, visible effect that can inspire outrage in a community. Meanwhile, the impacts of something like global warming are slow and harder to see. But on the other hand, for the first time those impacts are now on our doorstep.

Given the events of recent weeks—references to climate change getting scrubbed from the EPA’s website, government employees creating alternate twitter handles to broadcast facts about climate change, and the new administration stepping aside to clear the way for the Keystone and Dakota Access pipelines—it seems fairly clear that the US government isn’t about to do anything about climate change. So, what will environmentalists do about it?

As the possibility for action through official channels is beginning to close, we might be on the verge of seeing a whole new wave of copycats, or copy-foxes, as it were.

How will society receive them? I guess we’ll find out.

The Aurora Beacon News | June 13th, 1976 | Page 17

The Aurora Beacon News | January 22, 1980 | Page A5

Aurora Beacon News | April 9th, 1971 | Page 1

Outside/In was produced this week by:

Sam Evans-Brown with help from, Maureen McMurray, Taylor Quimby, Molly Donahue, Jimmy Gutierrez, and Logan Shannon.

Many thanks this week to Rob Winder from the Aurora Public Library in Illinois and to Steve Lord with the Beacon News for helping to fill in the gaps in the story of the Fox.

If you’ve got a question for our Ask Sam hotline, give us a call! We’re always looking for rabbit holes to dive down into. Leave us a voicemail at: 1-603-223-2448. Don’t forget to leave a number so we can call you back.

Music this week from Jason Leonard, Blue Dot Sessions, Podington Bear, El Palteado, and Jahzzar. Check out the Free Music Archive for more tracks from these artists.

Our theme music is by Breakmaster Cylinder.

Outside/In is a production of New Hampshire Public Radio.